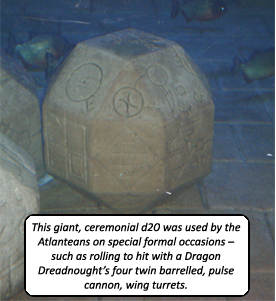

Wow, the last month has been a bit of a roller coaster ride. My crappy computer decided to give up the ghost (down), I spent a week cruising through the Bermuda triangle (way up – no Splugorth, but I did find a giant, Atlantean 20-sided die), and when I got home I found out the web host for this blog had gone out of business, erasing all my data in the process (way down)… I don’t like this ride, can I get off now please?

Wow, the last month has been a bit of a roller coaster ride. My crappy computer decided to give up the ghost (down), I spent a week cruising through the Bermuda triangle (way up – no Splugorth, but I did find a giant, Atlantean 20-sided die), and when I got home I found out the web host for this blog had gone out of business, erasing all my data in the process (way down)… I don’t like this ride, can I get off now please?

I think things are finally sorted out and I can resume regular posting again. I’ve got a brand spanking new computer thanks to the help of my more hardware savvy friends (it runs photoshop like a dream and more importantly, doesn’t sound like a jet engine taking off when you ask it to run anything more complicated than the calculator), I’ve got a new web host and I was able to reconstruct most of my old posts (I had to use text files, so unfortunately I’ve lost all the old comments and I couldn’t be bothered to recreate the scads of links – though I did remake the most important ones).

Anyway, what am I complaining about? I had a great vacation eating my weight in perfectly cooked steak, my batteries are recharged and now it’s time to make some monsters.

Resume Transmission

Tribute to Jim Roslof (1946-2011)

Old-school D&D artist Jim Roslof passed away last weekend, and given the influence early D&D art has had on my predilections, I would be negligent if I didn’t join other bloggers in paying tribute.

Wizards of the Coast have put together a thoughtful collection of memories and comments from Roslof’s friends and colleagues that is worth reading. In particular, they draw attention to his work as TSR’s art director, during which time he assembled the artistic super-team of Caldwell, Easley, Elmore, Holloway, Parkinson, and Truman. It’s an interesting story, but I’m going to focus on his work as an artist.

I have to admit up front that Roslof wasn’t my favorite artist growing up. I didn’t dislike his work, but Roslof wasn’t a name that I made a point of learning (yes, D&D artists were the first artists whose names I bothered to learn). It could have been because he often didn’t sign his works (making it harder to associate a name with him), or that his style wasn’t as immediately recognizable as an Otus or Elmore, or even that he wasn’t an artist my older brothers (who introduced me to D&D) drew my attention to. But in researching this post, going back over all the illustrations Roslof contributed to D&D products over the years, I noticed how many I remembered but had not attributed to him. When I think of D&D, it is many of Roslof’s images, still lodged in the deep recesses of my gray matter, that call out for reflection.

James Maliszewski at Grognardia has an excellent post on Roslof’s TSR cover paintings (including, in an earlier post, the iconic cover to The Keep on the Borderlands), and Mortellan at Greyhawkery showcases Roslof’s epic Thor vs. the midgard serpent illustration. Those are great pictures, but instead I wanted to focus on Roslof’s numerous black and white interior spot illustrations. These are just the kind of pictures that I mentioned earlier. They probably aren’t the illustrations that come to mind as people’s favorite, but they are immediately recognizable, and represent the visual building blocks that make up D&D.

I present in chronological order the illustrations of Jim Roslof (as usual click on the image to see it full size).

Roslof is well known for his cover painting of Queen of the Demonweb Pits, but he also did interior illustrations for the module as well, including this one depicting a yochlol and spider attacking a party of warriors. The thing I like about this picture is the focus on the party’s light source. Not only does it instantly tell the story of D&D (bringing light into the dark, unknown depths where horrible things live), it’s also a good example of game play (light sources and their durations being especially important in early D&D).

The next picture is one of my favorites that I found, although I have a hard time articulating why. It could be because The Ghost Tower of Inverness (which Roslof also painted the cover for), was one of the modules my older brother owned, and years of pouring through that booklet adds weight to all the pictures held within. It could be the play of light and shadow again. Or it could just be that the fighter pictured looks like the kind of hard bitten bad ass you wanted your character to be. He might not be superhumanly strong, but the set of his jaw, and the careful way he’s inspecting that door, give you the impression he’s seen his share of danger and bloodshed. Maybe I’m reading too much into this drawing, but I’ve always associated this guy with Nick Fury.

Roslof may have done all the illustrations for the Greek pantheon in Deities and Demigods, but since my mind had already been colonized by the Hercules cartoon those aren’t the images that stick with me – it’s his depiction of the master of the wild hunt unleashing his hounds. Everything works in this picture: the full moon, the sinister face hidden by shadow, the movement of the dogs. Just like the folk tales, when you see that on the horizon you don’t pull our your sword +1/+3 vs. shapeshifters (I don’t know why I choose that sword – I guess I always found it funny), you turn tail and run. Which, incidentally, is exactly what I did when I encountered him in an uber high level adventure a friend made for me in public school (well my characters didn’t run, they jetted away on flying carpets – uber high level remember).

As I mentioned, Roslof is most well known for the cover of The Keep on the Borderlands, but this illustration of a party attacking an owlbear graced the cover page of that module. For me this has always been the iconic image of the owlbear (I do like what Paizo did with the creature for their Kingmaker adventure path), and even though I’ve stared at this picture thousands of times, it wasn’t until today that I realized the fellow gleefully getting ready to stick the monster with his bill-hook is a halfling. I guess I was always focused on the creature (its about to rip that shield away and gut that barbarian with its razor sharp beak – or so I’ve always thought).

![]()

Finally, I wanted to mention the module Baltron’s Beacon. Not my favorite adventure (that may be because I’ve never actually played through it and hadn’t even seen it until the nineties), but its worth noting because it’s the only book where Roslof has the sole interior art credit. The illustrations are great in this module, especially the player handouts (like they did with Tomb of Horrors and Expedition to the Barrier Peaks). I wanted to end with Roslof’s only two-page spread, depicting a party fighting a group of undead lizard men. As far as I know it’s the first picture of its type that TSR published. Is Jim Roslof responsible for pioneering the ‘wall of action’ style of fantasy illustration? Who knows? But I can easily imagine this picture catching the eye of a young Wayne Reynolds when it was published in 1985.

As a post script I should also mention that I’m incredibly jealous of Jim Roslof’s cool signature. Not the coolest signature in the world (that honor goes to Bill Willingham), but infinitely hipper than my own.

The Pool of the Black One – Part One

The Pool of the Black One is Howard’s first pirate themed Conan yarn (although Conan’s past as a pirate was hinted at in The Scarlet Citadel) and establishes the rivalry between the Zingaran freebooters and the Barachan pirates. It’s also a fun blending of weird fantasy and grimy, pirate adventure – an indispensable read for anyone who’s a fan of Green Ronin’s Freeport series of adventures.

Once again though, the female character is problematic and I think I’ve finally put my finger on what bothers me about Sancha (and Natala for that matter). It’s not the ownership of women (Howard uses slavery as one of his criticisms of ‘civilization’), or that every women jumps into Conan’s bed by the end (which intimates that the only currency women have is their bodies – but this is a well established pulp adventure trope that’s continued into the action movies of today so I can hardly single Howard out for that). What bothers me is when Howard’s female characters lack any agency, any way of impacting events in the world for themselves without attaching themselves to another character. Not all his female protagonists are like that, I guess with the last two stories in a row it was just getting to me a little.

Spoiler Alert! All of these Hyborian age posts are going to be filled with spoilers. From the summary, to the monster stats they are going to ruin any surprises as to what the monster is, when they pop up in the story and how and why they are killed. You’ve been warned.

Summary

The story begins with Conan fleeing the Barachan Isles on a leaking rowboat, and then making a swim for the first ship he sees – the Wastrel, captained by the freebooter Zaporavo. There is a tense moment between the men while the captain decides what to do with the Cimmerian. Ultimately, he chooses to let Conan join the crew instead of ordering his men to cut him down. This sets into motion a series of events that will see Zaporavo lose “his ship, his command, his girl, and his life.”

After a failed hazing from the rest of the crew that leaves the offender with a snapped neck, Conan soon earns their respect with his skill as a sailor and his prodigious strength. He also attracts the eye of Zaporavo’s concubine, Sancha.

Following clues left in the legendary scrolls of Skelos, Zaporavo heads into the uncharted west, in search of a forgotten civilization and its ancient treasures. Eventually the Wastrel reaches the forgotten island and Zaporavo orders his crew to stay near the shore and gather supplies while he searches the interior alone. Conan slips into the trees after the captain, bloody business on his mind, while the rest of the crew gorges on strange, golden fruit.

Conan soon reaches his quarry, and away from the prying eyes of the crew, duels Zaporavo for the Wastrel. After slaying the Zingaran, Conan continues inland, his curiosity piqued at his former captain’s quest for treasure. There he finds a strange city peopled by tall, mute, dark skinned creatures with diabolical features. From his hiding place he sees the creatures torture the Wastrel’s cabin boy and use a magical green pool to transmute him into a tiny, petrified statue.

While Conan weighs his options, he sees that the creatures have captured Sancha, as well as the rest of the crew, who are in a drugged stupor from eating the island’s fruit. The Cimmerian draws his blade and dives into combat, buying the rest of the freebooters enough time to get to their feet and for Sancha to get them their weap ons (I guess she isn’t completely helpless). A viscous melee follows, with losses on both sides, but the invaders have the advantage of numbers, and the dark skinned giants rout.

ons (I guess she isn’t completely helpless). A viscous melee follows, with losses on both sides, but the invaders have the advantage of numbers, and the dark skinned giants rout.

Cornered in front of the pool, the leader of the creatures breaks his silence in a howl of pure hatred and sacrifices himself into the mystic green waters. The pool erupts in a volcanic geyser, unleashing a sentient wave of death in the freebooters’ direction. Grabbing Sancha, Conan and the rest of the crew make a run for the shore, barely escaping the eerie green river chasing them.

Though ragged and bereft of any bounty, Conan has won the affections of Sancha, the Wastrel and a crew eager for the plunder of more populated waters.

Black Ones

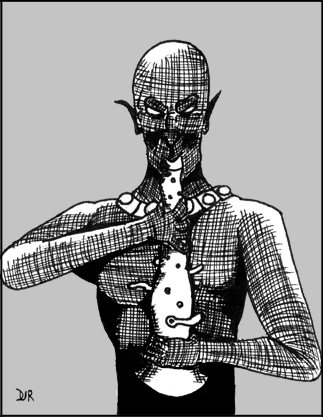

“These creatures were black and naked, made like men, but the least of them, standing upright, would have towered head and shoulders above the tall pirate. They were rangy rather than massive, but were finely formed, with no suggestion of deformity or abnormality, save as their great height was abnormal. But even at that distance Conan sensed the basic diabolism of their features.” – Robert E. Howard, The Pool of the Black One.

Nature DC 15: The creatures known as the black ones are the result of a divergent offshoot of evolution, one that branched from humanity in the dim days of prehistory. There is a marked diabolical influence in their features, and it may be that the black ones are the result of infernal tampering, many ages before the creation of the Tiefling bloodline.

The black ones live in open air cities with glass-like walls, where they enact foul rituals and pursue strange pleasures in the name of their perverse religion. It is said these cities hold ancient knowledge and treasure for those brave enough to risk the black ones’ wrath.

Nature DC 20: The black ones have no spoken language and communicate with one another telepathically. Although it is possible for them to speak with other creatures in this manner, their disdain for all other intelligent life makes the idea repulsive to them. Legend holds that the leaders of the black ones are capable of vocalizing their hatred in an obscene howl that can blast their enemies.

Encounters

It is extremely rare to find the black ones cooperating with other intelligent races. They are xenophobic, whose only contact with other humanoids is to capture victims to sacrifice in infernal rituals. However, these rituals often bind assassin imps, spined devils, and pain devils into service. Though the concept of a pet is alien to them, the black ones have been known to use behemoths as living weapons when the need arises.

Black ones guard their cities with magical traps and hazards, which often feature prominently in their religious practices and blasphemous entertainment.

cities with magical traps and hazards, which often feature prominently in their religious practices and blasphemous entertainment.

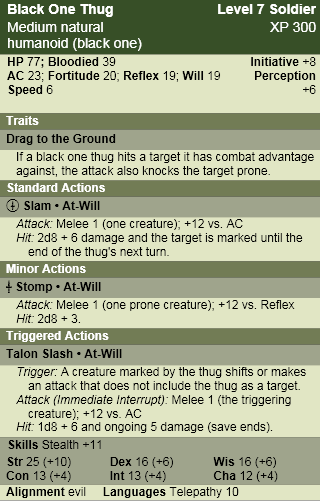

Black One Thug

“Conan knew that if he fell foul of that mass of taloned muscle and bone, there could be but one culmination. Once let them drag him down among them where they could reach him with their talons and use their greater body-weight to advantage, even his primitive ferocity would not prevail.” – Robert E. Howard, The Pool of the Black One.

Black One Thugs in Combat

Though they may appear as naked savages to the civilized eye, black one thugs are calm and collected in combat. They have no need for armor or weapons, their own bodies being sufficient to deal with the threats of their environment. When attacking, thugs select the most dangerous adversary in a group, surround, drag them to the ground, and mercilessly stomp the life out of them. Weaker foes are left alive to be captured for sacrifice and loathsome amusements.

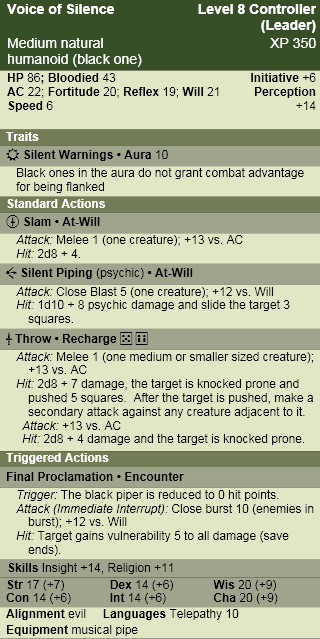

Voice of Silence

“One, squatting on his haunches before the cringing boy, held a pipe-like thing in his hand. This he set to his lips, and apparently blew, though Conan heard no sound. But the Zingaran youth heard or felt, and cringed. He quivered and writhed in agony; a regularity became evident in the twitching of his limbs, which quickly became rhythmic.” – Robert E. Howard, The Pool of the Black One.

Voice of Silence in Combat

The voice of silence is the spiritual leader of a community of black ones, presiding over the diabolic rituals around which their strange cities are organized. They focus their mental powers through their pipes, which transmit thought waves instead of sound, and can force the weak willed to dance and jig like a puppet on a string. The voice of silence uses this power in combat to force foes into dangerous hazards and isolate powerful individuals for gangs of black one thugs to overpower.

Notes:

Combined with a hazard or trap (coming soon in part 2) I think that the voice of silence and a group of black one thugs would make a good encounter. Theoretically all sorts of black ones could be created for an extended adventure into one of their cities – a fast skirmisher that can drag off captives (as happened to Sancha), or even an artillery that hurls chunks of broken glass that shatter on impact (that’s not in the story, but I think it fits and it sounds cool).

When I started this project I had intended to use the chronology of the stories as a guide to assigning levels to these creatures (and I’ll still keep that in mind), but that doesn’t always translate well into the game. Most accounts put The Pool of the Black One fairly late in Conan’s career, but the piratical adventure just didn’t seem like paragon tier material to me, so I kept it to the high heroic level. For a paragon version of these creatures I would probably (in addition to upping the damage and attack bonus) add slow (save ends) to the silent piping, daze (for 1 round) to the throw, and a bonus to damage for the thugs if more than two of them are adjacent to a character (like gnolls).

Random Encounters: Techno-Wizardry in Gamma Rifts

Techno-Wizardry is the hallmark of the Rifts game, epitomizing the setting’s mixture of high-tech and high fantasy like nothing else. There were other ‘kitchen sink’ settings that combined elements of science fiction and fantasy (as early as 1977 Dave Hargrave introduced the Techno class in the Arduin Grimoire), but Rifts was the first game that I ever played where they were so thoroughly blended.

Techno-Wizardry is the hallmark of the Rifts game, epitomizing the setting’s mixture of high-tech and high fantasy like nothing else. There were other ‘kitchen sink’ settings that combined elements of science fiction and fantasy (as early as 1977 Dave Hargrave introduced the Techno class in the Arduin Grimoire), but Rifts was the first game that I ever played where they were so thoroughly blended.

When my friends and I played Rifts in high school, we were fascinated with the concept of Techno-Wizardry, especially the rules for modifying and creating your own items (unfortunately, all we ever added to our vehicles were spoilers and bitchin’ flames on the side – we failed most of our rolls to add anything useful – go figure). Later, when I had grown dissatisfied with the system and 3e D&D came along, the clean item creation rules were something I appreciated. The Gamma World rules don’t support creating your own items (I think having to fix a vehicle or pilot a giant robot would make an awesome skill challenge), but the Omega cards are the next best thing (and some are salvageable – which simulates item creation).

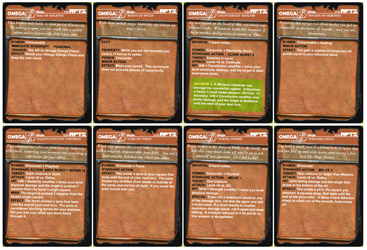

Continuing from my previous post on Omega Tech cards for a ‘Gamma Rifts’ game, I present the next 10 cards in the set of 30: the Techno-Wizard origin (just click on the picture at the bottom of the post for the full PDF). To make it easier to print out with the last 10 cards (the Magic origin), I’ve just added these to a single PDF.

I followed the same pattern as with the Magic origin cards, including 2 salvageable items, but I made sure that they occupied different item slots so there wasn’t overlap (so now we have a neck, weapon, hands, and armor item in total).

Like the last set, many of the Techno-Wizard items had a suite of powers, so I tried to distill them down to their bare essence. I also had a hard time finding consumable TW items other than psi-cola, so I created the teleport grenades out of whole cloth (grenades seem popular in the Omega cards).

One final word on Techno-Wizardry. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention Dr. Doom from Marvel comics (he is the namesake of my handle and one of the greatest villains of all time), the original Techno-Wizard. From his first appearance in Fantastic Four #5 (1962), he has always been depicted as using black magic and super science hand in hand. Given the popularity of the comic, and that it predates OD&D by nearly a decade, I’ve always wondered if the character was one of the influences on the proliferation of genre crossover in early D&D products (especially in early 3rd party books). Kevin Siembieda did work on those early Judges Guild products… who knows what the connection is (maybe Rifts was just tapping into that vibe he saw in the early RPG field)? My love of Doctor Doom tempted me to include one or two of his signature items in the set, as a tribute to the grandfather of Techno-Wizardry, but I figured I’d save it. Maybe after I finish this set of Rifts Omega cards I’ll make a small set of Marvel inspired ones (given that I’ve already mentioned my previous Rifts game included Captain America’s shield, there’s a pretty good chance of this happening).

Soon to come: the final installment of Gamma Rifts Omega Tech, Splugorth items!

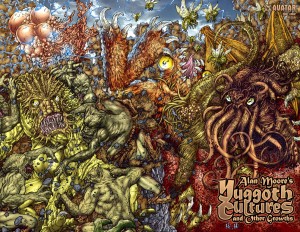

H.P. Lovecraft, Allan Moore and the Underdark

I’m pretty late to the game when it comes to Yuggoth Cultures and Other Growths, by Allan Moore. It was released as a three issue comic in 2003 by Avatar Press, and I remember seeing it in the comic stores at the time, thinking it looked very cool, and then promptly forgot all about it. The issues were collected together and released as a trade paperback in 2006, and yet again I missed out. It wasn’t until last week that I stumbled onto a reference to the comic and so I finally checked it out.

The title is a allusion to H.P. Lovecraft’s Fungi from Yuggoth, his collection of 36 sonnets (I know Lovecraft has deific status amongst gamers and can do no wrong, but to tell you the truth I’m not really a big fan of his sonnets and poetry). Moore imagined himself as taking cuttings from those fungi (stealing ideas here and there if you will – but there’s no shame in that), and culturing them to see what could be grown. It’s a great metaphor, and in general it works. It reminded me of a concept album in comic book form – you might not like every song on the record, but you dig where the band was going with it.

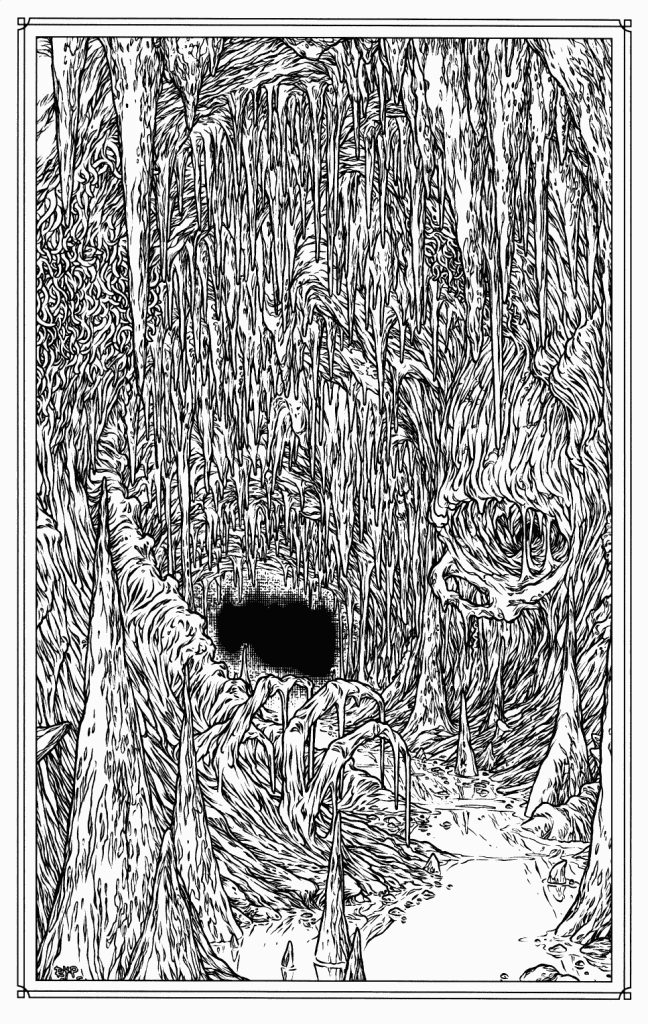

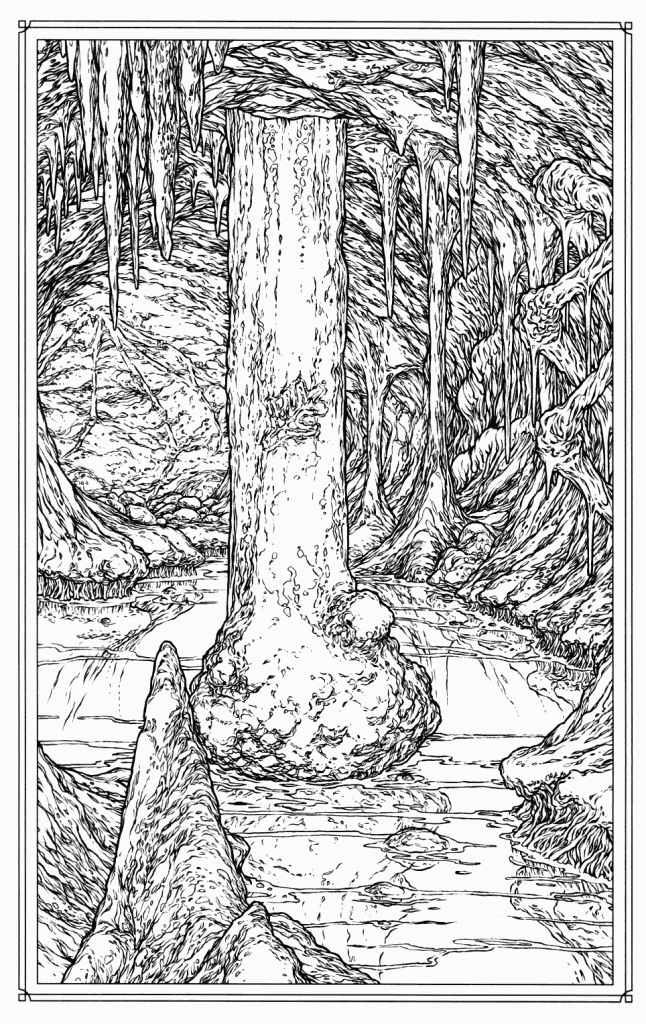

Just check Juan Jose Ryp’s wraparound cover (click on it for the full size)! The frenetic action, crazy colors and hyper detail are perfect for the madness inducing subject matter (I see Cthulhu, Nyarlathotep, a gug, a pack of ghouls, a flying polyp, and of course mi-go). As ideal as that picture is for a blog about monsters, it’s not the piece I wanted to write about.

In the same issue Ryp also illustrates Moore’s poem, Zaman’s Hill, with two pieces that are the perfect representation of the underdark, maybe even the platonic ideal of the underdark (of which all other underdarks are shadows). My penchant for hyperbole aside, when I flipped to this page I was immediately struck by the thought, ‘so that’s what the underdark looks like’ (click on the pictures to see for yourself). And that’s a bit odd, since 25 years of D&D illustrations haven’t made me think that. Considering that the underdark plays such a huge role in the imagination of D&D, there are very few visual representations of it (there are many pictures of the creatures that live there though). That’s probably because there just aren’t that many landscapes in D&D illustration in general (even though Larry Elmore was clearly a master of the style). And that makes sense. Monsters are just more interesting (I am obsessed with them) and more immediate then the places which spawn them. But a great picture can transcend that generalization and I think that Ryp’s does.

In the D&D game I currently play in, my character the Jack of Clubs and his companions are working their way through a 4e adaptation of The Night Below boxed set. We’ve fought all manner of subterranean beasts (troglodytes, trolls, grell, and a behir) and I’ve never had trouble playing out those epic struggles in my mind. But when it comes to the underdark itself I feel as though my mind’s eye has formed only a crude backdrop against which our adventures play out. These pictures have changed that. My imagination is already filling those unsettling caverns with chanting Troglodytes, the maddening psionic hum of illithid mind-song, and the glittering trails of abolethic mucous chariots. The next time someone in your game wants to know what the underdark looks like, you have your answer.

But that’s not all. Yuggoth Cultures made me realize that the fungi’s spores are still spreading, sending out shoots and occasionally, twisting back together. Many of Lovecraft’s ideas are so pervasive in popular culture they sometimes come about full circle to meet each other face to face. Way back in Dragon 324 (when you could still hold the magazine in your hands) James Jacobs had a great article on Lovecraft’s influence on D&D where he specifically mentions the Lovecraftian influence on the creation of the underdark… and that’s how a pair of pictures in a comic completely unrelated to D&D come to perfectly represent one of the game’s greatest locales. Two mutant growths, sired from the same rhizome, but cultured in entirely different mediums, turn out to be twins.

The Slithering Shadow

The Slithering Shadow features many elements that became synonymous with weird fantasy and were later incorporated into D&D: radiant gems, cultures that are near extinct thanks to their own decadence (the yuan-ti, kopru and bullywugs come to mind), and horrible monsters worshipped as gods. In fact, almost everything from the module B4 The Lost City is taken directly from this story (the desert, the adventure hook, the drug use and even the monster at the end). For these reasons the story is worth reading (and is exceedingly readable), there was just one thing that irked me – Natala, the female protagonist. Even more than the last story (where Yasmela is at least a capable ruler), Natala is a one dimensional damsel in distress. I don’t think the character ruins the story, but it’s unfortunate, since I know Howard is a better writer than that.

One last thing, I’m not really sure what ‘cosmic lust’ is, but the line is used in this story and has forever been linked to The Slithering Shadow’s monster… and just might be the inspiration for countless Japanese hentai movies.

Spoiler Alert! All of these Hyborian age posts are going to be filled with spoilers. From the summary, to the monster stats they are going to ruin any surprises as to what the monster is, when they pop up in the story and how and why they are killed. You’ve been warned.

Summary

This story takes place sometime in the middle of Conan’s career, during his tenure as a mercenary, probably after the events in Black Colossus.

Conan and Natala, a Brythunian Conan had rescued from a raided Shemitish slave market, find themselves without food and water, lost in the deserts east of Stygia. The pair are all that remains of a failed invasion of Stygia by Almuric, a rebel prince of Koth. With no hope of survival, Conan prepares to spare Natala an agonizing death by dehydration with a merciful sword stroke, but his hand is stayed by the image of a city in the distance.

The strange city is constructed from an eerie, green, glass-like material, and the main gates have been left unlocked. Inside, Natala and Conan find a guard who appears to be dead, but rouses from his torpor and attacks. Conan slays the madman, but the expected alarm isn’t raised, and no one else seems to be about on the city streets.

More exploration reveals other oddities, as well as the beautiful Stygian, Thalis. The stranger takes a liking to Conan, and enlightens the refugees over a meal. An outsider, Thalis came to the city of Xuthal as a child, and learned the city’s strange ways. Xuthal was founded by people from the east, learned philosophers whose science is able to produce food without farms, and radium gems whose touch brings lig ht to a room. But generations of leisure have led the culture to stagnate in decadence. The citizens spend most of their days and nights in a drug induced haze. They worship a horrible monster, Thog, who lives in the catacombs beneath the city and rises to feed on its sleeping inhabitants. That Xuthal’s people would accept death so fatalistically outrages Conan.

ht to a room. But generations of leisure have led the culture to stagnate in decadence. The citizens spend most of their days and nights in a drug induced haze. They worship a horrible monster, Thog, who lives in the catacombs beneath the city and rises to feed on its sleeping inhabitants. That Xuthal’s people would accept death so fatalistically outrages Conan.

Thalis desires Conan to stay, for she sees in the barbarian both a lover and a powerful tool for Xuthal’s conquest. Only the presence of Natala stands in the Stygian’s way, so Thalis kidnaps her and flees to the tunnels underneath the city via a secret passage.

Instead of leaving the bound Natala for Thog, Thalis decides to torture her captive as revenge for the wounds she suffered during the struggle.

Meanwhile, Conan works his way through the maze-like rooms and corridors of Xuthal, fighting with the roused inhabitants on the way.

By the time Conan reaches the catacombs, Thog has already devoured Thalis and is about to take his companion as well. Fearlessly, the barbarian launches into the monster, driving it away from Natala. The brutal battle sends a wounded Thog fleeing to the deepest reaches of the earth and leaves Conan beaten, torn and poisoned.

Together, Conan and Natala stumble their way into a quiet part of the city were the Brythunian is able to administer a stolen draught of golden elixir that purges the beast’s venom from Conan’s body.

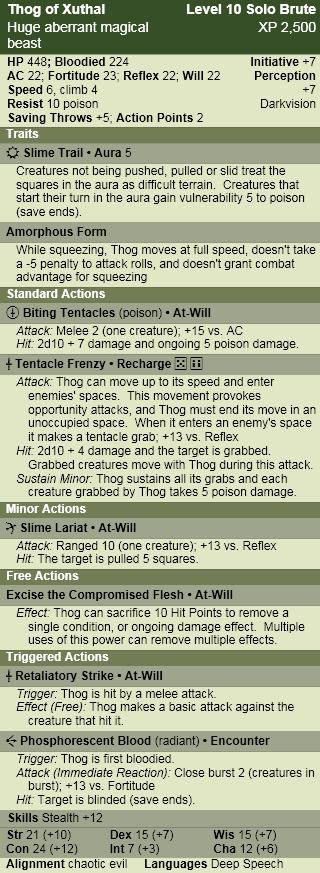

Thog of Xuthal

“It towered above him like a clinging black cloud. It seemed to flow about him in almost liquid waves, to envelop and engulf him… The thing seemed to be biting, clawing crushing, and clubbing him all at the same time. He felt fangs and talons rend his flesh; flabby cables that were yet hard as iron encircled his limbs and body, and worse than all, something like a whip of scorpions… tearing the skin and filling his veins with a poison that was like liquid fire.” – Robert E. Howard, The Slithering Shadow

Lore

Dungeoneering DC 20: In a sunken dome in the center of the legendary city of Xuthal, the monster known as Thog slumbers and is worshipped by the degenerate inhabitants as a god. The creature is so old that none can remember if it was brought to Xuthal by the city’s founders, or whether they unearthed it during the city’s construction.

Thog wakes at irregular intervals and stalks the secret corridors and catacombs of Xuthal, feeding on the sleeping inhabitants, who are content to await their doom in lotus dreams.

Thog of Xuthal in Combat

Thog is primarily motivated by hunger, and its preference for feeding on intelligent humanoids seems to suggest the creature needs more than just material nourishment to sustain its alien life. It attacks directly and fiercely, having lived so long it has forgotten the concept of death. In the unlikely event that Thog is gravely injured, it will retreat to its lair, where it is said there lies a well so deep it pierces the heart of the underdark.

Encounters

Thog spends much of its time in slumber, perhaps joining with its followers in one of the dream worlds the culture is so preoccupied with. Despite the creature’s predation, and even though they fear their god to the point of madness, the warriors of Xuthal protect the dome where the creature lairs and react violently to any incursion into the city from outsiders.

When hungry, Thog hunts alone, though creatures it shares a kinship with, like oozes and carrion crawlers, sometimes bubble up from the well in its lair and follow in Thog’s wake.

Notes:

My first solo monster! Many of the monsters Conan fights are solitary, but for some reason it seamed particularly appropriate for Thog to be a solo, especially given Howard’s description of it as “an aggregation of lethal creatures” (which mechanically is exactly what a solo creature is). I made it a level 10 challenge because I thought the monstrous god of a half-ruined city would be the perfect capstone to a series of heroic tier adventures.

I have to admit that creating a solo creature was difficult. Since each solo represents the xp of 5 normal creatures, there’s a lot expected out of a solo monster. I tried to follow Sly Flourish’s recommendations in ‘4 things every solo monster should have’, which I think is good advice, but may be a little heavy handed with the status effect protection. It’s true that a single daze or stun has a much greater impact on a solo encounter then it would in any other encounter, and could make a challenging fight into an unmemorable cakewalk, but take away these effects too indiscriminately and players will feel ripped off. What’s more, they’ll stop choosing those powers in favor of simple damage attacks, which also leads to boring combats (and nobody wants that). That’s why I chose to use the mechanic that I did. Challenge ruining effects can be ended, but at a cost (and only on the monster’s turn), and one I feel doesn’t leave the players feeling cheated. For the record I also think that Sly Flourish’s example is a good one, it’s just hard to apply some of the things he used to my case since he was working with an epic level monstrosity while I was looking to create a heroic challenge.

The Goblin

Goblins are weak pathetic creatures that spend most of their short lives throwing themselves onto adventurers’ swords. It’s hard to argue with that, especially since goblins have always occupied the lowest rung of the monster ladder (just a smidge above kobolds) across all editions of Dungeons and Dragons (and given the influence of D&D, many other rpgs and computer games as well). Take a look at David Trampier’s goblin from the 1e Monster Manual. Don’t get me wrong, I like this picture (especially that clean pen and ink style of his), and the goblin seems a little threatening, but his facial expression almost makes him look worried – and he should be, he’s about to be magic missiled to death. After about third level, goblins become a joke. So much so, it’s even used to comic effect in Neverwinter Nights: Hordes of the Underdark (the joke being that you have to be reminded that to your average zero level schmoe, a goblin is still dangerous).

Goblins are weak pathetic creatures that spend most of their short lives throwing themselves onto adventurers’ swords. It’s hard to argue with that, especially since goblins have always occupied the lowest rung of the monster ladder (just a smidge above kobolds) across all editions of Dungeons and Dragons (and given the influence of D&D, many other rpgs and computer games as well). Take a look at David Trampier’s goblin from the 1e Monster Manual. Don’t get me wrong, I like this picture (especially that clean pen and ink style of his), and the goblin seems a little threatening, but his facial expression almost makes him look worried – and he should be, he’s about to be magic missiled to death. After about third level, goblins become a joke. So much so, it’s even used to comic effect in Neverwinter Nights: Hordes of the Underdark (the joke being that you have to be reminded that to your average zero level schmoe, a goblin is still dangerous).

Trampier’s goblin is good art, but it isn’t great art. For me, great art in an rpg has to either completely inspire you (sometimes suggesting an idea, or a snippet of a narrative that compels you to fill in the blanks), or blow your mind open to a new possibility. Incredibly enough, there is a picture of a goblin that does just that. Back during the 2e days, when my friend and I encountered the picture below (click on it to see it in its full glory!), it totally changed what we thought goblins could be in the game. It wasn’t a picture of a goblin, it quickly became the goblin.

A little history. I first encountered Sam Rakeland’s painting in 2e’s The Complete Book of Humanoids (although it was first used for basic D&D’s module cover, Assault on Raven’s Ruin). I have a lot of love for this book. Back in the day, using its rules, I played a misguided lawful good minotaur, my friend played an alaghi druid, and we even ran an adventure where everyone was a mongrelman living in the sewer. None of us ever played a goblin, but that picture made us fear them again.

All grown up (relatively), there’s a lot I could say about why I like this painting: the use of oils gives it a nice tactile quality, the dynamic pose directly threatens the viewer, the colors suggest the kind of cold, dark, hard bitten cave life I imagine goblins to have… but that’s academic. The savage ferocity of the creature made an immediate and indelible impression on my teenage self. It reminded me that goblins were monsters, not just 1-1 HD things that could inflict 1-6 hit points of damage. I mean look at that thing, I think your name level paladin just cowered behind his shield and crapped in his armor… from a goblin! It made such an impression, that any time we fought goblins afterward; we always wanted to know if we were tackling any old goblin, or the goblin. We never did fight the goblin, but I can’t say my characters really regretted that.

Looking at the digital paintings that grace the electronic pages of Dragon and Dungeon now, I wonder if there’s any room in D&D for this kind of illustration anymore. These days, art directors are very concerned with maintaining a certain look for all the creatures, to help maintain visual cohesiveness and develop D&D as a brand. This approach has some clear advantages to it, the most obvious being that everyone agrees on what a goblin looks like. It educates the audience to D&D’s visual language so that every picture doesn’t have to set out what a goblin looks like. The audience knows and you can just throw goblins into an action scene and the viewer still gets it. I hope that it also ensures we never see another illustration like the one for the salamander in 2e’s Monstrous Compendium (probably my most hated D&D illustration of all time). On the downside, it also leads to illustrations that have a sameness to them (something I’ve talked about before), and flattens out individual style. Maybe it’s because I’m old and jaded, or I’m too high on nostalgia, but flipping through Dragon (I guess ‘key-ing’ is more appropriate, but that’s another rant) I haven’t seen the likes of the goblin in a long time. And that’s too bad, because I think D&D needs great art, not just good, technically adept art that makes you think ‘cool’. It needs art that’s going to blow the minds of teenagers sitting around the kitchen table and leave them remembering the images until they’re old and jaded and complaining about the pictures in the tenth edition of the game.

Then again, maybe I’m getting too worked up about a painting of some 1-1 HD canon-fodder… just try telling that to the goblin.

Notes on the Artist

Far be it for me to wax hyperbolic about the painting without mentioning the artist, who it turns out is something of a mystery (in that he doesn’t really exist).

Sam Rakeland is credited in The Complete Book of Humanoids with the painting (and his signature is pretty clear), and according to the Pen and Paper RPG Database, he also did some other covers and interior pieces for TSR in the nineties, but then his work stops. I was a little disappointed, since I was hoping to see what he had been working on lately. In my quest to find some kind of gallery or homepage, I stumbled across the Internet Speculative Fiction Database, who list Sam Rakeland as a pseudonym of artist Rick Berry. I’m not familiar with Rick Berry but it turns out he’s a prolific cover artist and I’ve seen his work on bookstore shelves for the last twenty years. You can read more about him on his page here.

I can only imagine he used a pseudonym to keep his rpg and book cover work separate… maybe he was a longtime rpg fan and had always wanted to make some material for D&D, who knows? If anyone does know more, I’d love to hear.

Of course my teenage self couldn’t help pointing out to my adult self that he recognized great art, even when it was hidden behind a false name.

Random Encounters: More Gamma Rifts

As I mentioned in my previous post, the final ingredient needed to capture the feel of Rifts earth in the Gamma World game are some magically oriented Omega Tech cards. I figured a set of 30 cards would complement the set of 40 that come with the Gamma World box and duplicate the same mix of magic and technology the ‘average’ party of adventurers in Rifts were equipped with (the mechanics of the cards have the added benefit of giving every character ‘class’ the opportunity to play with everyone else’s toys without breaking the game – meaning a robot can use a TK-machine gun and a dragon can get a cybernetic implant).

As I mentioned in my previous post, the final ingredient needed to capture the feel of Rifts earth in the Gamma World game are some magically oriented Omega Tech cards. I figured a set of 30 cards would complement the set of 40 that come with the Gamma World box and duplicate the same mix of magic and technology the ‘average’ party of adventurers in Rifts were equipped with (the mechanics of the cards have the added benefit of giving every character ‘class’ the opportunity to play with everyone else’s toys without breaking the game – meaning a robot can use a TK-machine gun and a dragon can get a cybernetic implant).

I divided the cards into 3 origins (mirroring Gamma World’s), magic, techno-wizard, and splugorth, with 10 cards each. The original cards have a salvageable card about every fifth card, so I gave each origin 2.

Presented here are the first 10 cards of the set, the magic origin (click on the picture for the full file): Bag of Holding, Boots of Speed, Counterfeit Mjolnir, Potion of Heroism, Daern’s Instant Fortress, Cube of Force, Vorpal Sword, Portable Hole, Cloak of Elvenkind, and Staff of the Magi. As you can see, these items aren’t actually from the Palladium world, but from D&D instead. I wanted to have one of the origins be made of ‘pure’ magic items, and so I went to the Palladium Fantasy game as a source first (since this is the source of these kinds of magic items in Rifts), but honestly I found most of the items were knock-offs of D&D treasures anyway. So I decided to use some of the classic magic items from the history of D&D, tempered by what I thought was cool (mjolnir) and what I needed to round out the cards (potion of heroism) – with a little help from the list in Paizo’s Classic Treasures Revisited.

The great thing about the impermanency of the Omega Tech cards is that you don’t have to worry about slowly building the party up before you can give them something cool and sexy like a Daern’s instant fortress or a vorpal sword. There’s no need for an endless stream of meat and potatoes magic items (like +1 swords) – you can head right for dessert without fear of a stomach ache (I also think this approach fits very nicely with the world of Rifts, where nothing is meat and potatoes and everything is a soul-drinking greater rune weapon).

Keep in mind that I didn’t do direct translations of these magic items, the format of the Omega Tech cards wouldn’t allow it (some of the originals of these items had suites of powers – while Omega Tech cards generally only do one thing). Instead, I focused on the general concept of each item, and in some cases gave it a Gamma World-esque twist. For example, with the bag of holding, carrying around tons of treasure isn’t an issue in the game, so I instead focused on the quirky dimensional rift aspect of the item. With the staff of the magi I thought it would be funny to make it a disposable item (with the conceit that the characters can’t figure out how to use its laundry list of powers), so I focused on the aspect that first comes to mind when you think about the iconic staff: the retributive strike.

Soon to come: the techno-wizard and splugorth items!

Black Colossus

Black Colossus is most well known for containing many of the ideas and plot points that Howard later re-used for his Conan novel The Hour of the Dragon, but is, I think, an excellent story on its own. In particular, I love the introduction. It perfectly captures the feeling and tone of something that would later become integral to D&D: exploring dangerous, ancient ruins and disarming deadly traps.

Spoiler Alert! All of these Hyborian age posts are going to be filled with spoilers. From the summary, to the monster stats they are going to ruin any surprises as to what the monster is, when they pop up in the story and how and why they are killed. You’ve been warned.

Summary

In the three-thousand year old ruins of Kuthchemes, a Zamoran master thief breaks the seal on a strangely preserved ivory dome and releases the wizard Thugra Khotan from his long slumber. Thugra assumes the identity of ‘Natohk the veiled one’ (how very Alucard of him) and raises a horde of desert nomads and elite Kushite warriors. Hungry for conquest and revenge against the Hyborian peoples that overran his kingdom so long ago, Natohk heads north, towards the kingdom of Khoraja.

Before his army reaches its first target, Natohk torments Khoraja’s ruler, the princess Yasmela, with his dark magic. Desperate, Yasmela goes to the temple of Mitra for guidance. Here, the voice of the god tells the princess that her and her people’s only hope is for her to go into the street and place her kingdom in the hands of the first man she meets there.

As fate would have it, she runs into the mercenary Conan whom s he gives control of the military. The nobles of Khoraja chafe at the idea of being led by a barbarian, but there is little choice, so the army rides out to meet Natohk’s nomads before the city is sieged.

he gives control of the military. The nobles of Khoraja chafe at the idea of being led by a barbarian, but there is little choice, so the army rides out to meet Natohk’s nomads before the city is sieged.

A titanic battle ensues, one where Conan has to face not only Natohk’s sorcery (he uses summoned mists to conceal troop movements and creates magical walls of flame), but also the arrogance and insubordination of Khoraja’s elite.

In the end, Conan’s superior tactics win the battle, but Natohk abducts Yasmela and speeds away on his demon drawn chariot with the Cimmerian in hot pursuit. The sorcerer blames the loss on his lust for the princess and intends to sacrifice her to restore his powers. Fortunately Conan arrives before he is able, hurling his sword and impaling Natohk before he can work any magic (and thus inspiring countless movies and comics where swords have been used as projectiles since).

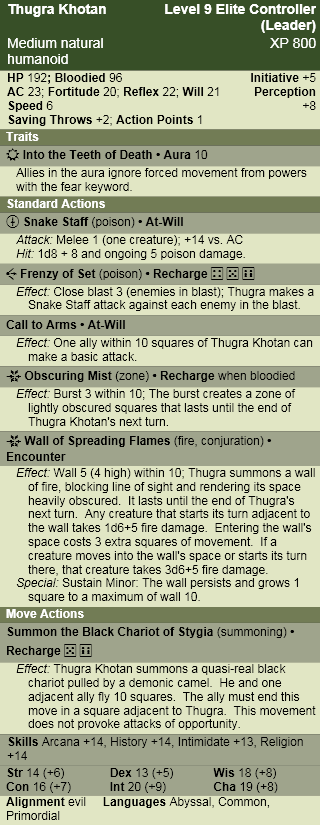

Thugra Khotan

“Natohk faced the Cimmerian – inhumanly tall and lean, clad in shimmering green silk. He tossed back his veil, and Conan looked into the features he had seen depicted on the Zugite coin… Thugra Khotan’s skull-like countenance split in a mummy-like grin.” – Robert E. Howard, Black Colossus.

Lore

Nature DC 15: Thugra Khotan is an ancient Stygian sorcerer who put himself in a deep magical slumber when the city he ruled was overrun by invading barbarians. If he were to awaken, he would surely work to restore his lost glory and take revenge against the nations descended from his enemies.

Thugra Khotan in Combat

Thugra sees himself as a great general and leader of men. He enjoys using his magical abilities to control the battlefield and execute complex strategies and ambushes. His followers obey his orders without question, for they know that Thugra’s displeasure is far worse than anything their enemies can inflict.

The Stygian has no compunctions about withdrawing from a losing battle. After all, armies can be raised, servitors can be summoned, and if need be the sorcerer can seal himself away again and wait for his foes to turn to dust.

Encounters

Thugra Khotan is a master of ritual magic, especially the summoning and binding of demons, and is always accompanied by a barlgura bodyguard. In the years since his city’s downfall, the legend of his power spawned a small but dedicated cult who is now instrumental in recruiting for the sorcerer’s army. The ranks of this horde swell with a motley assortment of bandits, mercenaries, and thugs, lured by the promise of gold, glory and bloodshed.

Most of Thugra Khotan’s targets are well acquainted with the ancient sorcerer long before his minions storm a wall or batter a gate. The Stygian is a master of psychological warfare and takes great pleasure in tormenting his adversaries with sending and other magical forms of intimidation.

Notes

I admit I chose to make Thugra level 9 purely so that he could be teamed up with a barlgura lackey – just like he was in the story (well it wasn’t exactly a barlgura, it was an ape-demon, but I think the barlgura is close enough).

I wasn’t sure if I should make him undead or not since he’s described as looking like a mummy, but I don’t think he was (he was held in stasis in the ivory dome, he had mortal lusts and he was killed by a sword through the chest… I also wanted to differentiate him from a normal D&D lich). If an undead Thugra fits your game better it’s easy enough to change and doesn’t really impact anything.

Finally, the lore check uses the Nature skill simply because that’s the 4e convention for creatures with the natural origin. I think it’s much more appropriate to use the History skill instead (that’s happened before – more and more it looks to me like the knowledge skills and monster origins aren’t lining up as smoothly as I would like in 4e).

Lost Mojo

I seemed to have lost a little of my mojo last week. I’m not really sure why, but I guess if I knew then I wouldn’t have lost it would I? Premature February blahs maybe? If that’s the case let’s hope the groundhog has some good news. In any event, it’s nothing that a little Chop Suey can’t cure and get me moving again.

I seemed to have lost a little of my mojo last week. I’m not really sure why, but I guess if I knew then I wouldn’t have lost it would I? Premature February blahs maybe? If that’s the case let’s hope the groundhog has some good news. In any event, it’s nothing that a little Chop Suey can’t cure and get me moving again.

A random thought: I wonder what kind of groundhog day type rituals would exists in a fantasy world? It would have to be something that hibernates, since waking up early from hibernation would mean a short winter. For some reason I keep coming up with owlbear (yeah I know they get a lot of hate but they’re still a classic monster to me). Obviously small villages aren’t going to send someone to poke an owlbear awake just to see if it notices its shadow, but it might put a positive spin on late winter livestock attacks… if the owlbears are out early it’s a good sign for spring and an early harvest.