These It Came from the DVR articles are going to be a little bit different. As an early Christmas present to myself, I picked up a festival pass to the Toronto After Dark film festival. So the first difference is that these are new movies, on the big screen, instead of old ones and niche programming on the small screen. The second difference is that these are going to be short. I’ve got eighteen films to see in seven days (as well as dressing up for the annual zombie walk), so I’m not going to have a whole lot of time to write, and I want post these while the blood is still fresh.

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration, but most of the films it showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

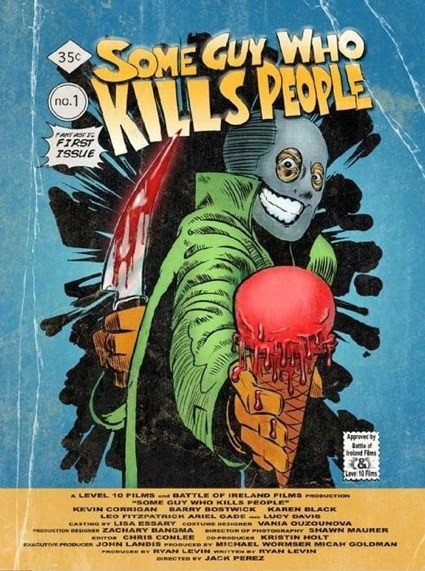

Some Guy Who Kills People

In this dark comedy, all of Ken Boyd’s problems can be traced back to the traumatic bullying he endured during high school. It drove him to attempt suicide, which led to a stint in a mental hospital and now the only work he can get is a humiliating job at an ice cream parlour. Living with his bitter and sarcastic mother, Ken trudges along the rut of his life… but everything changes when his estranged teenage daughter comes to stay with him and Ken’s tormenters start dropping like flies.

Dark, Sweet, and Funny

I expected Some Guy Who Kills People to be dark (it pretty much spells things out in the title), and funny (the trailer was hilarious) – and the film delivers. What I didn’t expect was how sweet Some Guy Who Kills People is. It’s rare to find a black comedy without a cynical bone in its body, but this film makes it work. Maybe the murder and revenge keep the movie from descending into corniness and the sweetness keeps it from sliding into ironic despair. I’m not sure, but it’s a nice balance. You could call it ‘dark chocolate for the funny bone’ (eat your heart out Chicken Soup for the Soul!).

That balance that I mentioned takes great acting to pull off, and Some Guy could have been a disaster without it. Kevin Corrigan is wonderful as the painfully awkward Ken, but isn’t so unreachable that you don’t feel sympathy for the guy when he has to cater the birthday party of one of the bullies dressed as a giant foam rubber ice-cream cone (and if it wasn’t painful it wouldn’t be nearly as funny). Karen Black also does a good job as Ken’s harpy mother with a heart of gold (if you watch Burn Notice imagine Michael Weston’s mom, but instead of growing up to be a super-spy he had a dead-end job and still lived at home). Barry Bostwick is hilarious as the bumbling local Sherriff (although bumbling isn’t really the right word – more like ridiculous) – anchoring much of the movie’s humour with straight-faced certainty and absolute deadpan delivery. Holding her own amongst these veteran actors (shining even) is Ariel Gade as Ken’s young daughter. I think I might even go so far as to say that her sincere performance, filled with spunky optimism, is the heart and soul of this film. I see from her IMDB page that she’s been in a few movies I’ve watched (Dark Water, and Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem), but I have no memory of her (sorry). If Some Guy gets wide release, her relative anonymity will change, because it will catapult Ariel Gade’s career like Little Miss Sunshine did for Abigail Breslin.

I’ve focused on the lighter elements (because they really stand out in a festival like Toronto After Dark) but it isn’t all gumdrops and lollipops, there’s also murder and death. The kills are creative and funny, though I would have liked them to be a little bloodier (not Saw level violence mind you, but a little absurd, over the top arterial spray would have added something).

Some Guy Who Kills People is recommended. It’s a nerd fairy tale; watch it when life’s got you down and you want a revenge fantasy with your happily ever after.

SPOILER ALERT

I really only have one criticism of the film, but it’s wrapped up in a spoiler so I wanted to put it down here. I won’t give too much away, but towards the end of the movie is a big plot twist (which is a spoiler if you’re looking for it the whole time). At the end of the day it felt sort of awkward, as the mystery is one of those reveals, which is full of information that isn’t given to the audience prior to the twist. I also felt it undermined what the filmmakers were doing with one of the main characters, since you cheer for him in spite (maybe because) of the murders. It doesn’t ruin the movie; it just felt like they pulled their punch a little at the end.

RPG Goodness

Although the murders in Some Guy Who Kills People are funny (and the victims are unrepentant douchebags), they are also unequivocally ‘bad’ (as in ‘not something a good person would do’). Watching the film with rpgs on the brain, I couldn’t help but think that the actions of the serial killer in Some Guy would not be out of place on the tabletop, and might not even be considered all that bad depending on the context they were committed within. If the bullies happened to be a cabal of evil wizards in a dark tower, the PCs wouldn’t think twice about breaking into their home and slaughtering them in cold blood. If though, like in the film, the bullies were just a bunch of 0-level commoners from town, things should be different.

The context of the PCs actions in both scenarios is informed not only by the morality of their alignment, but also by what I like to call the ‘frontier mentality’ (since it plays out very much like a western). Things are dangerous in the wastelands and dungeons outside of civilization and the stakes are life and death. Though mercy is expected of the noble, hostility is most often met with brutal violence. On the other hand, once back behind the walls of society (‘in town’), adventurers need to heed the law and start acting civilized again. The frontier mentality is something I like to play with in my games, by placing NPCs in town that I know will get the goat of the players, just to see if they can keep their swords in their sheaths (hey, DMs are allowed to have fun too). I think using the scenario of the film (the PCs running into childhood bullies in town) would make for an exciting and tense encounter, especially if the bullies pose no physical threat (can the PCs resist the temptation?).

The arrival of Ken’s teen daughter in the film got me thinking – what would the PCs do if they had to bring a young dependant along with them on their adventures? Instead of being a hassle, what if it was actually a reward? The appearance of a young companion or sidekick that the hero is responsible for is a staple not just of comedies but also of action/adventure movies and comic books. In spite of this, the only similar situation I can recall in my own games was when we made use of a table in 2e’s Complete Book of Bards– if a bard’s fame score was high enough a number of special events could occur, one of them being an obsessive 0-level fan that followed the character into dangerous situations. While the crazed fan proved to be a lot of fun, he was hardly a benefit to the party. I think that sidekicks can be both a boon and a liability (as they are in comics and films), so here I present guidelines for ward characters in D&D.

Ward Characters in D&D

After the hobgoblins of the red hand destroy your village, you must escort your feisty nephew to safety, out of the reach of the war. Your renown has brought you to the attention of the indulgent Baron of the Nentir Vale, who volunteers you to take his headstrong daughter with you on your next adventure. In order to fulfill your obligations to the University of Magical Arts you must train an apprentice, and there is no better classroom of magical lore than the ancient tombs and ruined temples of your frequent delves. These NPCs are all examples of ward characters – inexperienced young men and women placed in your care, that, while not yet full-fledged adventurers, still have something to offer.

Ward characters are similar to companion characters, but lack the full suite of attacks and hit points of the latter. They follow you on your adventures for a time, but don’t demand a salary like a hireling or take a share of the XP like a henchman.

Gaining a Ward

Ward characters cannot be bought like a piece of equipment or acquired through training like a feat. A ward is added to the party either as a result of your character’s actions in an adventure, or as a story reward. Once gained, a ward stays with the party as long as it makes sense: until your nephew is safe from the hobgoblin war, the Baron’s daughter grows tired of the hardships of adventuring, or your apprentice has learned your tuition.

Running a Ward

The DM introduces the ward into the game and controls their actions outside of combat according to their individual personality. Generally, a ward has the same level as the party. The ward forms a special bond with a single character in the party who controls their actions during combat. The ward acts during your initiative in a manner similar to a wizard’s familiar, through the sacrifice of your actions. Optionally, depending on the motives of the ward character, after each short rest the ward may form a bond with a different ally (for example, your nephew probably won’t follow anyone but you, but the Baron’s daughter might). A ward can only be bonded to one character at a time.

Ward Characters in Play

A ward has two modes in combat that you can switch between by expending a minor action (by calling for help or giving an order): active and passive.

Passive: a passive ward is not participating in the combat. Perhaps they are hiding in a nearby cupboard, have fled to a safe distance, or are taking refuge in your bag of holding. In this mode the ward does not take up any space on the battlefield.

No Targeting: A passive ward cannot be targeted by any effect.

No Damage: A passive ward cannot be damaged by any effect.

No Benefit: A passive ward’s traits have no effect on any creature.

Active: an active ward appears on the battlefield within 5 squares of you. An active ward listens to your advice and moves around, although they are too inexperienced to make attacks. Unless their description states otherwise, the ward cannot flank an enemy.

Movement: By using a move action, you can move your ward her speed.

Range Limit: Unless otherwise noted, a ward isn’t confident enough to move more than 20 squares away from you. If at the end of your turn the ward is more than 20 squares away, she immediately enters passive mode.

Actions: A ward can take actions (other than attacking) as normal, or use a skill from its skill list, but you must use the relevant action for her to do so.

Ward Character Statistics

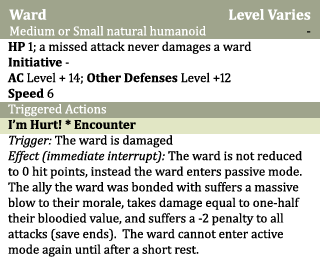

All ward characters share the following statistics:

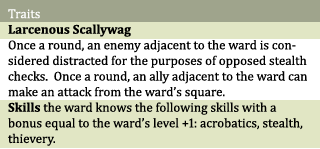

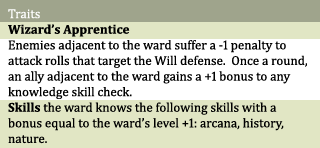

Additionally each ward also gains a special benefit. When the ward is introduced, choose an appropriate role and add the traits to the statistics block:

Notes:

Since I wanted ward characters to be more than just a liability, I looked to existing D&D rules for ‘helpers’ as inspiration. I liked 4e’s approach to familiars (giving up actions for them to do things and their death wasn’t as much of a burden as it was in other editions) and the modular nature of hirelings, so I basically hacked the two systems together. This method might be a bit too gamist for some (the active and passive modes might annoy those who like less abstract NPC mechanics), but I think if it’s run right (the ward whimpering and running off to hide when reduced to 0 hit points for example) it can be fun and won’t break immersion.

Tags: 4e, Blather, D&D, Pop Culture