Posts Tagged ‘System Neutral’

It Came From Toronto After Dark: Resolution

November 23, 2012Toronto After Dark is here, and once again I find myself skulking in the spider haunted shadows of the Bloor Cinema, madly scribbling down profane ideas birthed by the weird and wonderful sights revealed on the silver screen…

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration (if you’re in the GTA Oct. 18-26 be sure to check it out). Many of the films the festival showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

Roleplaying games helped foster an unhealthy love of monsters which hooked me at an early age to genre films, that in turn help to inform my tabletop games (in a weird kind of feedback loop). This ongoing series of articles takes these influences and mashes them together to create a strange hybrid I call It Came from the DVR (although I seem to be in the theatre more often than in front of the television, but I’m not complaining – they have better snacks).

Resolution

Resolution

When Michael receives a disturbing video of his childhood friend Chris in the throes of meth psychosis, he decides to track Chris down and give his estranged friend one last opportunity to clean up and seek treatment for his addiction. Michael finds Chris in a derelict shack in the middle of nowhere and executes his plan; he handcuffs his friend to the wall to wait for the seven days it takes for the meth to leave Chris’ system. At the end of that time Chris can decide whether or not he wants to accept rehab. In the meantime, some sinister force is toying with the friends, leaving them a series of clues that seem to tell a story. A dark mystery is about to unfold…

Intelligent, Creepy, and Funny – Like a Club Sandwich of Awesome

I find it very difficult to give Resolution a description that does the film justice. It’s creepy, but it isn’t a straight horror; it’s often hilarious but isn’t a horror comedy either; and it ties everything together with some compelling character drama… not a film that’s easily pigeon-holed. If this review seems annoyingly vague at times, that’s because Resolution is also a film that hinges on a mystery and going into some of the details risks spoiling the movie’s best parts. Indeed, Resolution is a bit like the show Lost, except the ending was actually good and looking back all the weird little components of the story made sense.

The strength to pull that feat off lies in the writing and directing duo of Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead (hard to believe they teamed up making beer commercials). The film is very smart, but never pretentiously so, and is subtle enough that it avoids the temptation to call it out to the audience and say ‘look what we did here’. It’s that subtlety that gives Resolution the re-watchability of a Memento or Inception.

I was impressed with the naturalistic dialogue, which is important since it forms the backbone of a film that spends a lot of time with two characters in a room. After the screening the filmmakers were asked if it was primarily ad-libbed, but apparently almost everything came from the script – a testament to Benson’s ability to write authentic dialogue (he could get a lot of work as a script doctor). That might not seem like a big deal, but the writing goes a long way in making the whole thing believable, which is one of the qualities that helps bring all of Resolution’s parts together.

It doesn’t hurt that the script is in the hands of the film’s two stars, Peter Cilella and Vinny Curran. The chemistry between these two guys is perfect and convincingly captures the genuine affection between old friends as well as the baggage years of addiction can burden a relationship with. In spite of each of the characters’ problems they are instantly likeable, punching up the drama of their turbulent friendship and investing the audience with concern for their well-being when things take a darker turn. They are also hilarious. Given that the film deals with meth addiction and doesn’t turn it into a joke, it doesn’t seem like there would be a lot of room for humor; surprisingly there’s quite a bit and Cilella and Curran pull it off brilliantly.

Resolution is definitely a slow burn in terms of pacing, but I never found myself getting bored (and at this point in the festival I was pretty sleep deprived, so kudos). The layers of the mystery are added on at regular enough intervals, drawing the viewer in deeper while getting progressively creepier. There is a steady buildup of intensity with the appearance of some truly memorable side characters breaking up the dialogue between Michael and Chris into digestible chunks.

Resolution is highly recommended. Watch it with a friend; because it’s the kind of film that you’re going to want to discuss with someone as soon as it ends (it’s killing me not to discuss the spoilers).

RPG Goodness

RPG Goodness

During the Q&A the filmmakers revealed that part of the reason they made Resolution, was because they were dissatisfied with traditional ‘cabin in the woods’ type horror movies. In their experience, the only people who went out into the wilderness to spend the weekend in a shack were meth heads and religious weirdoes, not frat boys and bikini models. This struck a chord with me and made me think of the kinds of NPCs that adventurers would run into as they traipse through sewers, hang out in graveyards, and camp in crumbling ruins (there is a great scene in China Mieville’s Perdido Street Station that demonstrates this well). Sure there are captured villagers to rescue and slaves to free, but, let’s face it, adventurers are pretty liminal characters who spend most of their time in places that well-adjusted and self-respecting people wouldn’t, so most of the people they’ll meet on their travels are going to come from the fringes of society. The problem is, when a random encounter is rolled or I’m planning on inserting an NPC into an adventure that isn’t central to the plot, I find my mind reaching for convenient and easy ‘stock’ characters (wily merchant, friendly barkeep, bullying guard, etc.). Resolution has some great side characters, and much like NPCs in a D&D adventure, not all of them are integral to the plot of the film, but all of them are what I like to call ‘memorable weirdoes’ – not a stock character in the lot. In order to help foster the kind of creepy atmosphere that Resolution cultivates I present the following random sampling to draw from when memorable weirdo NPCs are needed (I’ve kept them as rules neutral as possible so they can be grafted onto any NPC statblock the DM has).

Memorable Weirdoes

- Green Thumb: An attractive spellcaster has set up permanent camp near a hidden grove of yellow musk creepers. She reeks of a strange, musky perfume. Her lover was killed by one of the plants years ago and she is convinced his soul still remains in the dangerous growth of vines and flowers. She lives now only to lure others into the grove to become infected with the creeper’s seeds and be transformed into yellow musk zombies – which she believes are short-lived reincarnations of her lover. She is friendly but reserved with strangers, reading them in order to discern what deception will convince them to enter the grove unprepared.

- Grave Diggers: A group of five sullen laborers are at work with shovels and picks digging evenly spaced, deep holes in a clearing. Nearby is a mule drawn cart stacked with lacquered, darkwood coffins. The gravediggers are standoffish and tight lipped about what they are doing. Unbeknownst to them, the coffins contain a coven of staked vampires. They were paid good coin by an elderly patrician to bury the coffins and given a map to this specific location. The patrician’s family succumbed to vampirism and he couldn’t bring himself to completely destroy them. The clearing has sentimental meaning to him, and he plans to visit in the future to pay his respects.

- Mad Hermit: Amidst the chaotic wilds a lone hermit tends her incongruously orderly garden. Her clothes are threadbare but clean and her long grey hair is bound in a single braid down her back. She removed herself from civilized society many years ago to live a life without compromise or negotiation of any kind. She will not speak to the PCs (or interact in any way) unless they speak to her first. She speaks only in statements and any interaction that involves an exchange or offer of quid pro quo (which she considers a compromise) makes her progressively angrier. The hermit is a wealth of information about the area, but gleaning that treasure is difficult at best.

- The Mushroom Growers: Three wild-eyed, unkempt men with mud on their clothes and filthy hands grow hallucinogenic mushrooms in a nearby cave. They are friendly to strangers, offering to share their campfire and provisions, but become cagey and paranoid if asked what they are doing in the wilderness. They are fiercely protective of their discovery – they believe that eating the mushrooms allows them to perceive beyond the planes to the heart of reality. Normally they grow the mushrooms on the carcasses of dead animals, but if they fear their discovery is in jeopardy are not above adding a few humanoid corpses to the pile.

- The Narrator: A cloaked figure sits cross-legged in front of a large, heavy bound tome reading aloud. He appears to be narrating the story of his life, describing in flowery prose the sights and sounds of the wilderness. If the PCs approach, he includes them in his narration, even quoting their speech a few moments after it is uttered. The cloaked man will not respond to the PCs and will not stop narrating, even if threatened with violence. If attacked he does not defend himself, and uses his last breath to describe his own death. The book that he appears to be reading from is blank.

- Hunting Party: A party of young, decadent nobles crosses the PCs’ path, laughing loudly and drinking freely. They are a hunting party, complete with local guide, porter and tracking hound. They are moving cross country in pursuit of some animal, but are evasive about the nature of their prey. If the PCs seem of similar social station and like mind the nobles invite them to join in on their hunt. If not, they are rudely dismissive. Tired of hunting for bear and boar they abducted a young pickpocket from a nearby town and released him into the wild. They are eager for excitement and diversion – if the PCs agree to the hunt the nobles are willing to wager a large sum of money that their hunting party will find and kill the boy first. If the PCs antagonize them, they are quick to fight but even quicker to back down if the fight turns against them.

- The Gift: The PCs are approached by a mephit, leprechaun, or similarly devious creature. With as much sinister fanfare as it can manage, the creature offers to grant a single wish to the group. Suspicious PCs will likely suspect caveats, of which the creature is entirely forthcoming: the universe must be balanced, so a stranger will have to pay the price for whatever the PCs wish for (i.e.: if they wish for gold, someone will lose a like amount); and the bigger the wish the longer it will take the creature to complete the task (even a small wish is not instantaneous). In reality, the creature has no power to grant wishes, but loves to torment burgeoning heroes with moral dilemmas (as well as fostering strife between friends).

- The Hunted: A woman stumbles across the PCs’, her clothes and skin branch-torn. She is on the run from a horde of monsters and is desperate for help. The hounded woman is half-starved and looks as though she hasn’t slept in days. If the PCs agree to help her she describes a menagerie of fantastic creatures that have been pursuing her for the past few days. There is no sign of the monsters at first, but after the PCs bed down for the night their camp is attacked by a random assortment of creatures that explode in a shower of ectoplasm when slain. The woman’s subconscious harbours tremendous psionic power, which manifests the monsters as a latent suicidal urge every time she goes to sleep. The monsters will continue to attack every evening, until either she dies or somehow manages to come to terms with her inner demons.

It Came From Toronto After Dark: Crave

October 23, 2012Toronto After Dark is here, and once again I find myself skulking in the spider haunted shadows of the Bloor Cinema, madly scribbling down profane ideas birthed by the weird and wonderful sights revealed on the silver screen…

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration (if you’re in the GTA Oct. 18-26 be sure to check it out). Many of the films the festival showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

Roleplaying games helped foster an unhealthy love of monsters which hooked me at an early age to genre films, that in turn help to inform my tabletop games (in a weird kind of feedback loop). This ongoing series of articles takes these influences and mashes them together to create a strange hybrid I call It Came from the DVR (although I seem to be in the theatre more often than in front of the television, but I’m not complaining – they have better snacks).

Crave

Crave

In the grimy streets of Detroit, freelance crime photographer Aiden listens to his police scanner and tries to eke out a living documenting the aftermath of the city’s most violent crimes. To escape the bleak realities of his life, Aiden retreats within his own head, filling the time with elaborate revenge and power fantasies. After a chance fling with the beautiful Virginia, and a firsthand brush with crime, the barrier between Aiden’s fantasy and real lives begins to crumble.

Dark Crime Drama Takes You through the Looking Glass

Crave is the kind of film that could have flown under my radar with its understated trailer, and I’m glad it didn’t. The film has already won awards at both Fantastic Fest and Fantasia, and I hope it wins more. Crave has the potential to attract a wider audience than most genre films and, in my view, it deserves this attention.

Writer/director Charles de Lauzirika clearly infuses Aiden with a healthy dose of Travis Bickle DNA (even going so far as to have him practice comebacks in front of a mirror), but there’s more going on here than a simple tribute to Taxi Driver. There’s a black humor in Crave that sucks the audience in, convincing you to go willingly on Aiden’s journey before realizing it’s too late to turn back when things start to get crazy. The best way I can describe the relationship between these two films is to use analogy: Crave is to Taxi Driver as Brazil is to 1984 (clear as crystal, right?).

One of the things that makes this humor work so well is how easy it is to identify with Aiden. Who hasn’t used fantasy to escape the powerlessness of everyday life (given that this is an rpg blog, I’m guessing that most people reading this will agree)? The casting of comedian Josh Lawson was an excellent choice, as he brings a kind of sarcastic and awkward charm to the character that makes him instantly likeable, even when his fantasies are of the bloody variety (later in the film it’s another story, but by then it’s too late – de Lauzirika has you).

Ron Perlman also gives a standout performance as Aiden’s only friend Pete. It’s a very different role from the big bombastic characters he is usually cast as. As much as a fan as I am of Perlman’s, his subtle take on the worn down police detective was refreshing and reminded me how great an actor he is (as opposed to just being awesome).

De Lauzirika does a great job distinguishing between the violence of fantasy and real life. He contrasts the gloriously bloody, over the top action of Aiden’s mindscape with the unceremonious and bland crimes of the mundane world, giving the latter a tragic hollowness. Set against the almost post-apocalyptic backdrop of Detroit it reinforces our desire, like Aiden, to escape into fantasies of our own.

Finally, I have to commend de Lauzirika on the use of ambiguity in the film. Flipping between the real and the imagined, the viewer is often left to decide what is what on his or her own. Now, I used to be a big fan of ambiguity like this, but I’ve been burned so many times by bad storytelling (yes that’s right J.J. Abrams. I’m talking about Lost). Crave defies this trend and does ambiguity right, neither as a cop-out nor a cheat, giving the audience the tools it needs to decide what is real when Aiden cannot.

Crave is highly recommended for fans of crime thrillers and dark comedy. Keep an eye on this one; it’s got the potential to be the next word of mouth independent hit.

RPG Goodness

Crave plays with viewer perception and the boundary between fantasy and reality, subject matter that most rpg players should be intimately familiar with. The way Crave handles that boundary, by embracing ambiguity, is a lesson gamemasters can use at the table. There has always been a struggle in D&D to differentiate between player knowledge and character knowledge, particularly when it comes to things like saving throws, illusions, and the use of ‘meta’ information in game. Instead of ineffectually trying to crack down on meta-gaming (although I do discourage it), I’ve found a few techniques that, like the film, embrace the ambiguity of the boundary between player and character:

Dice: When players hear the roll of the dice from behind the DM screen, it is a hard to resist cue that something is about to happen in the game. Players won’t necessarily start taking defensive positions, but they will be a little more wary as the game proceeds. One method I used to use was to just pick up and roll a bunch of dice at random times to subvert this expectation. What I have found that works even better though, is to choose specific times when you want to increase the tension and roll a die then. Instead of subverting the meta reaction it channels it, and can be useful in subtly setting the mood.

Dice: When players hear the roll of the dice from behind the DM screen, it is a hard to resist cue that something is about to happen in the game. Players won’t necessarily start taking defensive positions, but they will be a little more wary as the game proceeds. One method I used to use was to just pick up and roll a bunch of dice at random times to subvert this expectation. What I have found that works even better though, is to choose specific times when you want to increase the tension and roll a die then. Instead of subverting the meta reaction it channels it, and can be useful in subtly setting the mood.- Mapping: Drawing a map of the dungeon (or sewer, or hedge maze or whatever) is a strange boundary crossing activity, since the characters in the game are considered to be doing it while the players outside of the game do the same. Since, for ease of play, the DM gives the players the exact dimensions of the chambers the characters are exploring, finding secret rooms or uncovering other mysterious dungeon features can become glaringly obvious when looking at the map (“hey look at that perfect room shaped space over there”). Sometimes (not always – that would be annoying) when I want to play with that ambiguity, I’ll purposefully give slightly incorrect information when describing a room (call it ‘the unreliable narrator’). It’s important to give a hidden Perception check for the character doing the mapping to notice the discrepancy – this gives an in-character replacement for uncovering secrets to out-of-character map examination (“wait a second, I only assumed this room was 20 feet long based on the size of the house, its actually only 15 – I think that back wall might hold the corpse of the murdered Countess!”).

- The Battlemat: If you play with a battlemat and miniatures (as I do), there is a strong meta-game assumption that anything you draw on the mat is terrain and anything you use a miniature to represent is a potential threat (or monster). Like rolling the dice behind your screen, you can manipulate this assumption to either lull the players into a false sense of security or increase tension and paranoia. For example, in a recent adventure my players faced off against an animated, undead throne. While its description was kind of gruesome, the players didn’t see it as a threat because I drew it out on the battlemat as a piece of furniture (and it created a great jump scare when it started to walk across the room). Likewise, whenever the party finds the long dead corpses of past adventurers (there seem to be a lot of those in adventures), I like to throw skeleton miniatures onto the mat to show their position. Rather than the players just glossing over the corpses as containers for potential loot, the whole scene suddenly becomes sinister and ominous – are those just dead bodies or are they going to sit up and attack us for disturbing their rest?

It Came From Toronto After Dark: Detention

July 16, 2012As I mentioned in an earlier post, I’ve been lurking at the Toronto After Dark film festival’s summer screenings (if you’re in the GTA don’t miss the main event, October 18-26). Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration. Most of the films the festival showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

Roleplaying games helped foster an unhealthy love of monsters, which hooked me at an early age to genre films, which in turn help to inform my tabletop games (in a weird kind of feedback loop). This ongoing series of articles takes these influences and mashes them together to create a strange hybrid I call It Came from the DVR (although I seem to be in the theatre more often than in front of the television, but I’m not complaining – they have better snacks).

Detention

Detention

It is the worst day of high school student Riley Jones’ life: her leg is broken, her IPod is stolen, dreamboat Clapton Davis has fallen for a cheerleader and she’s now officially the second most unpopular teen in the history of the school since that girl was caught having sex with the school’s stuffed mascot. On top of that, a murderous psycho dressed up as horror movie icon ‘Cinderhella’ is slashing his way through the student body. With a little help from her friends and some judicious use of time travel, Riley just might survive long enough to get to the bottom of the mystery, get out of detention and make it to the prom.

A Relentlessly Funny Work of Mad Genius

I had a criminal amount of fun watching Detention. Thankfully the rest of the audience at the screening agreed, because I was laughing so hard I was in danger of creating a Homer Simpson-esque spectacle of myself(like that’s ever stopped me). I love comedy, but it’s rare for one to connect with me as personally as Detention did. Given that the film is a crazy mash-up of teen movies, horror, and science fiction, that might seem a little strange, but there you have it. It doesn’t look like Detention will see any kind of theatrical release in Canada, but I don’t think that will stop this film from finding its audience. For nerdy, pop culture junkies of a certain age (that’s thirty somethings for those who are counting), this is the film we have been waiting for since Heathers.

Here’s the thing though. You can compare the film to the dark social commentary of Heathers, or the horror meta- humour of Scream, or the nod and a wink genre playfulness of Scott Pilgrim vs. the World – and Detention is like those movies – but it is also very unlike them at the same time. The comedy in Detention is extremely dense and extremely fast. Writer/Director Joseph Kahn works multiple levels for a machine gun pace of laughs. By the time you finish laughing at one thing, the script has already moved on to another joke, and you are also now just getting what one of the characters was referencing two minutes ago. Rather than wear the viewer down, this approach infuses the film with an infectious, manic energy.

Detention is at times incredibly clever (seriously, when was the last time you saw a movie that used The Smiths and Morrissey song titles as part of a running word-gag), and incredibly stupid in the best possible way (there’s some excellent physical comedy and a silly segue about an intergalactic space bear). A bastard child of the wiki-age, it reminded me of getting lost clicking through the links on tvtropes.org. Never mistake Detention as random, though, even if it feels chaotic. Where Kahn shines as a filmmaker is how well constructed the movie is amidst its seemingly kitchen-sink approach. There’s a strong (if convoluted) plot, and things that seem funny for one reason at the beginning take on a whole new meaning by the end (the film’s obsession with the 90’s at first seems to be a comment on the accelerated self-cannibalizing nature of pop culture but then transforms into an actual plot point once the time machine enters the story). Unexpectedly, even the time travel works in terms of Detention’s internal logic, and there’s a nice homage to Heinlein’s classic short story “-All You Zombies-“.

The best trick Kahn is able to pull off though, and his real genius, is Detention’s ability to simultaneously celebrate and critique everything it touches. The constant riffing on other films, from Breakfast Club to Back to the Future, reminds the audience why we love the filmic universe of teenagers, chasing it with a shot of nostalgia that blurs the line between remembering when we first watched that world on the screen and remembering when we lived it. At the same time Kahn also reminds us why we hate the (annoying) teenagers of today (the introduction is especially brilliant in this regard), and lets us glory in that judgement with some over the top slasher style kills.

Predicting the fickle set of circumstances that create a ‘cult classic‘ is impossible and ultimately futile. However, I’m going to be a hypocrite and say that Detention has cult classic written all over it (at the very least it’s deserving of the title). I highly recommend this film, especially for fans of Heathers and Scott Pilgrim vs. the World. Grab it when it’s released on DVD (I’ll be doing that just so I can go back through it and catch the parts I missed). But do get the friends together – otherwise you’ll feel strange laughing that hard alone.

RPG Goodness

For all its craziness, Detention reminded me of an ambitious campaign idea that’s been kicking around my head for years, one that I have always wanted to run but never had the chance – the time travel campaign. Now I’m not talking about a game where modern characters wind up fighting the Battle of Britain or hobnobbing with Romans (the Doctor Who – adventures in time and space rpg is probably the best suited game for that). I’m talking about a campaign that centres on a group of characters moving back and forth from past to present, changing things and dealing with the consequences. For example, in the original Neverwinter Nights game, you have to travel back in time to the age of the Old Ones in order to alter dungeon features to bypass an obstacle in the present. In a time travelling campaign, this sort of thing would be happening all the time.

There are many classic overarching storylines that can be used to bring a time travelling campaign together. Perhaps a Lawful Evil tyrant researches a time travelling dweomer and is using it to subtly damage the timeline in such a way that they are the undisputed lord and master of the game world in the present. Only a group of time travelling PCs has any hope of defeating such a unique threat. A different take on this would be that the characters are caught in a feud between several power groups, each with their own philosophy on how history should unfold (and if the players aren’t averse to a little inter-party conflict, one or more of those groups might be sponsoring select PCs). DMs can also use a time travelling campaign to add a twist to the tried and true ‘adventure to prevent the end of the world’ scenario. In this case the end of the world is already happening, or cannot be stopped, and the PCs must make a series of trips to the past in order to prevent the catastrophe that afflicts the present.

A time travelling campaign presents DMs with a set of unique opportunities and challenges. These guidelines should help the campaign run smoothly:

Open Temporally, Focused Geographically

Since tracking the PCs movements through time is going to be enough work for the DM, it’s a good idea to focus the campaign on a tight geographical area like a large city or mega-dungeon. This will help keep the players focused on a clear set of goals (which will discourage random wandering in the timestream), and allow the DM to easily resolve the effects of the PCs intrusion on the timeline (the wider the geographical area, the more kingdoms, political groups and deities are involved, which makes the DM’s job exponentially more difficult).

One area where you’ll be able to save on work is by re-using location maps with only minor changes. Part of the fun of a time travel campaign is getting to see different ‘versions’ of the same encounter areas in different contexts and with different opponents.

Plan Only in Broad Strokes

It’s best to think of the time travel campaign as a sandbox style game, only the PCs are exploring different periods of time instead of hexes on a map. Other than the overarching motivation for the campaign, specific planning should be left session to session to account for the sometimes unpredictable changes the PCs are going to be making (and unmaking) to history. Even more so than other campaigns, planning too far ahead when dealing with time travel can easily result in a lot of wasted work (or worse, shoehorning results out of the PCs actions).

Throw Away Canon

If your game world has a developed history, or you are playing in a published setting, accept now that time travel is going to ‘wreck’ the world. That’s the whole fun of time travel. As soon as characters are able, they are going to want to go back in time to kill D&D’s equivalent of Hitler (that could even be the goal of the entire campaign). Let them. If you are too attached to maintaining canon history, and don’t let the PCs change significant events, there is no point in running a time travel campaign.

Catastrophic, Unexpected Consequences

Of course that doesn’t mean things always work out the way the players expect. Don’t be afraid to throw a few curve balls of your own into the campaign in the vein of A Sound of Thunder (although don’t make it happen because of a crushed butterfly – it will seem a little too arbitrary and, with the mayhem that follows typical PCs, you’re going to have a lot to work with without resorting to that). If the PCs decided to assassinate the young warlord Iuz before he becomes a demigod, then have them return to a present where Vecna has risen to reclaim his spidered throne – the plot succeeding because his rival wasn’t there to stop him.

Use Time Travel Against the PCs

At some point in the campaign, the PCs should be on the receiving end of meddling time travellers. It helps to keep time travel from becoming trivial and reminds the players of the tremendous amount of power they have over the campaign world. The classic such scenario is a race against the clock to protect the PCs’ parents from a murderous time travelling villain before they are erased from history and completely disappear (see Back to the Future and Time Cop). For a slightly different challenge, have the PCs witness changes to history in real time in the present. This could play out in a climactic encounter that begins very easily, and changes as the battle progresses, with new opponents appearing, monsters increasing in power or equipment, and by having the environment altered in the enemies’ favour.

The effects of time travel can also be used as an ace in the DM’s sleeve if things get out of hand. If you’re like me and try your best to avoid ‘total party kills’ (especially as a result of a few bad rolls or over-caffeinated bad judgement), you could have a future version of the party suddenly appear to pull the PCs’ fat out of the fire. This kind of thing only works once, but it can be fun for the characters to briefly meet themselves and provides a nice in-world solution to the mulligan.

Note:

I had originally intended to include a bit of crunchy time travelling magic for Pathfinder in this article (a useful spell and a time travelling artifact), but seeing as the length of this It Came from the DVR article got a little out of hand, I’ll save it for a post later in the week. I like to think of it as evidence of the creative wellspring these films represent to DMs rather than my increasing tendency to long-windedness as I get older.

It Came From Toronto After Dark: The Pact

July 6, 2012As I mentioned in an earlier post, I’ve been lurking at the Toronto After Dark film festival’s summer screenings (if you’re in the GTA there’s still a chance to catch the second night of screenings on July 11 – Detention and V/H/S). Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration. Most of the films the festival showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

Roleplaying games helped foster an unhealthy love of monsters, which hooked me at an early age to genre films, which in turn help to inform my tabletop games (in a weird kind of feedback loop). This ongoing series of articles takes these influences and mashes them together to create a strange hybrid I call It Came from the DVR (although I seem to be in the theatre more often than in front of the television, but I’m not complaining – they have better snacks).

The Pact

The Pact

After their estranged mother’s death, Annie’s sister convinces her to return to the family home and help put the estate in order. A reluctant Annie arrives only to find her sister missing and a growing, frightening supernatural presence. Emotionally raw, with plenty of reminders of her painful childhood, Annie attempts to uncover the mystery of her sister’s disappearance.

Solidly Delivers on the Creeps

The Pact isn’t going to blow anyone’s mind with originality (and the most clever parts of the script are the things I thought were the weakest – more on that below) but it does what it does extremely well and that’s deliver an extraordinarily creepy atmosphere. It’s got all the trappings audiences have come to expect from supernatural suspense films: eerie figures moving off screen from the corner of the frame, apparitions suddenly appearing behind the protagonist, a medium who goes into paroxysms of terror when she enters the house, spirit photography and, of course, a Ouija board that moves on its own. Nothing ground-breaking. Then again, those tropes are repeated so often in the genre because they work, and writer/director Nicholas McCarthy knows how to use them effectively. For example, McCarthy does an excellent job letting the audience know that a certain door in the house is very bad, just through the use of composition, music and the reaction of Annie. It’s a great technique that is hard to pull off well (the 1963 version of The Haunting is another great example), but one that is excellent at ramping up the tension. That build-up is essential in supernatural suspense because the actual jump-out-at-you scares are sparse; you’re kept glued to the screen by the threat that something bad could happen at any minute – and McCarthy uses this to make a dated suburban bungalow seem as creepy as on old gothic manor.

McCarthy’s best ally is actress Caity Lotz in the role of Annie. Lotz’s ability to project the character’s emotional scars, without tons of script exposition, gives Annie an unexpected depth that I found engaging and sympathetic. She was also fantastic at supercharging her character with the kind of expressive fear that really sucks the audience in – you can get away with just standing there and hysterically screaming in a slasher (they’re supposed to be a bit cartoony) but suspense thrives on authentic emotion. Lotz’s reactions felt real, and I almost cheered when during her first encounter with the supernatural, she reacts by blindly lashing out at her attacker and getting the hell out of the house as fast as she possibly can. I really hope she continues to work in the horror genre.

While I was hooked into the creep fest that was the first three-quarters of this film, I felt that the last act of The Pact fell short. Much of the creepiness of the movie flows from not knowing, but the inevitable reveal of the film`s mystery robs The Pact of its scariest elements (which is the inherent trap of any mystery – not revealing anything would have been even worse). During the film’s climax when I should have been biting my nails, I almost felt kind of safe, since the sense of dread McCarthy had built up so well was completely dissipated (see more under the spoiler tag). The Pact is not alone in making this kind of mistake; I felt that to a lesser extent even Insidious suffered from this, so McCarthy’s work is at least in good company.

Despite of my complaints, The Pact has enough going for it that I recommend it to those that like the suspense horror genre and don’t need a big scary ending to enjoy a film. If you’re spending the evening in on a dark and stormy night, I think it would make a great double bill with Stir of Echoes.

SPOLER ALERT

As I mentioned previously, the big revelation in The Pact is the film’s most original moment, and is cleverly executed, but is also its weakest point. Once you realize that the supernatural force is merely trying to warn Annie, and that the real threat to those in the house is decidedly human, the film got a lot less scary. I might be in the minority, but a mundane flesh and blood killer is much less frightening to me than a haunted house with freaky ghostly manifestations where anyone who spends the night disappears without a trace.

I do have to give kudos to McCarthy for not cheating the plot though; everything about the revelation made sense without invalidating the first three quarters of the film (even the sounds made sense, an excellent little detail I really appreciated). When I see so much lazy writing on film and TV, especially where any kind of mystery is involved, it’s very refreshing to see something thought through from the beginning. I just wish it hadn’t sucked all the scariness out of the film for me.

RPG Goodness

The Pact is a great resource for DMs who want to inject some supernatural suspense into their games since it’s a veritable dictionary of the tropes of the genre – and more importantly – shows how to execute them effectively. As I mentioned in my review (with the example of the sinister door), one of the ways that McCarthy creates suspense is through the use of indirect information. Incorporating this trick into the DMs toolbox is a little counterintuitive in a game with a long history of ‘read aloud’ boxed text, but is one that can help to create a really creepy atmosphere for the right kind of adventure. Continuing with the example of the door, a similar situation at the game table might traditionally go something like this:

“The door at the end of the hall radiates palpable waves of fear and dread. As you move closer the feeling intensifies and you have to clutch your weapons tightly to keep from trembling. You press on even as every instinct screams that there is something very wrong here…”

There is nothing wrong with running an encounter this way (and it’s a pretty good in-game cue that there’s some kind of fear effect in play without being too gamey), especially if it isn’t pivotal to the adventure. However, if the door is central to solving a mystery, and if the party are going to pass by the location several times, it helps to build suspense by slowly layering indirect information to the players instead of coming right out and telling them the door is bad. Here are some examples of indirect information using the aforementioned sinister door:

- If the characters make a point of keeping the door closed, have them find it open and vice versa.

- Familiars and animal companions won’t overtly freak out, but always move in such a way that they avoid the door (a Perception check might reveal this to observant characters), and won’t cross its threshold unless forced.

- Characters walking by the door might get a sudden chill and see their breath in the cold pocket of air.

- A character who makes a moderate Knowledge (engineering) check realizes the door is in an odd location in relation to the rest of the structure and isn’t something most architects would build.

- Characters who put their ear up against the door to listen hear someone on the other side whispering things about them, but the room beyond is empty.

- Instead of their usual effect, divination spells regarding the door result in ominous automatic writing.

- Characters searching the area who succeed at a hard Perception check notice a single torn and bloody fingernail lodged between the stones of the door’s sill.

Inheriting a Haunted House

The Pact (as well as the Poltergeist series), has another great lesson for DMs – the best hauntings are by multiple spirits with distinct personalities and goals (something especially important in D&D given the way that ghosts work mechanically). This keeps the PCs on their toes, sows confusion if they assume they are dealing with a single spirit, and helps to up the creep factor by having an in-built narrative (with more than one ghost wandering around there’s got to be some kind of story there).

The easiest (and most classic) way to introduce this kind of adventure into the game is to have one of the PCs inherit property that turns out to be haunted. Alternatively, the party could be asked by an NPC contact to protect an inherited estate from wandering brigands while they put their affairs in order (and as payment they are welcome to whatever knickknacks and baubles are lying around).

To be a true haunted house, it should be the lair of at least two or more ghosts. Perhaps in life, one was murdered by the other out of jealousy and the murderer, now a ghost herself, prowls her hard won acquisition to keep intruders out and her crime a secret (and won’t rest as long as her reputation is publicly intact). The murder victim tries to warn those who spend any time in the house but as a ghost, his communication is limited to the frightful moan ability (and won’t rest until his body is retrieved from its shallow grave in the cellar). If you’ve seen The Pact, then the last quarter of the movie holds a further complication that can be recreated in a haunted house adventure (one that I think would work a lot better in a D&D adventure than it does in the film).

It Came from Toronto After Dark: The Woman

February 11, 2012These It Came from the DVR articles are going to be a little bit different. As an early Christmas present to myself, I picked up a festival pass to the Toronto After Dark film festival. So the first difference is that these are new movies, on the big screen, instead of old ones and niche programming on the small screen. The second difference is that these are going to be short. I’ve got eighteen films to see in seven days (as well as dressing up for the annual zombie walk), so I’m not going to have a whole lot of time to write, and I want post these while the blood is still fresh.

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration, but most of the films it showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

The Woman

This is a disturbing film with a bizarre premise. When a conservative, small-town family man encounters a cannibalistic feral woman in the woods, he decides to capture her and bring her home to his wife and three children so they can civilize her as a ‘family project’. Chained up in the barn, the presence of the dangerous feral woman exposes a darkness in the family that quickly erodes its whitewashed, seemingly ‘normal’, façade.

Dark Social Commentary

I should preface this review – I’ve never seen the film that precedes this one, The Offspring, but the two films are only loosely connected. The Offspring doesn’t contain any plot information critical to this film, and while the movies can be viewed as a series, The Woman also stands on its own.

The Woman cannot be easily classified. I wouldn’t call it a horror film, though there are moments when it is truly horrifying. There is humor in The Woman, but I’d hardly call it a comedy (even a black comedy). I can’t say that I enjoyed watching the film, but I also think it is a movie that is worth watching. Director Lucky McGee keeps the audience on their toes, playing with our expectations and throwing the audience a curve ball whenever you think you’ve got this strange tale sorted out.

Sean Bridgers’ portrayal of family patriarch Chris Cleek, as a sort of diabolical Ned Flanders who begins to lose control as his monolithic authority cracks, is so perfect for the film it was almost uncomfortable seeing him speak after the screening. In the Q&A, Bridgers had a very interesting view of his character when asked about the role. He said that although he was nothing like Chris Cleek, he was still able to draw on some dark, buried part of himself to fuel the role. It’s the kind of observation that I think applies to the whole film and its relationship with the audience. There is some pretty heavy violence in The Woman, including a few very uncomfortable scenes of domestic abuse and rape. Given the way that the ‘torture porn’ trend changed the landscape of horror films a decade ago, I think that McGee is confronting the audience with the ugliness of our dark psychological bits, rather than titillating them the way other horror traditions do. It’s a fine line between glorification and commentary, and everyone has a different sense of that boundary, but to me Lucky Mcgee accomplished his goals without crossing that line.

Even though her character has no real dialogue in the film, Pollyanna McIntosh gives an equally gripping performance as the titular feral woman. I was impressed with her ability to occupy the physicality of the role, and her glazed, sullen stare into the camera infuses the character with the aura of a caged animal. If Chris Cleek stands in for the controlled, oppressive violence that underlies modern society, then the feral woman reminds us of the uncontrolled brutality of the natural world. Even if the audience is cheering for the woman by the film’s climax, I’m not sure that McGee is presenting her as a viable alternative to the Chris Cleeks of the world. It’s a grim portrait of humanity that places us in a tug of war between these two poles, as savage hunters who have the choice of preying on our family units or of preying on everything not joined to us by family.

There was some controversy that came out of the Sundance festival regarding The Woman, including people walking out of screenings, which is understandable if the audience isn’t prepared for the content, but I think this has more to do with the context of Sundance than the film being too appalling to sit through. After a week of seeing decapitations, blood, and zombie cannibalism, the shock of The Woman was blunted, even if I was probably just as disturbed by it as the Sundance crowd (as far as I could tell, no one walked out of the screening at Toronto After Dark).

The Woman is recommended, but only if you’re prepared to be confronted by some alarming scenes. I can’t say that you’ll have fun watching it (and it’s about as far from being a date movie as you can possibly get), but The Woman is anything but boring and is sure to provoke a reaction.

RPG Goodness

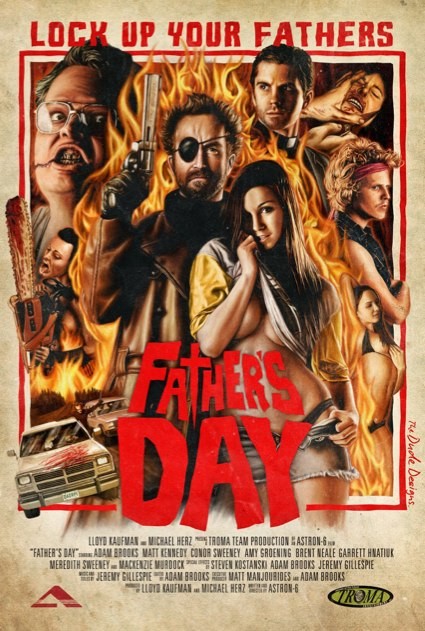

Much like Father’s Day, the subject matter of The Woman makes incorporating material from it in an rpg difficult (unless you’re making use of a disconcerting amount of the ideas in The Book of Vile Darkness). Once its more controversial elements are removed though, I think the conflict in The Woman can be viewed in D&D terms that highlight the game’s alignment system (I’ll be using the nine-pointed alignment system, since that’s my favorite, not the three alignments of BX or the five alignments of 4e).

I think that the struggle between Chris Cleek and the feral woman is a great example of how the Lawful Evil and Chaotic Evil alignments interact with one another in D&D. It would be hard to argue one of the characters was more or less evil than the other, but it’s clear that each represents a very different kind of evil, as diametrically opposed to the other as good is to evil. For me, this is why the nine-pointed alignment system (that is, an alignment in two parts – the good vs. evil axis and the law vs. chaos axis) works so well – it handles the evil against evil conflict in a way that makes sense and provides clear motivations for NPCs (which makes it useful, the litmus test for any game mechanic). It also provides clear reasons why two good aligned characters might find themselves at odds with one another or why a good aligned party might make a temporary alliance with an evil creature against a common enemy.

Although many may disagree, I’ve never found the nine-pointed alignment system restrictive. Instead, I find its two-axis approach a simple and elegant tool to encourage roleplaying by providing clear motivations for the thinking creatures of the game world. Sure it isn’t foolproof and doesn’t cover every moral quandary a PC might find herself in, but working out the finer points of ambiguous situations is one of the exciting parts of a roleplaying game.

Taking inspiration from the film, here is a sample of practical alignment complications that can be inserted into any version of D&D:

The Enemy of my Enemy is my Friend… For Now

Both Vault of the Drow and the Temple of Elemental Evil (two of my favorite classic adventures) make extensive use of this complication. Warring factions of evil creatures will use any means they have at their disposal to eliminate one another, including a temporary alliance with good aligned adventurers. As distasteful as it is, it might be in the PCs best interest. The common enemy (the most powerful house of the drow, or an evil tyrant, secure in an impregnable fortress, for example) might be too tough for the PCs to tackle on their own, or the evil creatures might possess needed intelligence in order to proceed.

Chaotic Evil creatures will promise anything to obtain the cooperation of the PCs, and if they feel they can gain from it, will attack them as soon as the job is finished. Lawful Evil creatures can be trusted to keep a bargain, but will only agree to terms that benefit them, and will constantly try to subjugate the PCs to their will.

Thanks for the Rescue, Sucker!

Just because an NPC has been imprisoned by the ‘bad guys’ doesn’t make them a ‘good guy’. Obmi, the evil dwarf from the adventure Hall of the Fire Giant King (and reappearing throughout D&D’s history) is the quintessential example of this complication. Sometimes, creatures are imprisoned by evil societies because they are so deviant or destructive that even the morally corrupt can’t stomach them.

The temptation in this scenario is to have the prisoner rampage as soon as it is freed (which is entirely appropriate in certain circumstances), but the complication works much better when the evil NPC cooperates with the PCs against his captors. Later in the campaign, let the PCs discover the horrendous crimes the freed prisoner has committed – a great adventure hook since most players will feel at least a little responsible and will be driven to stop the former prisoner.

Try not to use this complication too often or the PCs will never want to free any captives again.

What We Have Here is a Failure to Communicate

Sometimes different good aligned groups just don’t get along. The different worlds of D&D are filled with good aligned churches that are generally tolerant of one another, but still clash over major philosophical differences (which is fairly optimistic considering how well the sects of Christianity or Islam have gotten along together on Earth). If there is an established church or state religion in the area the PCs are adventuring in, they won’t appreciate the party’s cleric waltzing into their territory and performing miracles for a rival deity (or worse, actively trying to proselytize). While good aligned organizations don’t immediately resort to violence, they will definitely make things as uncomfortable as possible while they are in town. I used the church of St. Cuthbert in this manner in both the Temple of Elemental Evil adventure and its sequel. In both cases the party contained no representatives from the church and was filled with non-lawful types. Even though they wanted the same outcome (the destruction of an evil cult), the Cuthbertines viewed the adventurers as a bunch of rowdy troublemakers while the party viewed the church as a bunch of out of touch windbags trying to tell them what to do.

Rival Schools

Old-school D&D often included groups of adventurers in the wandering monster tables – a concept that Ed Greenwood greatly expanded upon in his Forgotten Realms setting (especially during the 2e era) with its predilection for rival adventuring companies. This concept hasn’t been used all that much in modern D&D (with the exception of the excellent Shackled City adventure path by Paizo), but is a complication worth revisiting. A rival adventuring company need not be evil to oppose the PCs – good aligned NPCs might pursue the same goals as the PCs (stopping an encroaching hobgoblin army, overthrowing an evil cult, or slaying a terrible dragon for example). Rather than brining the two groups together, these similarities cause tension. The rival adventuring company wants what the PCs’ want, only they want to do it first and they have no intention of sharing the spotlight (or the glory and treasure).

Good aligned rivals won’t necessarily attack the PCs, but they aren’t above sabotaging their efforts. In fact, if they are less capable, their bumbling might make things much harder for the PCs (like a failed incursion into a dragon’s lair that makes the creature extra careful and paranoid).

The Long Arm of Justice

Adventuring often means transgressing laws and taboos (like breaking and entering, tomb-robbing, and murder). That means that at some point in a campaign a group of good aligned NPCs is going to want to redress one of these transgressions. There are many remedies these groups seek, but this complication works best if the NPCs aren’t immediately violent or threaten the PCs with imprisonment (they may seek compensation, ask for a favor, or challenge the PCs to complete a gruelling ritual of atonement).

If the PCs are strongly lawful aligned, then the reverse can happen. A group of xaositects, followers of Olidammara, or tricky fey target the PCs to discredit them and take them down a notch. They use pranks, rumours, and theft to spread chaos and vex the PCs.

It Came from Toronto After Dark: The Corridor

January 30, 2012These It Came from the DVR articles are going to be a little bit different. As an early Christmas present to myself, I picked up a festival pass to the Toronto After Dark film festival. So the first difference is that these are new movies, on the big screen, instead of old ones and niche programming on the small screen. The second difference is that these are going to be short. I’ve got eighteen films to see in seven days (as well as dressing up for the annual zombie walk), so I’m not going to have a whole lot of time to write, and I want post these while the blood is still fresh.

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration, but most of the films it showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

The Corridor

This science fiction/horror story follows a group of old high school friends, drifting apart from one another, as they reunite for a weekend of bonding at an isolated cabin in the middle of winter. Here they make contact with an otherworldly force, and are unprepared for the indelible changes it leaves on their psyches. As the strange force’s influence grows, the friends find their sanity stretched beyond the breaking point and their lives in peril.

Indie Horror Done Right, the Canadian Way

The Corridor is one of those films that I wish was made more often. It reaches beyond its budget, is well written, and makes a unique interpretation of a classic trope (the cabin in the woods) by adding a genuinely Canadian voice to the genre. That’s high praise, and The Corridor deserves it.

It’s an annoying stereotype to call Canada the ‘great white north’; however, the isolation of the north is something that holds a special place in the Canadian psyche (even a Toronto boy like me knows a few lines from Robert Service’s The Cremation of Sam McGee by heart). The Corridor does a great job of capturing that feeling on film – the sense of being trapped, the cold, and the peculiar way the snow seems to absorb sound. During the Q&A after the screening, director Evan Kelly admitted what a pain it was to shoot in the snow (once you’ve kicked through a snow bank, you can’t exactly reset the scene), but I’m glad they were ambitious enough to try on the limited budget the film had, because it paid off. Visually, it sets an appropriate tone for the film, with all that oppressive whiteness pressing in on the landscape and squashing the characters. Plus, the winter is a natural obstacle to the characters simply walking away from their problems, so The Corridor avoids some of the suspension of disbelief problems that a lot of cabin in the woods movies are burdened with.

I think that The Corridor’s ‘Canadian-ness’ goes beyond its wintry setting to the nature of the fear it explores. While most (American) cabin in the woods films (like Cabin Fever, or even, if the concept of isolation is stretched, The Divide) deal with the disintegration of groups into fractured, lone individuals, the alien force in The Corridor represents overwhelming integration into a group that violently overwrites the self. I think the argument can be made that a country’s national values also hold their secret fears, and if individualism is an American ideal/fear, then I think that you can say that collectivism is our Canadian ideal/fear.

Even though it takes a while for the blood to start flowing, Kelly avoids boredom by slowly turning up the tension between the characters. While most of us don’t have to deal with mental illness in our circle of friends (another credit to the movie is the deft hand with which schizophrenic Tyler is portrayed), the grudges, hurt feelings, and lines of alliance between the characters is something that we can all relate too (especially with a group of people who grew up together). It all works to make the characters believable, which gives the violence all the more impact when it explodes onto the screen (and there’s a couple of pretty gruesome scenes in there).

Watching The Corridor reminded me of the first half of Dreamcatcher, before it takes a left turn and Morgan Freeman starts chewing on the scenery (he wasn’t the worst culprit, but he was the most unexpected one), but that doesn’t really do The Corridor justice. I think a better comparison is to H.P. Lovecraft’s short story, The Colour Out of Space. The Corridor doesn’t have any forbidden colors (or any of the trappings of the Cthulhu mythos), but the portrayal of something truly ‘other’, and the madness that force invokes, has a very Lovecraftian feel. Portraying the ‘unknowable’ is even harder on the screen than it is on the page, but I was impressed with the route that The Corridor took, walking a tight line between explaining too much and leaving things so vague as to be meaningless. By the end I felt very satisfied with the story, and although screenwriter Josh MacDonald revealed in the Q&A that this was an aspect of the film he labored over, I never once felt the mystery was disingenuous or sloppy (as I’ve said before, two of my writing pet-peeves).

There were a few scenes where I thought the acting could use a little more punch, but in general the performances were good. Likewise, there were elements that could have been more polished (for example, the character Bobcat, who was supposed to be bald, had pretty visible stubble on his head for a lot of the film), but honestly those are things that I would have completely overlooked in a lesser film. I only looked for perfection because The Corridor set the bar so high.

The Corridor is highly recommended; watch it to see what Lovecraft might look like completely removed from all the Yog-Sothothery.

RPG Goodness

In my review of The Divide, I looked at how D&D’s class system, constructed for mutual reliance, can create tension and mistrust. While The Corridor shares The Divide’s isolation and social breakdown, it uses a mind-bending alien force as its catalyst, rather than the exposure of humanity’s base nature. In D&D terms, I think The Corridor’s approach still subverts the game’s reliance on teamwork, while avoiding the fallout that comes from permanently damaging the trust that holds a party together. Actually, D&D already does this, and has since 1e’s Monster Manual. The beholder, succubus, and mind flayer (as well as many others), all have powers that subsume the will of the individual, turn adventurers against one another, and create paranoia and dissent amongst the players. The key to these monsters though, is that they also remove responsibility from the player for the actions of her character. I’ve seen some pretty horrible things happen between characters due to these kinds of monsters, all while the players were laughing and having a good time. As an example, when I ran Rifts, one of my players was mentally enslaved by a mindolar (a giant, mind controlling slug) and forced to try whatever he could to get the other characters into the monster’s lair (so they could become slaves as well). His attempts almost worked, and rather than the rest of the party being angry, the event is cited as one of the greatest moments my players had in that game.

I think that both the approach I described in my review of The Divide (limited resources, restricted movement, and mistrust), as well as the one suggested by The Corridor can be combined together to make an interesting and memorable adventure (in the form of the adventure outline I promised in the earlier review).

Castaways of the Sargasso Prison

Overview

This is an event based adventure that takes place on board the ship Wandering Grail. After a failed pirate attack leaves the Grail without a captain, the ship becomes becalmed in a treacherous region of sargasso. The PC’s must deal with dwindling supplies, power struggles between the crew, and with the monstrous creature that controls the sargasso.

Adventure Hooks

This adventure is perfect to stage while the PCs are en route to a different adventure. Perhaps they have paid for passage to distant continent, or seek adventure in the ruins of a remote island. If the PCs are mercenaries, the Captain might hire them as guards since he (rightly) fears the pirates that ply the trade routes he must cross.

Major NPCs

Captain Maraver Fleetwind (female human fighter; Lawful Neutral/Unaligned) – The ornery and unpleasant Captain Fleetwind takes an instant dislike to the party (even if she hired them). She is an unforgiving task master, and works the crew beyond their limit.

First Mate Bellray Copper (male human rogue; Neutral Evil/Evil) – On the surface Bellray is pleasant, accommodating, and completely subservient to Captain Fleetwind (while apologizing to the PCs for her behavior). In truth, Bellray is an ambitious and bitter man who will go to any lengths to take control of the Wandering Grail (including the murder of his captain).

Quartermaster Quill Urthadar (female half-elven sorcerer; Neutral/Unaligned) – Although she has the official title of Quartermaster, under the controlling leadership of Captain Fleetwind, Quill is little more than a glorified cook (not that she minds). Quill is quiet and unassuming until the supplies begin to run low; then she begins secretly hoarding food and water as a tool to control the crew. Although she justifies this as a more reasonable alternative to Bellray’s rule, she is a little too comfortable choosing who will live and who will starve.

Abbhortha (advanced kopru; Lawful Evil/Evil) – This powerful undersea creature has recently learned a ritual to calm the winds above the sargasso-choked reef it uses as a lair. It hopes to stop passing ships in order to mentally enslave their crews, spread its influence and build a new kopru empire with Abbhortha at the centre.

Event: Pirates

After a few uneventful days at sea (during which time Captain Fleetwind undoubtedly earns the party’s ire and Bellray tries to befriend them), the ship is attacked by a group of opportunistic pirates. This encounter should be difficult, not only to reinforce the dangers the sea has to offer, but also to keep the party completely occupied by the fighting. While the party is defending the ship, Bellray takes the opportunity to backstab the Captain during the confusion. Depending on the actions of the PCs, one or more may witness Bellray’s treachery (although he is exceptionally sneaky, so he tries to avoid committing the assassination within their line of sight, and even if he does should be allowed a Hide or Bluff check opposed by the PC’s Spot or Sense Motive to cover it up).

Event: Alliances

Few mourn the loss of Captain Fleetwind, and protocol dictates that command of the ship falls to First Mate Copper. The PCs may oppose this, or try and take control of the ship themselves, but it is extremely difficult to convince the rest of the crew to support them (and the ship won’t run without their support). Even revealing the assassination does little to turn the ship against Bellray (give him a +5 circumstance bonus to opposed Diplomacy checks at this point).

Bellray knows the PCs are powerful adversaries and attempts to woo them to his side, all the while working out the best way to get rid of them.

Event: Becalmed

Not long after the death of Captain Fleetwind, the Wandering Grail’s course leads it above the reef of Abbhortha, who uses a magical ritual to calm the winds and strand the boat (magical or nature oriented PCs might notice the weather is unnatural with a difficult skill check: Nature or Arcana). Rowing the ship is possible, but is made increasingly difficult due to the sargasso weed in this region (it fouls the oars and applies either a cumulative -2 to skill checks or increasingly reduces the ship’s speed until it cannot move).

During this period Bellray’s twisted nature becomes more and more apparent as he inflicts cruel and barbarous punishments for the slightest infraction. Bellwind won’t actively move against the PCs until he is sure he has the superiority of numbers on his side and can win the fight with acceptable losses. Control of the crew is best resolved as an ongoing skill challenge between the other events, or as a series of opposed Diplomacy or Intimidate checks. The breakdown of the crew into opposed factions should evolve throughout the adventure (in this conflict all sides should be aware that killing too many of the crew is virtual suicide, since the ship needs a minimum amount of people to operate).

Event: Food and Water

Although the PCs and the crew might fish for food, water reserves quickly begin to run low (and the fishing is meagre at best). This is compounded by Quill’s ongoing theft of supplies. When one of the PCs begins to suffer from the effects of thirst or starvation give them an opportunity to catch Quill stealing, find her secret cache, or have her approach the PCs with the offer of rations for loyalty. How this plays out is entirely up to the PCs. They might side with Quill to depose Bellray, or the ship might split even further, into three competing camps. As long as she controls the supplies, Quill gets a cumulative +2 circumstance bonus to opposed Diplomacy and Intimidate checks for each day the crew goes without food or water.

Keep in mind if the party has access to magic that can create edible food or drinking water it can drastically alter the outcome of this encounter.

Event: The Testing

At an appropriate time, perhaps when the Grail’s crew are at an impasse, the ship is attacked by a motley assortment of aquatic monsters (merfolk, sahuagin, a sea-lion). These beasts are the thralls of Abbhortha, and he is using them to attack the ship with the intent of thinning out the Wandering Grail’s most capable defenders.

If they are still alive, both Bellray and Quill might take this opportunity to try and consolidate their power.

Event: An Offer from the Depths

With the crew weakened by infighting and the attack by its thralls, Abbhortha begins to personally venture onto the ship at night, using its mental powers to enslave and influence lone members of the crew. The compromised crew members will act strangely (and the PCs might detect the magical influence through appropriate spell or skill), cajoling and forcing their shipmates to submit to their ‘sea god’ (and bringing them before the monster during his nightly incursions for indoctrination). If enough of the crew are converted, Abbhortha will come aboard the ship permanently – sending out his minions to capture or kill any remaining crew members. Depending on the actions of the PCs, it is entirely possible one or more will fall under Abbhortha’s sway.

If Quill is still alive during this event, she desperately wants to be on the winning side of this disaster and willingly converts to Abbhortha’s cause – even going so far as to dump her stores of food and water overboard, since she believes the new sea god Abbhortha will provide and is eager to prove her faith. Bellray (if he is still alive) on the other hand, will never submit to the sea monster’s will. The first mate would rather die fighting than give up his hard won control of the Wandering Grail. Despite his vile nature, Bellray may be the PCs’ best ally in the fight against Abbhortha.

Concluding the Adventure

If Abbhortha is prevented from enslaving a critical mass of crew members, the creature cuts its losses and cancels the ritual of becalming, waiting for a more likely target to pass through its territory. If Abbhortha is gravely injured, the beast abandons its plans (cancelling the ritual) and flees back to the inky depths.

Either Bellray or Quill, if they are in charge of the Wandering Grail by adventures end, are eager to send the PCs on their way and never see them again.

Notes:

For a higher level version of this adventure simply replace Abbhortha with an advanced aboleth.

Traditionally, kopru are listed as Chaotic Evil, but I like to think that the prehistoric empire of the kopru, before their degeneration, was Lawful Evil – a part of its racial history megalomaniacal Abbhortha would be drawn to.

It Came from Toronto After Dark: The Divide

January 20, 2012These It Came from the DVR articles are going to be a little bit different. As an early Christmas present to myself, I picked up a festival pass to the Toronto After Dark film festival. So the first difference is that these are new movies, on the big screen, instead of old ones and niche programming on the small screen. The second difference is that these are going to be short. I’ve got eighteen films to see in seven days (as well as dressing up for the annual zombie walk), so I’m not going to have a whole lot of time to write, and I want post these while the blood is still fresh.

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration, but most of the films it showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

The Divide

This bleak science-fiction drama opens with a massive attack (possibly nuclear) on New York City, as residents of a high-rise apartment flee to the basement for safety. Only a few are able to make it inside before the bomb shelter door shuts the group off from the world: married couple Eva and Sam; Delvin; single mom Marilyn and her daughter Wendi; brothers Josh, Adrien and their friend Bobby; and the building’s superintendent Mickey. What follows is the harrowing tale of the survivors as their tiny society breaks down and the worst parts of humanity come gushing to the surface.

Post-Apocalyptic Lord of the Flies

I have very mixed feelings about The Divide. It features excellent character driven drama, but suffers from very sloppy storytelling. The problems don’t ruin the strengths, but neither do the strengths redeem the problems.

Director Xavier Gens takes the viewer on a journey to uncover the heart of darkness that beats within us all and, if that was all he set out to accomplish, he succeeds. The lighting is perfect, tepidly holding back the darkness of the bomb shelter. The sets are cramped, with walls of stained, rotting concrete full of the cast off furniture Mickey has collected from former tenants – just the kind of decoration to stage the collapse of humanity. It is in this environment that Gens throws the characters of the film into crisis and against one another, in full on No Exit style, until all traces of civilization are wiped away as devastatingly as the atomic attack outside.

There are some scenes that are truly horrifying, and I found hard to watch, but that’s kind of the point (I think I would have been worried if the audience hadn’t squirmed in their seats). Gens confronts us with our most barbarous instincts as a challenge – can we face that part of ourselves and deal with it, or do we hide from it and let it destroy us? Thankfully, the director has a good instinct for timing, and sprinkles the film with a little bit of dark humor to keep the viewer from complete despair.

The Divide also has the best performances I have ever seen out of both Michael Beihn and Milo Ventimiglia (I’ve also got to mention relative unknown Michael Eklund whose descent into madness was so convincing he got an ovation during the Q&A). Gens shot the whole movie in chronological order, and forced the actors to subsist on the same diet as their characters. While I’m sure this made for a difficult production, the hardships were well worth it for the performances they elicited. Combine this with Gen’s bold decision to essentially throw out the script and let the actors evolve their own characters made for a transformation that was all the more disturbing for its organic nature.

Unfortunately, abandoning the script is also (I’m guessing), the main source of the film’s problems. Within the first fifteen minutes The Divide sets up a mystery as the focus of the plot, a mystery that is completely abandoned by the film’s midpoint and never answered or dealt with again. I kept waiting for the thread to be picked up again (even hoping for something, anything, after the credits, or in the cool comic book they gave out as swag); but it seemed like everyone in the movie had forgotten it had ever existed. Since being burned by both Lost and Battlestar Galactica, this kind of sloppy storytelling has become a pet peeve of mine and I have no patience for it. Either Gens is just messing with the audience and had no intention of pursuing the mystery (which I think is in bad faith), or he had no idea what the answers were. Either way, why put the mystery in there? I can think of a dozen ways it could have been excised and the rest of the plot kept intact. If Gens just wanted to make a character study, then that’s what he should have stuck to. Keep in mind this isn’t a sub-plot I’m getting ticked over, this is pretty much the driving force of the first third of the film.

The Divide is recommended as a disturbing post-apocalyptic version of Lord of the Flies with the caveat that you should only watch it if you can overlook the evaporating plot. If that’s not something that bothers you, The Divide has a lot to offer. Otherwise, look elsewhere to scratch that itch.

RPG Goodness

One of the cornerstones of the D&D adventuring party is teamwork. This assumption is ingrained in the mechanics of the game itself. Each class is designed to complement the others and contribute to the group (this is true of all editions of the game), with each class’ strength compensating for another class’ weakness. The fighter won’t last long without a healer, who won’t last long without someone disarming traps, who needs a magician to wipe out large groups of foes, etc. But D&D is more than a set of mechanical tools, it’s also a role-playing game and, in playing out different roles, conflict between the characters is sure to come up. At some point every DM (and some players) wants to subvert this, and The Divide lays out a strong blueprint for doing so: limited resources, restricted movement, and mistrust.