Posts Tagged ‘D&D’

It Came from Toronto After Dark: The Theatre Bizarre

December 24, 2011These It Came from the DVR articles are going to be a little bit different. As an early Christmas present to myself, I picked up a festival pass to the Toronto After Dark film festival. So the first difference is that these are new movies, on the big screen, instead of old ones and niche programming on the small screen. The second difference is that these are going to be short. I’ve got eighteen films to see in seven days (as well as dressing up for the annual zombie walk), so I’m not going to have a whole lot of time to write, and I want post these while the blood is still fresh.

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration, but most of the films it showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

The Theatre Bizarre

The Theatre Bizarre is an old-school horror anthology and pet project of some of the genre’s most recognizable names. A young woman is mysteriously drawn to a broken down old theatre where a disturbing half-man, half-puppet presents six spine-tingling tales: The Mother of Toads (Richard Stanley), where a newlywed couple encounter an ancient Lovecraftian religion dedicated to a horrible monster; I Love You (Buddy Giovinazzo), a meditation on a relationship poisoned by mistrust and obsession; Wet Dreams (Tom Savini), features an unfaithful husband getting his just deserts in this reality and others; The Accident (Douglas Buck), a glimpse of the life and death horror of the mundane world as told to a child; Vision Stains (Karim Hussain), follows a junkie who chronicles the memories of her murder victims, which she re-lives after injecting their vitreous fluid directly into her eye; and Sweets (David Gregory), where a couple find that their relationship based on binge eating takes a strange turn.

Horror Buffet – Take What You Like and Leave the Rest

I’m not sure why anthology films have fallen out of fashion in North America, but growing up Creepshow, Creepshow 2, and Tales from the Darkside: the movie had a big impact on my imagination, and I miss the format (I even saw Creepshow 2 in the theatre – which not only dates me but also how long it’s been since an anthology movie got wide release). Because of that, I was looking forward to the Theatre Bizarre and only slightly concerned that the movie’s six stories would be too short for the filmmakers to do anything with. While I didn’t enjoy every tale, I liked the majority. I suspect most of the crowd felt the same, though I’m sure everyone had different opinions on which segments they liked and disliked – that, I think, is the strength of the anthology structure.

The other strength of anthologies is that they are the filmic equivalent to short stories, a format perfectly suited to the horror genre (and not just because it’s my favorite way to read horror stories – I love Clive Barker’s Books of Blood and Stephen King’s Night Shift is the book that got me interested in horror). I like to think that horror is about infecting someone with a disruptive idea, an idea that hides in their brain and won’t go away (often remembered at such inopportune times as walking down an empty street in the middle of the night). Short stories are such an effective delivery for horror because they deal with a single idea, stripped of any distraction, and freed from the need to dilute it over the course of an entire novel (or film). During the question period after the screening, it was nice to hear the filmmakers were given complete creative freedom over their segments, and I think each of them took advantage of the format to tell focused short stories (even the ones I wasn’t crazy about).

The wraparound story (featuring genre perennial Udo Kier) that ties the segments together does its job of moving from one section to the next smoothly. It doesn’t stand out, but I think that’s the point, as it would distract from the other stories.

The Mother of Toads is a great little monster story. The set-up is creepy (with an excellent performance by Catriona MacCall as the old woman), the monster looks fantastic, and the ending pays off. That it has a liberal helping of Lovecraft mythos is just icing on the cake.

I Love You is also a strong entry. It reminded me of the clever storytelling of the Twilight Zone – only with good acting, and modern dramatic sensibility (no offense to Rod Serling – it will always be a classic).

I didn’t care for Wet Dreams. Maybe it was the similarity in theme to the superior I Love You that makes it seem flat in comparison, but I felt Tom Savini’s entry lacked any emotional depth and came off cheesy (it looked good though). If I Love You is a great chapter in the Twilight Zone, Wet Dreams is a bad episode from Tales from the Crypt (which is why I’m sure some people will love it).

The Accident really stands out from the crowd for its complete rejection of any supernatural or traditional horror elements (and for that audacity alone this might be my favorite segment). The story is so simple, but so effective at reminding the viewer that we tell scary stories to distract ourselves from the terror of everyday life. I’m sure I wasn’t the only one in the audience who had painful images from childhood come bubbling back to the surface after watching this.

Vision Stains has one of those ideas at its heart that you absolutely want to steal, and completely lived up to its promise (the double edged sword of any great idea). Its narrative, about our obsession to know everything, hit home (as I’m sure it will for others in our Google and Wikipedia age). Vision Stains also boasts some of the gnarliest (and well done) eye injuries I’ve seen, so fair warning to the squeamish (and those who have a hard time watching others put in contact lenses).

I’m on the fence about Sweets. On the one hand the vivid, surreal feel of the segment is fantastic. On the other, I felt the impact of the ending was blunted by relying on a series of gross-outs. At this point in the day of screenings, I was starving, and in spite of my hunger Sweets had enough of an effect on me that I didn’t make a trip to the concession stand, so in the final analysis I guess I have to judge David Gregory’s work a success.

The Theatre Bizarre is recommended (especially for those who remember films like Creepshow and Tales from the Darkside with fondness). The film’s discreet segments make it perfect to throw on next Halloween, and watch between bouts of handing out candy. I can’t guarantee you’ll enjoy every part (or even that you’ll like the ones that I did), but there’s enough quality storytelling in the Theatre Bizarre that it hits more than it misses (and the segments are short enough you won’t mind sitting through the misses).

RPG Goodness

Watching Vision Stains, I couldn’t help but think the whole eye-injection thing would make a very creepy way to cast the spell speak with dead in a dark steampunk game or a twisted version of Eberron. With much of D&D fandom, myself included, showing a renewed interest in the game’s pulp fiction/sword and sorcery roots, there’s a general feeling that D&D’s magic system (of any edition) is too ‘high fantasy’ to gel with that approach. Rather than scrap the whole magic system, I think Vision Stains demonstrates that something as simple as cosmetic changes to the way that spells are cast (the somatic and material components in 2e and 3e) can completely alter the tenor of even the most innocuous magical effect (in the case of the film, humble information gathering). The following are a small sample of common spells altered to add an element of the dangerous, weird and horrific to magic in D&D games:

Bear’s Endurance, Bull’s Strength, Cat’s Grace, Eagle’s Splendor, Fox’s Cunning, Owl’s Wisdom – the recipient of the spell consumes a pickled organ (usually a heart to improve physical attributes or a pineal gland for mental attributes) belonging to a creature with a higher score in the appropriate statistic. This makes finding suitable component sources difficult for individuals who want to improve an already fantastically high score.

Cure Wounds – the wounds of the living are healed by grafting chunks of flesh from the bodies of the fallen. Discoloration due to a difference in species between donor and recipient fade after twenty-four hours.

Detect Magic and Identify – the caster enters a deep trance through the use of an inhaled or injected drug. This drug is harvested in an unsavory manner or from an unpalatable source such as illithid brain juice or powdered grave mushrooms.

Floating Disk – the material focus for this spell is a metal or wooden lip disc that must be worn for the spell to function.

This wouldn’t be much of a monster focused blog if I didn’t mention the Mother of Toads again. While watching the film it struck me that the creature in Richard Stanley’s segment was a lot like a D&D bullywug, and a Cthulhu mythos connection to this monster (which I’ve always felt was under-appreciated) would go a long way in redeeming its appearance on the Dungeons and Dragons cartoon (where they were lamely defeated by giving them giant flies to eat). Well, after a little research, it turns out there is a connection (that’s actually a little tangled back and forth). The Mother of Toads is inspired by a Clark Ashton Smith story of the same name, written as a part of his Averoigne cycle, a collection of tales that also inspired the classic module Castle Amber. Just as likely, bullywugs could have been inspired by Clark Ashton Smith’s more famous addition to the Cthulhu mythos, the frog-like Tsathoggua (the man liked his frog beasties).

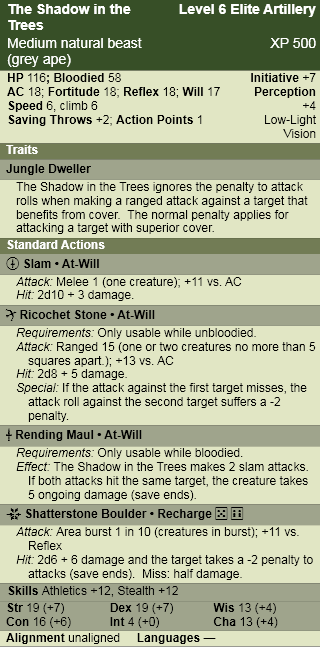

Either or, the best way to make the connection concrete is to immortalize the mother of toads in monster form…

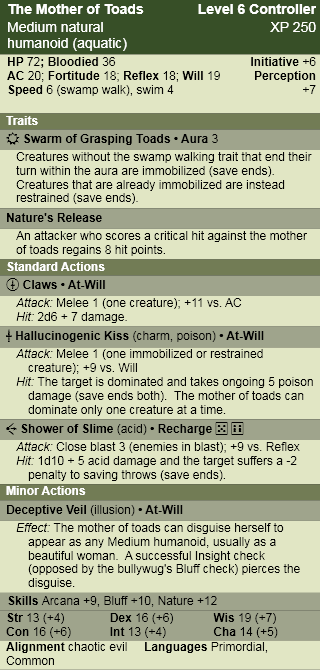

The Mother of Toads

“Pierre awoke in the ashy dawn… Sick and confused, he sought vainly to remember where he was or what he had done. Then, turning a little, he saw beside him on the couch a thing that was like some impossible monster of ill dreams; a toadlike form, large as a fat woman. Its limbs were somehow like a woman’s arms and legs. Its pale, warty body pressed and bulged against him, and he felt the rounded softness of something that resembled a breast.” – Clark Ashton Smith, Mother of Toads.

Lore

Nature DC 10: The mother of toads is an agent of the fetid and swampy primordials that created the bullywugs, and is worshipped as a deity by all the batrachian creatures of the marsh.

Nature DC 15: Some rumors hold that the mother of toads is incredibly ancient, the first bullywug hatched from the original god-egg that spawned the race before it could breed true. Since she is unable to reproduce with other bullywugs, the mother of toads mates with degenerate cultists and human captives.

The Mother of Toads in Combat

The mother of toads takes perverse pleasure in using illusions to lure unwary travelers into her embrace while her pets and servants hide nearby. In the event of combat she reveals her true, disgusting form, immobilizing foes with swarms of frogs, and weakening them with a spray of secreted slime. The mother of toads usually chooses the strongest and most virile looking male to control with her hallucinogenic saliva – committing unspeakable acts with the mind controlled slave once his companions have been eaten.

Encounters

The mother of toads dwells in a rustic cottage at the edge of a wild and dangerous swamp where she poses as a friendly herbalist and healer. The swamp is littered with weird and sinister primordial idols from the time before the dawn war. The mother of toads children (bullywugs, as well as giant frogs and toads) are never far off and always heed her commands.

It Came from Toronto After Dark: Love

December 24, 2011These It Came from the DVR articles are going to be a little bit different. As an early Christmas present to myself, I picked up a festival pass to the Toronto After Dark film festival. So the first difference is that these are new movies, on the big screen, instead of old ones and niche programming on the small screen. The second difference is that these are going to be short. I’ve got eighteen films to see in seven days (as well as dressing up for the annual zombie walk), so I’m not going to have a whole lot of time to write, and I want post these while the blood is still fresh.

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration, but most of the films it showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

Love

Set in the near future, this film focuses on the life of astronaut Lee Miller during a solo mission on board the International Space Station. Shortly after his arrival, something goes terribly wrong on the planet below and all communication stops. Alone, Miller must deal with crushing loneliness and the dangers of the aging space station. Hidden amongst the junk of previous crews, Miller finds an old journal written during the American civil war that hints at a profound secret. As the astronaut begins to lose his mind, fantasy, reality, and the mystery of the journal begin to bleed into one another.

Visually Stunning, Emotionally Charged

Love is not a film people are going to feel ambivalent about. Standing in line for the movie that followed the screening, it was apparent that festival goers who had just seen Love had very strong opinions about it. I enjoyed Love immensely, and I’m not sure if it was the lack of sleep this far into the festival, but the movie had a pretty big emotional impact on me as well.

Before I go into Love’s merits, I think a good litmus test on whether you are going to hate this film depends on what you feel about 2001: A Space Odyssey – If you dug the second half of that movie (when Dave is alone on the ship, up to and including the funky space warp with the monolith), then I think that Love is for you. But 2001 isn’t for everybody, and neither is Love. I should also confess that I like the movie Solaris, so if that throws my judgment into question, I’ll understand.

Before making Love, writer and director William Eubank worked as a cinematographer, and it shows. Love is absolutely beautifully shot. There were moments, especially the civil war battle scenes, that I can honestly say are some of the best looking filmmaking I have ever seen. After the screening Eubank announced that the film is being distributed on iTunes, and I’m glad it will reach a wider audience, but it also pains me to think it won’t get a proper theatrical release because I’m not sure you’ll be able to see the depth of detail on the small screen. One scene in particular stands out in this regard – an amazing slow motion shot of a charging soldier where you can see the individual particles of dust being blown off his uniform by the shockwave of a nearby exploding mortar shell. Amazing stuff.

Contrasted with the wide open, vividly colored civil war and fantasy scenes, Eubank creates a space station whose muted colors and oppressive atmosphere are cranked up to a Das Boot level of claustrophobia. Actor Gunner Wright takes full advantage of this in his role as the astronaut (which is good since he’s on screen for the main chunk of the film). His performance pulled me into Miller’s world, and aside from a few hiccups (he’s been in space how long?), kept me there for the full hour and a half.

The most incredible thing about Love though, and I still find it a little hard to believe given how good it looks (have I gushed enough yet?), is that the entire thing was shot in the back of Eubank’s parents’ ranch, with all the sets built by Eubanks in his spare time. Even if you hate the movie (and I’ll admit there were quite a few haters in the audience), you have to be impressed by what the filmmaker was able to accomplish with the little he had. Did I also mention it was shot with borrowed cameras?

I referenced 2001 earlier, and the DNA of Kubrick’s heritage is strongly manifest in Love. There will always be cries of rip-off when a film wears it inspiration on its sleeve like Love does, but I feel it just manages to steer shy of being derivative and say something new. Love shares many of 2001’s themes (isolation, madness, the meaning of humanity), as well as some superficial elements (most of which are spoilers), but goes about exploring them on a tangential course. Ultimately, Eubanks has very different things to say about people than Kubrick does, and each film elicits a very distinct emotional response.

Love is recommended, especially for fans of 2001 who want to see a different reading of similar themes. Even if you aren’t a fan of that kind of film, I recommend tracking down the civil war scenes and watching them on as large a screen as you possibly can.

RPG Goodness

Unlike most stories, which use clues or revelation to propel the plot, the driving force of Love is the absence of information (communication with earth ceases). It might be counterintuitive, but I think it’s a technique that can be applied to rpgs both to foreshadow future adventures and to inject a little verisimilitude into the game world.

Beginning with the rumor table in the venerable Keep on the Borderlands (Bree-Yark means ‘I surrender’ in goblin language), and evolving into skill checks to gather information (or Streetwise or Conspiracy), D&D adventures have a long history of enticing players to progress to the next stage of the plot with packets of information. I think that the absence of information can be just as motivating to players, driving them to seek out the answers.

As an example, instead of introducing the module Against the Giants with the Grand Duke informing the players that an alliance of giants has overrun the western portion of his dominion, pique their curiosity by telling them the grand duchy hasn’t heard from any of the villages bordering the Crystalmist Mountains in weeks. The PCs, dispatched to find what has happened, can find evidence of giant attacks and as the adventure progresses, will come to realize the attacks are the result of a sinister group of masterminds organizing the disparate races of giantkind. By starting with nothing, and uncovering the facts of the mystery themselves, the PCs ‘own’ the information, and are much more motivated to advance the plot of the adventure than if they felt the mystery was someone else’s (and therefore someone else’s problem – sorry Grand Duke, not interested).

Providing the players with gaps of missing information also works well when introduced into the campaign in the middle of a different adventure. That way the mystery stays at the back of the players’ heads while they deal with more pressing matters, and when the issue comes up again later in the game (or escalates) it seems more organic and less like a video-game series of quests to tick off (thank-you for collecting eighteen squirrel tails, now I need a letter delivered…). The absence of information can sometimes be just as important as a rich background for making the game world come alive.

Love also tackles the theme of isolation, which is difficult to apply to rpgs in an existential sense, but when thought of more practically, is a powerful tool in the DM’s arsenal (so powerful in fact, that it should be used sparingly or it will grow old very fast). The old adage, ‘don’t split the party’ is true for a reason, and nothing panics a group of adventurers like being isolated against their will. Pits (the Dungeon Master’s Guide has the standard example but my favorite is the pivoting floor and wall from Pyramid of Shadows), portcullises (from Dungeon Master’s Guide II) and conjured walls (just add the wizard class template to a monster and choose wall of fire, wall of ice or the forcecage power) are all excellent devices to separate members of the party from one another, especially when combined with a combat encounter. If you are feeling extra devious, use this tactic while toying with the players’ impatience – stagger the combat encounter so the panicking players waste their most powerful abilities and resources on weaker creatures before the ‘big bad’ shows up (to reiterate, use sparingly if you don’t want to be pelted with dice).

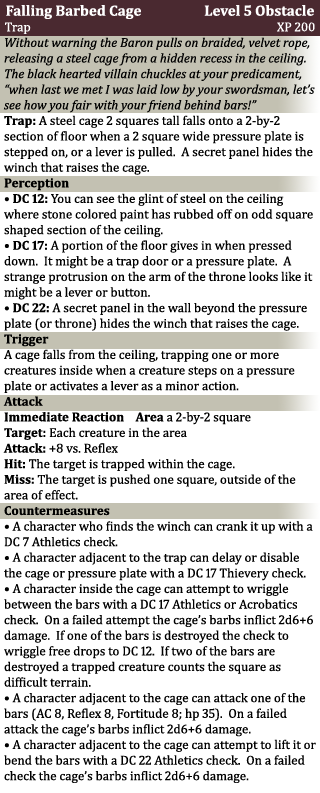

The falling cage is a staple of evil throne rooms, does an excellent job of separating the party without separating them from the action, and I have yet to see one in a 4e adventure. For that reason I present my own take on this classic trap.

Falling Barbed Cage

This trap works best in a combat encounter where the pressure plate is located between the party and a controller or artillery type monster, optimally along an obvious path of least resistance. Alternatively, you can give control of the trap to one of the monsters, who waits until the characters are in position to activate the trap.

The falling barbed cage doesn’t inflict very much damage on its own, but is excellent at occupying and pinning down strikers and defenders that rush forward to attack soft targets.

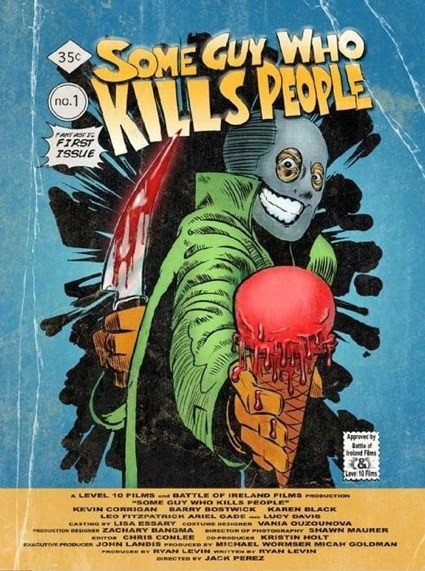

It Came from Toronto After Dark: Some Guy Who Kills People

December 16, 2011These It Came from the DVR articles are going to be a little bit different. As an early Christmas present to myself, I picked up a festival pass to the Toronto After Dark film festival. So the first difference is that these are new movies, on the big screen, instead of old ones and niche programming on the small screen. The second difference is that these are going to be short. I’ve got eighteen films to see in seven days (as well as dressing up for the annual zombie walk), so I’m not going to have a whole lot of time to write, and I want post these while the blood is still fresh.

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration, but most of the films it showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

Some Guy Who Kills People

In this dark comedy, all of Ken Boyd’s problems can be traced back to the traumatic bullying he endured during high school. It drove him to attempt suicide, which led to a stint in a mental hospital and now the only work he can get is a humiliating job at an ice cream parlour. Living with his bitter and sarcastic mother, Ken trudges along the rut of his life… but everything changes when his estranged teenage daughter comes to stay with him and Ken’s tormenters start dropping like flies.

Dark, Sweet, and Funny

I expected Some Guy Who Kills People to be dark (it pretty much spells things out in the title), and funny (the trailer was hilarious) – and the film delivers. What I didn’t expect was how sweet Some Guy Who Kills People is. It’s rare to find a black comedy without a cynical bone in its body, but this film makes it work. Maybe the murder and revenge keep the movie from descending into corniness and the sweetness keeps it from sliding into ironic despair. I’m not sure, but it’s a nice balance. You could call it ‘dark chocolate for the funny bone’ (eat your heart out Chicken Soup for the Soul!).

That balance that I mentioned takes great acting to pull off, and Some Guy could have been a disaster without it. Kevin Corrigan is wonderful as the painfully awkward Ken, but isn’t so unreachable that you don’t feel sympathy for the guy when he has to cater the birthday party of one of the bullies dressed as a giant foam rubber ice-cream cone (and if it wasn’t painful it wouldn’t be nearly as funny). Karen Black also does a good job as Ken’s harpy mother with a heart of gold (if you watch Burn Notice imagine Michael Weston’s mom, but instead of growing up to be a super-spy he had a dead-end job and still lived at home). Barry Bostwick is hilarious as the bumbling local Sherriff (although bumbling isn’t really the right word – more like ridiculous) – anchoring much of the movie’s humour with straight-faced certainty and absolute deadpan delivery. Holding her own amongst these veteran actors (shining even) is Ariel Gade as Ken’s young daughter. I think I might even go so far as to say that her sincere performance, filled with spunky optimism, is the heart and soul of this film. I see from her IMDB page that she’s been in a few movies I’ve watched (Dark Water, and Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem), but I have no memory of her (sorry). If Some Guy gets wide release, her relative anonymity will change, because it will catapult Ariel Gade’s career like Little Miss Sunshine did for Abigail Breslin.

I’ve focused on the lighter elements (because they really stand out in a festival like Toronto After Dark) but it isn’t all gumdrops and lollipops, there’s also murder and death. The kills are creative and funny, though I would have liked them to be a little bloodier (not Saw level violence mind you, but a little absurd, over the top arterial spray would have added something).

Some Guy Who Kills People is recommended. It’s a nerd fairy tale; watch it when life’s got you down and you want a revenge fantasy with your happily ever after.

SPOILER ALERT

I really only have one criticism of the film, but it’s wrapped up in a spoiler so I wanted to put it down here. I won’t give too much away, but towards the end of the movie is a big plot twist (which is a spoiler if you’re looking for it the whole time). At the end of the day it felt sort of awkward, as the mystery is one of those reveals, which is full of information that isn’t given to the audience prior to the twist. I also felt it undermined what the filmmakers were doing with one of the main characters, since you cheer for him in spite (maybe because) of the murders. It doesn’t ruin the movie; it just felt like they pulled their punch a little at the end.

RPG Goodness

Although the murders in Some Guy Who Kills People are funny (and the victims are unrepentant douchebags), they are also unequivocally ‘bad’ (as in ‘not something a good person would do’). Watching the film with rpgs on the brain, I couldn’t help but think that the actions of the serial killer in Some Guy would not be out of place on the tabletop, and might not even be considered all that bad depending on the context they were committed within. If the bullies happened to be a cabal of evil wizards in a dark tower, the PCs wouldn’t think twice about breaking into their home and slaughtering them in cold blood. If though, like in the film, the bullies were just a bunch of 0-level commoners from town, things should be different.

The context of the PCs actions in both scenarios is informed not only by the morality of their alignment, but also by what I like to call the ‘frontier mentality’ (since it plays out very much like a western). Things are dangerous in the wastelands and dungeons outside of civilization and the stakes are life and death. Though mercy is expected of the noble, hostility is most often met with brutal violence. On the other hand, once back behind the walls of society (‘in town’), adventurers need to heed the law and start acting civilized again. The frontier mentality is something I like to play with in my games, by placing NPCs in town that I know will get the goat of the players, just to see if they can keep their swords in their sheaths (hey, DMs are allowed to have fun too). I think using the scenario of the film (the PCs running into childhood bullies in town) would make for an exciting and tense encounter, especially if the bullies pose no physical threat (can the PCs resist the temptation?).

The arrival of Ken’s teen daughter in the film got me thinking – what would the PCs do if they had to bring a young dependant along with them on their adventures? Instead of being a hassle, what if it was actually a reward? The appearance of a young companion or sidekick that the hero is responsible for is a staple not just of comedies but also of action/adventure movies and comic books. In spite of this, the only similar situation I can recall in my own games was when we made use of a table in 2e’s Complete Book of Bards– if a bard’s fame score was high enough a number of special events could occur, one of them being an obsessive 0-level fan that followed the character into dangerous situations. While the crazed fan proved to be a lot of fun, he was hardly a benefit to the party. I think that sidekicks can be both a boon and a liability (as they are in comics and films), so here I present guidelines for ward characters in D&D.

Ward Characters in D&D

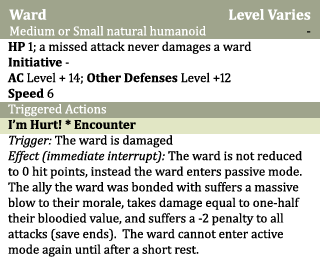

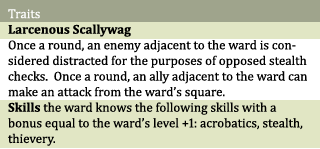

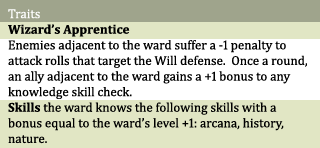

After the hobgoblins of the red hand destroy your village, you must escort your feisty nephew to safety, out of the reach of the war. Your renown has brought you to the attention of the indulgent Baron of the Nentir Vale, who volunteers you to take his headstrong daughter with you on your next adventure. In order to fulfill your obligations to the University of Magical Arts you must train an apprentice, and there is no better classroom of magical lore than the ancient tombs and ruined temples of your frequent delves. These NPCs are all examples of ward characters – inexperienced young men and women placed in your care, that, while not yet full-fledged adventurers, still have something to offer.

Ward characters are similar to companion characters, but lack the full suite of attacks and hit points of the latter. They follow you on your adventures for a time, but don’t demand a salary like a hireling or take a share of the XP like a henchman.

Gaining a Ward

Ward characters cannot be bought like a piece of equipment or acquired through training like a feat. A ward is added to the party either as a result of your character’s actions in an adventure, or as a story reward. Once gained, a ward stays with the party as long as it makes sense: until your nephew is safe from the hobgoblin war, the Baron’s daughter grows tired of the hardships of adventuring, or your apprentice has learned your tuition.

Running a Ward

The DM introduces the ward into the game and controls their actions outside of combat according to their individual personality. Generally, a ward has the same level as the party. The ward forms a special bond with a single character in the party who controls their actions during combat. The ward acts during your initiative in a manner similar to a wizard’s familiar, through the sacrifice of your actions. Optionally, depending on the motives of the ward character, after each short rest the ward may form a bond with a different ally (for example, your nephew probably won’t follow anyone but you, but the Baron’s daughter might). A ward can only be bonded to one character at a time.

Ward Characters in Play

A ward has two modes in combat that you can switch between by expending a minor action (by calling for help or giving an order): active and passive.

Passive: a passive ward is not participating in the combat. Perhaps they are hiding in a nearby cupboard, have fled to a safe distance, or are taking refuge in your bag of holding. In this mode the ward does not take up any space on the battlefield.

No Targeting: A passive ward cannot be targeted by any effect.

No Damage: A passive ward cannot be damaged by any effect.

No Benefit: A passive ward’s traits have no effect on any creature.

Active: an active ward appears on the battlefield within 5 squares of you. An active ward listens to your advice and moves around, although they are too inexperienced to make attacks. Unless their description states otherwise, the ward cannot flank an enemy.

Movement: By using a move action, you can move your ward her speed.

Range Limit: Unless otherwise noted, a ward isn’t confident enough to move more than 20 squares away from you. If at the end of your turn the ward is more than 20 squares away, she immediately enters passive mode.

Actions: A ward can take actions (other than attacking) as normal, or use a skill from its skill list, but you must use the relevant action for her to do so.

Ward Character Statistics

All ward characters share the following statistics:

Additionally each ward also gains a special benefit. When the ward is introduced, choose an appropriate role and add the traits to the statistics block:

Notes:

Since I wanted ward characters to be more than just a liability, I looked to existing D&D rules for ‘helpers’ as inspiration. I liked 4e’s approach to familiars (giving up actions for them to do things and their death wasn’t as much of a burden as it was in other editions) and the modular nature of hirelings, so I basically hacked the two systems together. This method might be a bit too gamist for some (the active and passive modes might annoy those who like less abstract NPC mechanics), but I think if it’s run right (the ward whimpering and running off to hide when reduced to 0 hit points for example) it can be fun and won’t break immersion.

It Came from Toronto After Dark: Deadheads

December 2, 2011These It Came from the DVR articles are going to be a little bit different. As an early Christmas present to myself, I picked up a festival pass to the Toronto After Dark film festival. So the first difference is that these are new movies, on the big screen, instead of old ones and niche programming on the small screen. The second difference is that these are going to be short. I’ve got eighteen films to see in seven days (as well as dressing up for the annual zombie walk), so I’m not going to have a whole lot of time to write, and I want post these while the blood is still fresh.

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration, but most of the films it showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

Deadheads

Deadheads mashes together the unlikely genres of zombie, comedy, and road-trip movies to tell the story of Mike and Brent, two strangers that awake one day to find that they have become sentient zombies in the middle of a mindless zombie outbreak.

The two team up and set out on a cross country trek to find Mike’s girlfriend and carry out the marriage proposal he was planning before he died. Along the way the duo tries to cope with undead life and is pursued relentlessly by the shadowy organization that created them.

The Zom-Com With Heart

Toronto After Dark kicked off ‘zombie appreciation night’ (discounted tickets were available for those in costume – a great bit of cross promotion with the Toronto Zombie Walk) with Deadheads. The preview I had seen was pretty funny, but I was wary, as comedy is one of those things that can easily land way off the mark. Co-writer and director Brett Pierce was in attendance and introduced the film as a ‘zombie movie with a lot of heart’, and after seeing it, I have to agree.

There’s so much to like about Deadheads that it makes me want to overlook the film’s rougher patches, which, if you ask me, is the hallmark of something special. The low budget meant that some of the effects weren’t that great (I’m thinking of the digital fire in particular), but the zombie make-up was excellent (a sign that the Pierce brothers knew what was important to spend their limited budget on). Similarly, there were a few slow moments in the middle of the film, but there are enough laughs in the intro and finale to make up for it.

The immediate comparison will be with Shaun of the Dead, which is appropriate since Deadheads works for many of the same reasons its predecessor does (it even uses a similar font for its movie poster). Both films make excellent use of their romantic comedy trappings, poke fun at sometimes ridiculous horror conventions, and feature a hero who must find direction and evolve beyond a life as a directionless loser in the catalyst of an apocalyptic crisis (that last one carries a lot of traction with guys like me).

But what sets Deadheads apart is what it does differently. With the protagonists being zombies instead of fighting them, it’s sort of an inverse version of Shaun of the Dead (and if Romero-esque zombies are code for our consumerist society, finding a way to exist as a conscious zombie might ultimately be a more hopeful message). Also, while Shaun slips its romantic comedy into a survival horror plot, Deadheads uses the road trip movie as its primary plot device… which got me thinking about another Simon Pegg film, Paul.

Now Paul isn’t very good, but its shortcomings highlight what made me like Deadheads so much, and nothing demonstrates the difference between these movies more than a comparison of their respective sidekicks. While the self-titled alien of Paul is hard to look at, irritating and lacks any emotional depth (I’m being a little strong here, but I’m, trying to make a point), Cheese in Deadheads (a regular zombie Mike and Brent bring along in an attempt to train him to stop eating people) instantly connects with the audience with nothing more than a few grunts and facial expressions and has you rooting for the monster from the moment he appears on the screen. Seriously, if a film is able to make me care about the well-being of a mindless flesh eating zombie it’s doing something right.

Deadheads is recommended, and is a must-see for fans of Shaun of the Dead. It isn’t highbrow stuff, but it isn’t supposed to be, and it accomplishes what a good romantic comedy should – it gives the audience what they want and leaves them feeling uplifted.

RPG Goodness

The inversion between protagonist and monster that Deadheads plays with is not new territory for role-players. From early in D&D’s history, players have wanted to use nonstandard races and monsters as PCs (a style of play fully embraced by D&D 3.5’s Monster Manual). It could be that rpgs in general attract people that are a little on the margins themselves, who identify more with the monsters of film and literature than with the heroes. Or it could be that monster PCs just look cool and get a bunch of neat powers to play with. I don’t exclude myself from these observations, as my long running Minotaur gladiator (from 2e D&D) and piano playing vampire (from Rifts) can attest to.

Deadheads is a great example for role-players of the friction between living as a monster and dealing with everyday problems. Deadheads plays this for laughs, and truth be told that’s how these difficulties will probably manifest on most tabletops with monstrous PCs – that is when the party isn’t running from a disgruntled militia or a bunch of angry peasants with torches and pitchforks.

In spite of the popularity of monstrous PCs, the transformation into an NPC monster via infection (through lycanthropy or level drain for example) is still something every player avoids like the plague (zombie plague anyone?). I think the real in-game horror of such transformations has nothing to do with who is a monster and who isn’t, and everything to do with loss of control and agency in the game world. In that spirit I present disease rules modified from 4e for the Gamma World game and the Zed virus (also compatible for D&D games). For the carrier of this plague, the Romero zombie, see my review of Exit Humanity.

The Zed Virus

Disease in Gamma Terra

The laboratories of the ancients are a breeding ground for a cornucopia of genetically engineered super viruses, every bit as dangerous as the radiation and mutant horrors of the wastes.

When a creature is exposed to a disease – whether through a spray bottle of weaponized anthrax or the bite of an infected zombie – they risk contracting the disease. The transmission and effects of a disease follow three steps: exposure, infection and progression.

Exposure

A creature that is exposed to a disease risks contracting it. A creature is typically exposed to a disease through a monster attack (such as the bite of a Romero zombie), or environmental exposure (such as an ancient CDC lab). Unless the disease inducing attack or environmental description states otherwise, an exposed creature makes a saving throw at the end of the encounter to determine if exposure leads to infection. If the saving throw fails, the creature is infected.

If a creature is exposed to the same disease multiple times in the same encounter, it makes a single saving throw at the end of the encounter to determine if the exposure leads to infection.

Infection

Each disease has stages of increasing severity along a track. The effect that exposes a creature to a disease specifies the stage of the disease that applies when a creature is infected (if no stage is specified start with the initial stage). As soon as a creature contracts the disease, the creature is subjected to that stage’s effects.

Unless the disease is removed from the creature (through an origin power or Omega Tech), the disease might progress at the end of the creature’s next extended rest.

Progression

Until the disease ends, unless the description states otherwise, the creature must make a Fortitude check at the end of each extended rest to determine if the disease’s stage changes or stays the same. To make a Fortitude check, roll 1d20 and add your Fortitude score minus 10. A disease typically specifies two DCs. A check result that equals or exceeds the higher DC means the disease is getting better (and moves 1 stage left on the track). If the check result equals the lower DC, or is between the two numbers, the disease remains at its current stage. A lower check result means the disease is getting worse (and moves 1 stage right on the track).

An ally can attempt to care for a diseased patient (using ancient pharmaceuticals, alien nano-tech and whatever else they can scrounge together), substituting their own Science check in place of the patient’s Fortitude check.

When a creature reaches a new stage of the disease, it is subject to the effects of that stage right away. Unless the description states otherwise, the effects of the new stage replace the effects of the old one.

When a creature reaches the final stage of the disease, it stops making checks against the disease. The effects of the final stage are permanent, although a cure might be found in an ancient computer databank, a crashed alien mothership, or growing in one of the seedpods of the sentient mega plant Columbia.

Notes

First I have to give props to Erik Fry, whose blog Dear God What Have We Wrought?! got me thinking about the mechanics of a zombie plague in Gamma World. I went in quite a different direction than he did, but it’s worth checking out if you want a ‘second opinion’ (does this thing look infected?).

While combing through the Gamma World books for mention of disease, I noticed that a few of the character origins (Plaguebearer and Reanimated) have immunity to disease as a character trait. Either designers Richard Baker and Bruce Cordell assumed Gamma World referees would hack the 4e disease rules, or the expansions Famine in Fargo and Legion of Gold were originally intended to have rules for disease. Either way, it makes it a lot easier to introduce disease into the game since the designers already paved the way by giving it consideration.

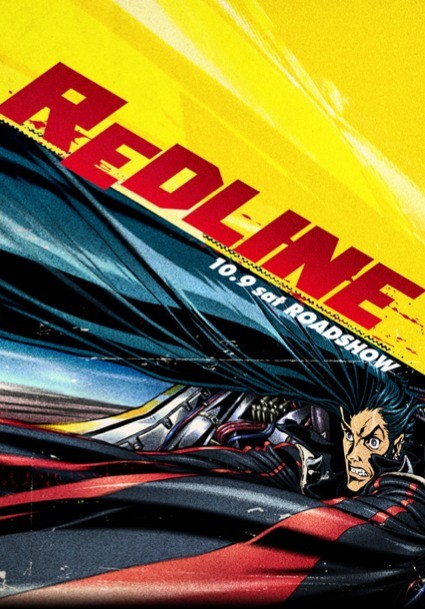

It Came from Toronto After Dark: Redline

November 12, 2011These It Came from the DVR articles are going to be a little bit different. As an early Christmas present to myself, I picked up a festival pass to the Toronto After Dark film festival. So the first difference is that these are new movies, on the big screen, instead of old ones and niche programming on the small screen. The second difference is that these are going to be short. I’ve got eighteen films to see in seven days (as well as dressing up for the annual zombie walk), so I’m not going to have a whole lot of time to write, and I want post these while the blood is still fresh.

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration, but most of the films it showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

Redline

Redline is the animated magnum opus of writer and character designer Katsuhito Ishii, better known in the west as the man responsible for the animated sequences of Kill Bill Vol. 1.

Set in the far flung future, the film follows racecar driver ‘sweet’ JP as he works to qualify for the titular race and move past his days of throwing competitions for the mob. The redline grand prix is deadly, there are no rules and contestants vehicles frequently sport missiles and other weaponry. Because of the collateral damage it causes, redline is held on a different planet each race, the location kept secret until days before the meet.

This Is Your Brain. This Is Your Brain on Redline.

Wow. I wasn’t sure if I was going to make this screening, as it happened smack in the middle of the zombie walk, but I cheated a little (transforming into a fast zombie for a few blocks), and I’m really glad I made it.

I used to be a huge fan of anime, but over the years I’ve sort of drifted away, and haven’t been as zealous keeping up with the latest series and movies. Redline re-ignited my interest and reminded me of the best of what the genre has to offer.

First of all, it’s absolutely beautiful to look at. The highly detailed, hyper-stylized world is full of lurid colors that match perfectly with the high adrenaline story being told (‘high adrenaline’ isn’t quite a strong enough descriptor – more like ‘crank fuelled heart attack’). If you can, see it on the big screen (or at least a big TV) and turn up the volume (the soundtrack was appropriately ‘high energy’). We’ve all heard about seizure inducing anime before, but Redline was the first time I actually thought it could happen.

One more note about the animation. It’s all hand drawn. That means no computer generated vehicles. Honestly, the movie is worth seeing just for that alone (seeing CGI and classical animation jammed together is one of my pet peeves – like a grain of sand in your eye).

Because they share a similar subject matter and medium, the obvious comparison for this film is the classic Speed Racer series, but I think a much better analog is the original Roger Corman classic, Death Race 2000. Both films feature a dystopian future where the race is seen as a way to transcend an oppressive regime, both are light on plot but heavy on the interplay between larger than life racers with tricked out gimmicky cars, and (most importantly) both films share the same sense of fun. The main difference being that Redline pulls off stuff Corman wouldn’t have thought of in his wildest dreams.

Yes, Redline is ridiculous, but the movie keeps on pushing until it becomes sublimely ridiculous. I counted at least four moments during the screening when the whole crowd burst out into spontaneous applause, and I can’t remember the last time I ever saw that during an animated feature.

There isn’t a boring racer in the pack (which is an achievement for any racing movie): bosozoku inspired JP, a cyborg that’s a part of the car, a pair of magical (yes, magical) pop stars that ride in their anthropomorphic vehicle’s boobs, a pair of bounty hunters (one of whom looks exactly like Zoltar from Battle of the Planets) – the most vanilla of all the drivers is love interest Sonoshee and her nickname is ‘cherry-boy hunter’!

Redline is highly recommended, not just for anime fans, but really anyone who wants to see how you can do gonzo right.

RPG Goodness

There is a lot of inspiration crammed into Redline’s 102 minutes. Character concepts, crazy names (my favorite: a Godzilla sized bio-weapon codenamed ‘Funky Boy’), and interesting weapons (the Zoltar-esque bounty hunter has a siege sized grappling gun that tethers his vehicle to faster ones with a chain). All are prime fodder for the rpg table, but the core of Redline is the race, an element that isn’t featured in too many tabletop rpg adventures, despite it being a staple of the action/adventure genre.

Adding a race into D&D is a perfect opportunity to make a skill challenge. I know there are mixed feelings about skill challenges for 4e, but it’s a subsystem that I think is robust enough to both represent a wide variety of activities and also survive judicious tweaking (making it a kind of ‘mini-game’, at the risk of using a dreaded video game term and giving the 4e haters some ammunition).

I should note this skill challenge is a bit different than most, in that it includes a random table and isn’t resolved by the traditional successes vs. failures format (by its nature a race is a competition between individuals). I thought adding some random mayhem into the challenge would be fun and would reflect the craziness of the film.

The Great Race

“It only happens once a decade – a race so dangerous that simply surviving to reach the finish line is a goal worthy of glory. There are no overseers. There are no rules. There is only speed and the blood of the fallen on the dusty road.”

Setup: First, determine the enemy racers. These should equal the number and level of the PCs participating in the race (higher level monsters can be used for a harder challenge, and the number of enemy racers can be decreased if an elite or solo monster is used, or increased if minions are included).

Second, determine the length of the race. Short races are 5 rounds, long races are 10 rounds, and grueling endurance matches are 15 rounds (expect most racers not to finish).

Level: Award XP equal to the value of the monsters used as enemy racers. In long races add additional XP equal to a single monster of the party’s level. In endurance matches add additional XP equal to a pair of monsters of the party’s level.

Running the Challenge: During the first round of the race, roll initiative as normal. In subsequent rounds initiative order is determined by track position, with pole position (1st place) acting first. Using miniatures to determine track position is helpful, but remember, the position on the track is an abstract way of determining where the racers are, not an accurate measure of distance in squares.

Each round, roll on the random event table to set the tone for that leg of the race. Effects from the random event table are applied to racers at the start of their turn.

During their turn, a racer can either advance, block, attack, or recover.

To advance, a racer attempts a moderate skill check. Success indicates the racer has moved up 1 position. Racers who fail this check do not move. If the racer is attempting to move into a position with an enemy blocking creature, the skill check is instead hard. Appropriate skills to advance include (but are not limited to): Acrobatics, Athletics, and Nature (In Gamma World use Str/Con, Dex/Int, and Mechanics checks instead).

Racers can use their turn to block. This makes it more difficult for other racers to enter their position, but also makes it difficult to avoid enemy attacks. Any creature actively blocking grants combat advantage.

A racer can try and attack his opponents to eliminate the competition or settle a personal grudge. A creature can make a melee attack against a racer in the same position, a close attack against a racer in the same or an adjacent position, or a ranged/area attack against a racer one position distant or an adjacent position.

Finally, a racer can take their turn to recover. This allows a racer to take a second wind (allowing the racer to spend a healing surge and granting a +2 bonus to defenses for the round). Unlike the previous actions, a racer can only recover once a race.

At the end of the final round of the race, the racer in the pole position wins. In the event of a tie, all racers in the pole position make a final skill check to advance, and the racer with the highest score wins.

Since the PCs will likely be working together, don’t have the monster racers attack one another (it would become too easy), but don’t have them cooperate in coordinated group attacks either (unless you divide the monster racers into ‘teams’, in which case each team will work together as much as possible).

Optional: If you want the race to be more involved, include the mounts and vehicles for each racer (especially if one or more of the PCs has the mounted combat feat). In this case, close and area attacks affect both racer and mount, while melee and ranged attacks affect either the racer or the mount.

If a racer uses an action point they are able to take two different actions during their turn (but not two of the same action).

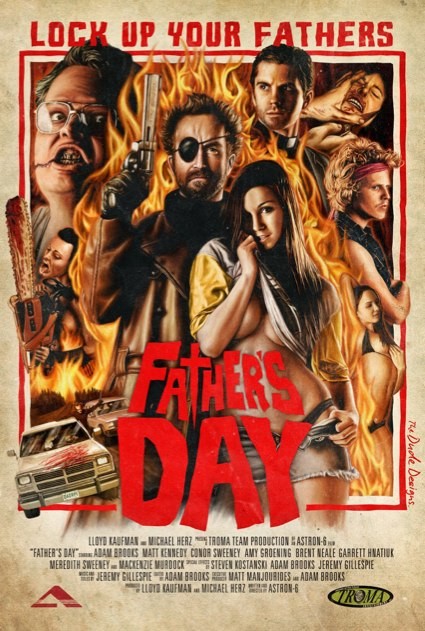

It Came from Toronto After Dark: Father’s Day

October 27, 2011These It Came from the DVR articles are going to be a little bit different. As an early Christmas present to myself, I picked up a festival pass to the Toronto After Dark film festival. So the first difference is that these are new movies, on the big screen, instead of old ones and niche programming on the small screen. The second difference is that these are going to be short. I’ve got eighteen films to see in seven days (as well as dressing up for the annual zombie walk), so I’m not going to have a whole lot of time to write, and I want post these while the blood is still fresh.

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration, but most of the films it showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

Father’s Day

A co-production between Canada’s up and coming, indie film collective Astron-6 and the infamous Troma studios, Father’s Day is the story of vengeance obsessed, one-eyed Ahab and his search for his father’s rapist and murderer, serial killer Chris Fuchman. Fathers are the exclusive target of Fuchman’s depravity – hence the title of the movie. Ahab is joined on his quest by his estranged sister Chelsea (now a stripper), male prostitute Twink (his own father a recent victim), and neophyte priest Father John Sullivan. Gore, nudity and mayhem ensue.

Over the top, retro exploitation

I will admit up front that this movie was not my cup of tea, but I don’t want anyone who reads this to give the film short shrift, because I know there are people who are absolutely going to love Father’s Day. What the movie does, it does brilliantly; I just happen to not really be a fan of the exploitation sub-genre, so most of the work was lost on me.

The Astron-6 guys did an amazing job of capturing the feel of late seventies/early eighties grindhouse pictures, from the look of the film stock (even though it was shot digitally) and minimalist electronic score to the gory special effects (even the movie poster looks like it came from that period). While much of the humour in those older films was unintentional, the laughs in Father’s Day are no mistake.

Since I wasn’t that into other aspects of the film (the torture for instance), I appreciated the comedic bits, which had me laughing out loud. The jokes in the film are a strange (and contradictory) mixture of witty and stupid, often poking fun at many of the horror genre’s unquestioned staples (there are a couple in there I absolutely loved: a kiss for the dying, hallucinogenic berries, the aftermath of the dam fight and the movie’s ending stand out).

Special mention should be made of the gore, which was appropriately over the top. In the Q&A after the screening, the filmmakers described the process they used to prepare the guts of eight pig carcasses for the effects – which had to be done in their own bathtub (a horror show itself). Gore hounds can be rest assured that Father’s Day delivers (including some pretty gruesome genital mutilation).

There was also some funky stop-motion animation thrown in there, which was nice to see, and a hilarious commercial for a Star Wars rip-off halfway through (the film is set up as though it were playing on late-night television).

What I think makes Father’s Day stand out from other recent efforts at retro exploitation is its willingness to subvert the genre (while still clearly enamoured of it). I’ve already mentioned the humour, which works well to this end, but I think the most subversive element of the movie was Astron-6’s choice to make the serial killer rape and murder men (graphically). In horror films (and especially exploitation films) there is a tendency to present women as fetishized objects of sadomasochistic fantasy. I think that modern horror filmmakers too easily swallow this ‘tradition’ without question (no disrespect intended, but I was thinking about Rob Zombie when I wrote that), and perpetuate it. As hard as these scenes are to watch in Father’s Day, I appreciate the point that Astron-6 was making by inverting the convention.

I can honestly say that this was the best Troma movie I have ever seen (which isn’t exactly glowing praise I guess). Father’s Day is recommended for fans of grindhouse exploitation. If you liked I Spit on Your Grave, or Hobo With a Shotgun then this movie is for you. If these kinds of movies aren’t your thing, then Father’s Day isn’t going to change your mind, but at least you’ll get a few good laughs.

RPG Goodness

I like to think that I can draw inspiration from any source, but the subject matter of this movie makes it difficult, to say the least. I would be completely creeped out if my DM ran an adventure based on Father’s Day or statted up the Fuchmanicus for my character to fight, so I won’t be doing either. There was, however, a plot point in the movie that I’ve often thought about incorporating into a campaign…

SPOILER ALERT (seriously, it’s a big one)

In the film, the heroes, in their quest to destroy a demon, must journey to hell to confront it (which immediately reminded me of the 1e D&D convention regarding demon lords and arch devils being destroyed on their home plane). Unfortunately, the only way the heroes can think of to get to the underworld is by committing suicide. In the movie this is played for laughs, but it got me thinking about character death in rpgs.

What if character death were a part of the plot of the adventure, rather than something to be avoided and bypassed (through raise dead)? Now I’m not talking about self-sacrifice (jumping on a grenade to save the party, or hurling yourself into Mount Doom with the One Ring), which I think is common enough in tabletop games. I’m talking about death being the way to overcome an in-game obstacle, like travelling to the lower planes (or the Shadowfell in 4e).

I can think of two D&D products that used character death in this way. The Ghostwalk campaign setting for 3e had dead PCs return as ghosts. Since living characters and ghost characters each had their own strengths and weaknesses, it was advantageous for a party to include both (and not inconceivable to design encounters and obstacles that could only be bypassed by one or the other). The cult classic videogame Planescape: Torment also included a plot point where you could kill yourself to access sealed off areas of the Dustmen’s mausoleum.

Both examples have one key element that I think is important – character death is not final or immutable (because you wouldn’t really be overcoming an obstacle if you were permanently dead would you?). So in our hypothetical campaign where the PCs have to travel to the Shadowfell to combat the forces of Orcus, perhaps at the end of the adventure, as a reward, the Raven Queen can return them to the world of the living.

Alternatively, I think it would be interesting to have death be a side-trek adventure all itself. If a PC dies he or she must complete a small quest in the underworld to return to life (similar to the cliché of challenging Death to a game of chess), assisted by shadow versions of the rest of the party, conjured from the hero’s subconscious. Prophecy is often associated with near death experiences, so instead of treasure and experience points, this kind of adventure can reward the PCs with clues and information about the current campaign. This prize might even be enough to tempt desperate PCs…

Of course this only works if death is relatively rare in the game you are running. Having to run a side trek every other session will quickly become distracting and annoying (not to mention a lot of extra work).

It Came From the DVR: Vampires vs. Zombies

October 9, 2011When I was younger, I used to love nothing more than staying up all night in the cathode ray glow of the television with a bottle of caffeinated beverage by my side, watching such late night fare as Incredible Hulk reruns, badly dubbed kung fu flicks, and rubber suited monster movies. They were hardly Shakespeare, but I’ve found inspiration for writing and gaming in even the darkest dregs of cable television (not everything is redeemable – Charles in Charge comes to mind).

Now that I’m older and (slightly) more responsible, my DVR stays up all night for me, recording a smorgasbord of visual junk food. In this series, I boil that junk down and extract the interesting bits – campaign ideas, adventure locales, encounter set pieces, and of course, monsters.

Spoiler Alert! Yes, spoilers are going to abound. When dissecting a movie or television show to find the hidden awesomeness, you’re bound to reveal things about the plot.

Deadliest Warrior

I am a big fan of Deadliest Warrior. Each episode they use a computer simulation to pit two of history’s greatest warriors against one another, collecting data about weapons, armour and fighting techniques along the way. Yes it’s cheesy, it’s arbitrary and the Americans always win (which is even easier to ensure this season, with the addition of highly subjective ‘x-factors’ to the criteria), but I am a sucker for any show with gratuitous slow motion shots of pig carcasses and ballistics gel torsos being hacked to pieces (I also love Mythbusters). Plus, the trash talk between experts is hilarious.

From a gamer’s perspective, it’s a little like watching Gygax’s fetish for arms and armour come to life, albeit with a few less pole arms. After spending years with some of these weapons on paper, it’s nice to see them in action. Of course, if you’re reading this blog, the odds are you’ve already seen the show. There’s a lot of overlap in the Venn diagram describing people who are gamers and people who wonder if a ninja would win in a fight with a pirate. And if you haven’t seen the show yet, it’s definitely worth checking out for that alone – but I want to talk about the finale.

Vampires vs. Zombies

Now, normally the show deals with real historical figures and martial traditions, but for the season three finale the producers decided to take a sidestep into folklore and pit two iconic undead monsters against one another (depicted here in a mash-up of Clyde Caldwell’s cover of Ravenloft and Jeff Easley’s cover for The Magister). To give their professional opinion and help with the testing, Steve Niles (author of 30 Days of Night, representing the vampires), and Max Brooks (author of World War Z, representing the zombies) were brought in as experts. As would be expected, both by the type of tests they run on the show, and by the version of the undead presented in both Niles and Brooks’ work, the show assumed biological versions of vampires and zombies instead of supernatural ones (so no flying or transmutation for the vamps, and no magically animated body parts attacking on their own for the zombies).

The episode was a lot of fun, and even more gruesome than usual. I heartily approve of using dog and crocodile bites as analogs for the impact of zombie and vampire bites. Once the data was collected, Deadliest Warrior moved on to the real highlight – a hydraulically powered biting machine they used to chew apart a couple of ballistics gel torsos made up to look like a vampire and a zombie to measure the damage the monsters could inflict on one another. The vampire stand-in even had a pumping jugular so they could time how long it would take the creature to bleed out if a zombie got a lucky hit (like I said, they went for the more biological version of the vampire – so they needed blood to survive). I also have to congratulate Max Brooks for taking the smack talk to a whole different level. I easily could have watched a half hour of him bad mouthing vampires and it still would have been entertaining (but then I would have missed out on the biting machine, which would have been a crime).

Not surprisingly, even with the advantage of overwhelming numbers on their side, the zombies lost. Which, as big a fan of zombies as I am, is at it should be. Zombies are mindless, and really only have one strategy, while vampires are at least as smart as mortal humans. They also had the vampires fighting with their teeth and claws, when they could have easily used any of the human weapons featured on the show from the past three seasons. Zombie movies are great, and I think they make a better metaphor for our consumer capitalist society than vampires do, but in an actual fight – vampires win. But really, why would vampires and zombies fight at all? Wouldn’t vampires simply avoid an approaching zombie horde since they don’t have anything to gain by destroying them?

My partner and I usually like to bet on Deadliest Warrior, and in our ‘post-game’ debate these questions came up, which got me thinking (yes we will argue with each other about anything, which should be obvious by how seriously I am taking such a ridiculous show). In combat it’s true that vampires would mop the floor with zombies (as the dramatized portion of the show demonstrated), but when two predators compete with one another in an environment, that’s rarely the factor that determines survival. If it were, the world would be swarming with smilodons and megalodons. Predators compete with one another by stealing the other’s food source.

The problem for vampires is this: both vampires and zombies have the potential to infect others and create spawn, but vampire spawn compete for food (living blood) with their creators so it’s not in the vampires’ best interest to create too many, while zombies just keep making more zombies (since they are mindless and exist only to spread their virus anyway). So while vampires may win the proverbial battle, they will most likely lose the war, as the zombie plague spreads like wildfire amongst their food supply and the vampires are left to die of starvation on a dead planet filled with wandering corpses. It would also put vampires in the strange position of having to risk their ‘lives’ to shield humanity … a scenario rife with possibilities for role playing games.

The Planet of the Dead Campaign

This campaign works best with any post-apocalyptic rpg: Rifts, Gamma World (Gamma Rifts even!), D20 Apocalypse, Mutant Future… but it could also easily work with D&D (especially if you wanted to use the world ending arrival of Atropus from Elder Evils), or even a dark take on Mutants and Masterminds (think Marvel Zombies and the Midnight Sons). Hell, you could probably even use something like Palladium’s Invid Invasion for the Robotech rpg (imagine riding a red and black, vampire built cyclone through the wastelands, fighting giant, gestalt mega-undead formed from the lashed together bodies of hundreds of zombies).

Here is a breakdown of the campaign arc such a game might take.

Outbreak

This short adventure makes a great prequel to the campaign and sets up both the relationships of the PCs as well as setting the tone for adventures to come.

Hours before the global outbreak of the ‘zed virus’, the characters are investigating a series of murders on their home turf. The victims have been drained of blood and suffered horrible neck injuries (which should raise a lot of flags amongst the players). As the deceased are all from vulnerable populations (homeless and sex trade workers), the authorities (police, city watch, etc.) have shown little interest in finding the perpetrator, so it falls to the PC’s to get to the bottom of things (perhaps they were even contacted/hired by the family of one of the victims).

The reality is that a powerful clan of vampires, known as ‘the family’ is using their influence to cover for the indiscretions of one of their more reckless members (you can’t do an end of the world game without at least one nod to The Omega Man). The family is important in the campaign, but doesn’t appear again until the late stages of the game.

The PCs can follow the clues left by the careless vampire to an old tenement building it has been using as a lair (its behaviour has estranged it from the rest of its brethren), but the clock is ticking. Outside, the zed virus is spreading faster than in can be contained, and a shambling horde of the undead is headed the PCs’ way. The vampire seems like the least of the party’s worries when the zombies show up.

An interesting climax to the adventure could be an encounter that transforms from and invasion of the vampire’s lair to a defense of it (perhaps making a temporary truce with the vampire, or maybe a gory three way battle).

Survival

Fast forward six months (or a year) and the world has not fared well. Society has crumbled, the government no longer exists, and the organized war against the zombies has been lost. The battle for survival begins.

The PCs can be wandering nomads, foraging for equipment and supplies, or they can be holed up behind makeshift barricades, venturing out on short treks for food and medicine. This kind of format makes this portion of the campaign perfect for short, goal-oriented adventures (find food, rescue loved ones, etc.), that emphasize the demoralizing hellscape of the post zombie apocalypse.

Dangers abound, not just from zombies, but from other more predatory survivors, the environment and starvation. Encounters with zombies should be varied – the Resident Evil series of games did a great job of making a wide range of monsters to fight by having the t-virus constantly mutating and infecting different animals in different ways (and if the game system already has all kinds of strange creatures you can really go to town when introducing the zed virus).

Getting an infectious zombie bite should always be a threat, but in an rpg it can’t be as virulent as it is in the movies (unless you’re running a Call of Cthulhu game I guess). Players generally expect a higher degree of survivability for their characters than you get in the average horror movie. If you need an in-game reason the PCs get a saving throw, or (if you are using a 4e-style disease) can get better from the virus, perhaps they already have some in-built resistance to the plague that the average person doesn’t benefit from (in a fantasy campaign maybe they have been blessed by the gods, or drank water from a magical fountain).

Pepper these short adventures with rumours of a zombie-free colony of survivors that’s been founded some distance from town (however far it needs to be to make the travel dangerous and memorable). The worse things get where the characters are, the more likely they are to take the hook (and if they were already nomads, getting to this sanctuary may have been their goal all along).

Asylum

Hungry and ragged from the journey, the PCs arrive at the colony, a self-contained complex of hi-tech buildings, complete with armoured greenhouses and its own nuclear power plant (or an impenetrable, walled city with its own self-contained vineyards and orchards in a fantasy game). Amazingly, the colony is as zombie free as advertised and welcomes the PCs with open arms. The place is floor to ceiling gleaming white tile and chrome, bright fluorescent lighting, and most importantly, fully equipped with clean, running water (in a fantasy game the colony would be a neo-classical daydream of the Acropolis, filled with white marble and mathematically precise colonnades). In exchange for residency, given the PCs’ skills, all they need to do is volunteer for the colony’s defense force.

At this point in the game an easy, by the numbers adventure will lull the players into accepting the colony at face value (or not, most rpg players are a pretty suspicious lot – but that’s OK too, the game doesn’t hinge on them being trusting). Under orders from the defence force, a daytime raid against a group of uninfected bandits, or a simple seek and destroy mission to clear a group of undead from a nearby roadway would be good fits.

Once they have begun to settle into their new life, throw the occasional clue about the colony’s true purpose the party’s way: in spite of the steady trickle of survivors coming in, the colony never seems to run out of room or resources; the PCs have never met or seen any of the people who defend the colony through the night; the colony’s leaders are constantly shifting people from one living area to another – every week it seems the PCs have new roommates and neighbours; there is no crime in the colony, yet the PCs haven’t seen any internal police. It won’t take much for the PCs to want to investigate further.

The Bloody Truth

Eventually the PCs will use whatever means they have (force, guile or subterfuge), to get to the bottom of who really runs the colony – a group of vampires called the family (possibly including the vampire they fought at the beginning of the campaign, if it escaped), protecting a small pocket of humanity from the zed virus to preserve their food supply.

The PCs might stumble onto direct evidence of the family (using whatever means of vampire detection are suitable to the game and type of vampires it features), or they may break into the core of the family’s secret activities in the colony – a cavernous, refrigerated vault underneath the colony’s reactor that houses a living blood bank. Hundreds of comatose humans, hooked into a web-like network of intravenous tubes, some providing just enough sustenance to keep these poor souls alive, while the blood they produce is slowly leached away by others (a fantastic image courtesy of the film Daybreakers).

As more and more survivors make their way to the colony, the family adds more bodies to the blood bank, always making sure to keep enough free humans to supply a healthy breeding stock. Preference is given to those humans with highly trained skills, powerful defenders (like the PCs), and pregnant women. Criminals, agitators, and dissidents are all prime candidates to be taken to the blood bank.

Endgame

The endgame of the campaign is completely dependent on the actions of the PCs (which goes without saying for any part of the campaign, but here especially so). As distasteful as it is, the party might decide to maintain the status quo. Sacrificing a portion of the population might be deemed a worthwhile price for the vampires’ protection against the zed virus and the continuance of humanity. The challenge for a party that takes this road is in convincing the family that they will keep the vampires’ secret. Doubtless the family will arrange for tests of loyalty which might be as dangerous as fighting the vampires themselves (and since the family’s opinion might not be unanimous, this is a great opportunity for high stakes political intrigue and espionage).

Most rpgs are action oriented, and many of the players I know would want to take the other road, overthrow the family and free the enslaved humans. The challenge here is obvious and could be played out as a climactic Helm’s Deep type battle between the vampires, their minions and whatever freedom fighters the PCs can muster together (you could even throw in an ill-timed zombie attack for good measure), or as a series of guerrilla attacks between the PCs and the vampires (in between which they must once again fare for themselves in the zombie infested wasteland).

There is also the possibility that some PCs will want to side with the family, while others will want to destroy the vampires. You should definitely be prepared for some inter party conflict here. Emotions can run high in these situations and it might be a good idea to call a session before the PCs decide what they are going to do (think about the fate of Rorschach in Watchmen – some players might be cool with that, while it could ruin the campaign for others).

Vampires as PCs

Many of the game systems mentioned feature the option of playing as a vampire. At first glance it might seem a bad idea to include these character options, but they can add an interesting twist to the whole campaign. The vampire PC might already be a member of the family (and should be prepared for some of the previously mentioned conflict at the end of the campaign), or might be a member of a different group of vampires just as ignorant of the colony as the other PCs (and might be equally horrified by the activities there). A vampire PC won’t automatically side with the family any more than other PCs will automatically want to fight them.

The Flesh Mime and Other Belated Updates

September 24, 2011 Ménage à Monster slowly stirs from its torpor, gathering the strength to birth more horrors into the world… But this isn’t a lame filler post (well not entirely) – unlike my last post, I actually have real content to present. It just happens to be on another website.

Ménage à Monster slowly stirs from its torpor, gathering the strength to birth more horrors into the world… But this isn’t a lame filler post (well not entirely) – unlike my last post, I actually have real content to present. It just happens to be on another website.

At the end of August, the good reptilians at Kobold Quarterly posted one of my creations on their website: the flesh mime.