These It Came from the DVR articles are going to be a little bit different. As an early Christmas present to myself, I picked up a festival pass to the Toronto After Dark film festival. So the first difference is that these are new movies, on the big screen, instead of old ones and niche programming on the small screen. The second difference is that these are going to be short. I’ve got eighteen films to see in seven days (as well as dressing up for the annual zombie walk), so I’m not going to have a whole lot of time to write, and I want post these while the blood is still fresh.

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration, but most of the films it showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

Love

Set in the near future, this film focuses on the life of astronaut Lee Miller during a solo mission on board the International Space Station. Shortly after his arrival, something goes terribly wrong on the planet below and all communication stops. Alone, Miller must deal with crushing loneliness and the dangers of the aging space station. Hidden amongst the junk of previous crews, Miller finds an old journal written during the American civil war that hints at a profound secret. As the astronaut begins to lose his mind, fantasy, reality, and the mystery of the journal begin to bleed into one another.

Visually Stunning, Emotionally Charged

Love is not a film people are going to feel ambivalent about. Standing in line for the movie that followed the screening, it was apparent that festival goers who had just seen Love had very strong opinions about it. I enjoyed Love immensely, and I’m not sure if it was the lack of sleep this far into the festival, but the movie had a pretty big emotional impact on me as well.

Before I go into Love’s merits, I think a good litmus test on whether you are going to hate this film depends on what you feel about 2001: A Space Odyssey – If you dug the second half of that movie (when Dave is alone on the ship, up to and including the funky space warp with the monolith), then I think that Love is for you. But 2001 isn’t for everybody, and neither is Love. I should also confess that I like the movie Solaris, so if that throws my judgment into question, I’ll understand.

Before making Love, writer and director William Eubank worked as a cinematographer, and it shows. Love is absolutely beautifully shot. There were moments, especially the civil war battle scenes, that I can honestly say are some of the best looking filmmaking I have ever seen. After the screening Eubank announced that the film is being distributed on iTunes, and I’m glad it will reach a wider audience, but it also pains me to think it won’t get a proper theatrical release because I’m not sure you’ll be able to see the depth of detail on the small screen. One scene in particular stands out in this regard – an amazing slow motion shot of a charging soldier where you can see the individual particles of dust being blown off his uniform by the shockwave of a nearby exploding mortar shell. Amazing stuff.

Contrasted with the wide open, vividly colored civil war and fantasy scenes, Eubank creates a space station whose muted colors and oppressive atmosphere are cranked up to a Das Boot level of claustrophobia. Actor Gunner Wright takes full advantage of this in his role as the astronaut (which is good since he’s on screen for the main chunk of the film). His performance pulled me into Miller’s world, and aside from a few hiccups (he’s been in space how long?), kept me there for the full hour and a half.

The most incredible thing about Love though, and I still find it a little hard to believe given how good it looks (have I gushed enough yet?), is that the entire thing was shot in the back of Eubank’s parents’ ranch, with all the sets built by Eubanks in his spare time. Even if you hate the movie (and I’ll admit there were quite a few haters in the audience), you have to be impressed by what the filmmaker was able to accomplish with the little he had. Did I also mention it was shot with borrowed cameras?

I referenced 2001 earlier, and the DNA of Kubrick’s heritage is strongly manifest in Love. There will always be cries of rip-off when a film wears it inspiration on its sleeve like Love does, but I feel it just manages to steer shy of being derivative and say something new. Love shares many of 2001’s themes (isolation, madness, the meaning of humanity), as well as some superficial elements (most of which are spoilers), but goes about exploring them on a tangential course. Ultimately, Eubanks has very different things to say about people than Kubrick does, and each film elicits a very distinct emotional response.

Love is recommended, especially for fans of 2001 who want to see a different reading of similar themes. Even if you aren’t a fan of that kind of film, I recommend tracking down the civil war scenes and watching them on as large a screen as you possibly can.

RPG Goodness

Unlike most stories, which use clues or revelation to propel the plot, the driving force of Love is the absence of information (communication with earth ceases). It might be counterintuitive, but I think it’s a technique that can be applied to rpgs both to foreshadow future adventures and to inject a little verisimilitude into the game world.

Beginning with the rumor table in the venerable Keep on the Borderlands (Bree-Yark means ‘I surrender’ in goblin language), and evolving into skill checks to gather information (or Streetwise or Conspiracy), D&D adventures have a long history of enticing players to progress to the next stage of the plot with packets of information. I think that the absence of information can be just as motivating to players, driving them to seek out the answers.

As an example, instead of introducing the module Against the Giants with the Grand Duke informing the players that an alliance of giants has overrun the western portion of his dominion, pique their curiosity by telling them the grand duchy hasn’t heard from any of the villages bordering the Crystalmist Mountains in weeks. The PCs, dispatched to find what has happened, can find evidence of giant attacks and as the adventure progresses, will come to realize the attacks are the result of a sinister group of masterminds organizing the disparate races of giantkind. By starting with nothing, and uncovering the facts of the mystery themselves, the PCs ‘own’ the information, and are much more motivated to advance the plot of the adventure than if they felt the mystery was someone else’s (and therefore someone else’s problem – sorry Grand Duke, not interested).

Providing the players with gaps of missing information also works well when introduced into the campaign in the middle of a different adventure. That way the mystery stays at the back of the players’ heads while they deal with more pressing matters, and when the issue comes up again later in the game (or escalates) it seems more organic and less like a video-game series of quests to tick off (thank-you for collecting eighteen squirrel tails, now I need a letter delivered…). The absence of information can sometimes be just as important as a rich background for making the game world come alive.

Love also tackles the theme of isolation, which is difficult to apply to rpgs in an existential sense, but when thought of more practically, is a powerful tool in the DM’s arsenal (so powerful in fact, that it should be used sparingly or it will grow old very fast). The old adage, ‘don’t split the party’ is true for a reason, and nothing panics a group of adventurers like being isolated against their will. Pits (the Dungeon Master’s Guide has the standard example but my favorite is the pivoting floor and wall from Pyramid of Shadows), portcullises (from Dungeon Master’s Guide II) and conjured walls (just add the wizard class template to a monster and choose wall of fire, wall of ice or the forcecage power) are all excellent devices to separate members of the party from one another, especially when combined with a combat encounter. If you are feeling extra devious, use this tactic while toying with the players’ impatience – stagger the combat encounter so the panicking players waste their most powerful abilities and resources on weaker creatures before the ‘big bad’ shows up (to reiterate, use sparingly if you don’t want to be pelted with dice).

The falling cage is a staple of evil throne rooms, does an excellent job of separating the party without separating them from the action, and I have yet to see one in a 4e adventure. For that reason I present my own take on this classic trap.

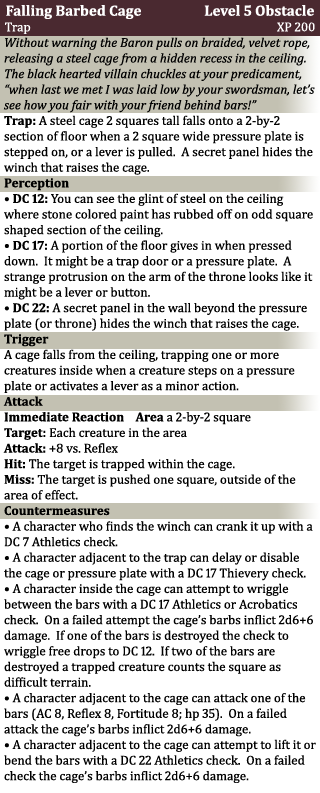

Falling Barbed Cage

This trap works best in a combat encounter where the pressure plate is located between the party and a controller or artillery type monster, optimally along an obvious path of least resistance. Alternatively, you can give control of the trap to one of the monsters, who waits until the characters are in position to activate the trap.

The falling barbed cage doesn’t inflict very much damage on its own, but is excellent at occupying and pinning down strikers and defenders that rush forward to attack soft targets.

Tags: 4e, Blather, D&D, Pop Culture