Posts Tagged ‘3e’

Random Encounters: The Shackled City for Pathfinder (Chapter Three Flood Season)

October 5, 2012Currently I am running a Pathfinder campaign for my gaming group, and since I never got the chance to use my copy of The Shackled City hardcover while we were playing 3.5 I figured it wouldn’t be too much work to convert to ‘3.75’. In spite of Paizo’s claims of backwards compatibility, you can’t really use 3.5 D&D adventures off the shelf for Pathfinder. Most of it works, but the monsters and NPCs in particular are too weak to be a real challenge to a party of Pathfinder characters. Converting the stat blocks isn’t impossible, but it does take time, and since I’m doing the work anyway (I’m a bit of a stat block perfectionist) I thought I would share (click on the pictures at the end of the article to download PDFs of the updated stat blocks for all the monsters and NPCs as well as some additional handouts I created for the third chapter). You can find a conversion of the first chapter of the adventure path, Life’s Bazaar, as well as Pathfinder-style versions of the Greyhawk gods here, and the second chapter, Drakthar’s Way, here.

SPOILER ALERT

Obviously there are a ton of spoilers here, both for the campaign and the adventure. So if you plan on playing in The Shackled City, peeking ahead is going to ruin a lot of the fun. If you are one of my players, it goes without saying that you shouldn’t read any further. You’ve been warned.

Flood Season

The following changes should be made to the adventure for it to play smoothly using the Pathfinder edition of D&D. Click on the pictures at the end of the article to download a PDF of Pathfinder stat blocks for every NPC and monster in the adventure (when I DM I like to have the monster stat blocks in front of me, instead of having to flip to the back of the book or shuffle through Bestiaries), as well as a few additional handouts useful to the adventure (some handbills advertising Flood Festival events, double-sided invitations to the Demonskar Ball, maps that the PCs can buy to aid them at the Lucky Monkey, the symbol of the Ebon Triad, and an excerpt from Skaven’s scroll detailing the kopru civilization).

Event 6: Meet the Competition

I added a class level to each of the Stormblades to maintain their original CR. Since there isn’t a Swashbuckler base class in Pathfinder I made Cora Lathenmire a Fighter – with her choice of feats and skills she will still be able to take levels in the Duelist prestige class later in the campaign.

Inside the Lucky Monkey

M1. Common Room

I added a level to both the alleybashers and the hillfolk to maintain their CR in Pathfinder. I also slightly altered the hillfolk to give them more of an Olman flavor (the jungle barbarians that live in this area of the World of Greyhawk). I traded out their masterwork longswords for obsidian war clubs (with the stats of a masterwork warhammer), but kept their armor (assuming they had acquired chainmail through raiding or as payment from Triel). If you want the Hillfolk to be more of a traditional European barbarian, just give them longswords.

M21. Courtyard

The hill baboon was never updated in any of the Pathfinder books, so I replaced them with advanced chimpanzees, but kept the description and flavor.

M27. Kitchen

Tongueater was a mess. As originally presented, Tongueater was an infected lycanthrope, which adds a needless amount of rolling for the DM and doesn’t really add anything to either the story or the game – so I changed him into a natural lycanthrope. The second problem was that Tongueater was given levels of Barbarian, a class restricted to non-lawful alignments (and Tongueater is LE), so I switched these out with levels of Ranger (and took the two-handed weapon combat style from the Advanced Player’s Guide to keep him as a falchion wielder). Finally, the way CR works with lycanthropy and class levels is slightly different in Pathfinder, so he wound up with 5 class levels instead of 3. Even after all these changes I still think that my version of Tongueater maintains his core identity – a ferocious melee combatant able to tear through PCs quickly.

For DMs interested in a little more flavor than ‘120 pounds of loot worth 4,500 gp’ I broke it down as follows:

- A large painting of the setting sun on a far horizon with a darkwood frame (taken from area M15); 300 gp; 5 pounds.

- A case of 12 bottles of fine wine from the Holds of the Sea Princes; 10 gp each; 18 pounds total.

- 4 bottles of Keoish brandy; 20 gp each; 8 pounds total.

- Assorted silverware; 100 gp; 10 pounds total.

- A pair of gold candleholders, elegant in their simplicity; 100 gp each; 2 pounds total.

- Silver dinner service, embossed with native Amedio fruits and animals; 500 gp; 7 pounds total.

- 4 golden monkey statuettes with chipped emeralds for eyes; 500 gp each; 15 pounds total.

- A sea chart of the trade winds of Jeklea Bay and the Northern Azure Sea; 200 gp.

- A letter of bond for Maavu’s Imports; 500 gp (a great set-up for the next chapter).

- A lapis ornamental comb; 75 gp.

- A silver mirror with folding cosmetics plate; 50 gp.

- A small bottle of spicy smelling perfume oil; 25 gp.

- 7 moonstones; 50 gp each.

M39. Battlefield

Switch out Sarcem’s 3.5 style periapt of Wisdom +2 with a Pathfinder headband of inspired Wisdom +2 (since the item is a headband, you might consider keeping it with Sarcem’s head in area M27.).

M43. Well Room

I added an additional class level to Shensen in order to maintain her CR, following the guidelines for her advancement in the appendix of the hardcover.

Event 10: Information for Sale

I added an additional class level to Artus in order to maintain his CR. I interpreted his high ranks in Use Magic Device as an interest in magic so I gave him the Rogue talents of minor magic and major magic.

The Kopru Ruins

K7. Nightmare Beach

The skulvyn has never been updated to the Pathfinder game so I replaced it with a fiendish bunyip. It’s not a perfect fit, but it’s fairly close (and I get the impression the skulvyn was chosen only to showcase the then-released Monster Manual II).

K8. Kopru Lair

The kopru has never been updated for the Pathfinder game, but rather than substitute another monster I decided to rebuild it using the monster guidelines in the Bestiary (as the race plays such a central role in the adventure). Since it’s essentially a new monster for the game, I included the extended stat block in the PDF (and now that the work is already done, the kopru makes a perfect candidate for the next installment of Classic Monsters).

K13. The Gauntlet

The Reflex save DC for the pit trap here should be DC 20, as that is now the standard for all pit traps regardless of CR.

K16. Workroom

The mud slaad has never been updated to the Pathfinder game (and won’t be by Paizo as slaad are considered WOTC intellectual property) so I replaced it with a cerberi. This is a case where I think the replacement works better than the original. Thematically, the cerberi is a better fit for the role of leftover mystic guardian.

K24. Skaven’s Parlor

With arcane lock, the Disable Device check to pick the lock is DC 40 and the door’s break DC is 38.

I added a class level to Skaven to maintain his CR. In 3.5 diviner Wizards only had a single opposition school, in converting Skaven to Pathfinder I added the opposition school of conjuration as that didn’t have any effect on the spells he had memorized.

In addition to the scroll on the kopru (included in the PDF of handouts) Skaven’s collection of esoteric books contains the following:

- The Last Will and Testament of Lawethika of Ket

- Ruminations of Charnel Fulminations

- The Hours of Tintinnabulatory Twilight

- Fragments from the Digested Notebooks of Tenrast Inktongue, a Blackmailer

K25: Skaven’s Bedchamber

With arcane lock, the Disable Device check to pick the lock is DC 40 and the door’s break DC is 38.

K27. Spider Nest

Spiders are one of the monsters that went through a lot of changes between 3.5 and Pathfinder, messing up the sizes and CRs of the spiders presented in this adventure. In order to maintain CR replace the small spiders in this room with 2 spider swarms.

K30. Webbed Cavern

In order to maintain the CR of this encounter, replace the medium and large monstrous spiders with 4 giant spiders and 1 giant black widow.

K31. Ettercap Lair

This room should have 3 ettercaps for the given CR.

K32. Harpoon Spider Lair

The harpoon spider has never been updated for the Pathfinder game (and I suspect it was included in the adventure for the same reason as the skulvyn), so I replaced it with another intelligent arachnid foe, the phase spider (which could just as easily be worshipped as a god by ettercaps). I made two slight modifications to the phase spider’s stat block to better reflect the adventure. I changed its alignment to NE to reflect Skaven’s corrupting influence on the creature and I gave it Common instead of Aklo, since there is no Greyhawk equivalent of that language.

K33. Trapped Chamber

The poison on the spikes should read as follows:

Medium Spider Poison—injury; save Fort DC 14; frequency 1/round for 4 rounds; effect 1d2 Strength damage; cure 1 save.

K36. Triel’s Chamber

I added a class level to Triel to maintain her CR.

K41. Bloodbath

The bloodbloater ooze has never been updated for the Pathfinder game so I replaced it with an amoeba swarm. While technically the amoeba swarm could crawl out of the pit in search of food, I assumed their preference for an aquatic environment and regular feedings would keep them in the pit.

K50. Undead Ogres

The pair of ogre zombies are slightly below the target CR, but the skeletal tyrannosaurus in area K48. is so brutal it more than makes up for it.

K52. Cult Treasury

The spawn of Kyuss have never been updated for the Pathfinder game so I replaced them with a pair of giant crawling hands. I’ll admit it’s not a perfect fit, but the giant crawling hands are the right CR, and their pus burst has a similar gross-out factor as the spawn of Kyuss’ worms.

The poison on the chest should read as follows:

Nitharit poison—contact; save Fort DC 13; onset 1 min.; frequency 1/min. for 6 min.; effect 1d3 Constitution damage; cure 1 save.

K55. Undead Minions

There should only be 6 zombies in this encounter for the target CR. Just so these monsters wouldn’t seem exactly the same as the zombie ogres in K50., I used the plague variant included in the Bestiary (plus, I hoped they would make up for the missing spawn of Kyuss in K52.).

K56. Tarkilar’s Cavern

Huecuva work very differently in Pathfinder then they did in 3.5 so it was next to impossible to do a straight conversion of Tarkilar. Instead, I rebuilt him from the ground up. Starting with a standard huecuva, I added class levels of Cleric until I hit the target CR (adding class levels also gave the huecuva a bonuses to its stats, which I used to replicate Tarkilar’s original stats as closely as possible). I also fiddled a little with the standard racial skills and feats of the huecuva in order to better emulate the original Tarkilar. Finally, I allowed the huecuva’s disease to be spread through the creature’s weapon attacks (it is wired directly into his flesh, so the spiked chain is probably filled with all sorts of disgusting bits of rotting gnoll flesh).

It Came From Toronto After Dark: V/H/S

July 17, 2012As I mentioned in an earlier post, I’ve been lurking at the Toronto After Dark film festival’s summer screenings (if you’re in the GTA don’t miss the main event, October 18-26). Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration. Most of the films the festival showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

Roleplaying games helped foster an unhealthy love of monsters, which hooked me at an early age to genre films, which in turn help to inform my tabletop games (in a weird kind of feedback loop). This ongoing series of articles takes these influences and mashes them together to create a strange hybrid I call It Came from the DVR (although I seem to be in the theatre more often than in front of the television, but I’m not complaining – they have better snacks).

V/H/S

V/H/S

A group of maladjusted vandals and budding snuff filmmakers are hired to break into a lonely old house and steal a unique VHS tape. A simple enough job, complicated by a creepy room filled with random tapes, a wall of televisions, and something even more disturbing. As the vandals watch the tapes, looking for their prize, they are given a window into a frightening world that threatens to drag them in.

Anthology and Found Footage Combine for a Deliciously Scary Peanut Butter Cup of Film

V/H/S was conceived as a creative challenge to a group of independent filmmakers to revitalize the saturated sub-genre of found footage horror. Like any anthology, there are hits and misses, but overall the film succeeds at what it set out to accomplish – providing some truly frightening moments that had me gripping the armrest in the theatre.

First, if you haven’t seen the film yet I strongly urge you to avoid the trailer if at all possible since it spoils some of V/H/S’s best parts. It won’t ruin the experience, but I found myself waiting for scenes from the trailer to pop up during the screening, which sort of killed the surprises a few of the segments had to offer.

I’ve mentioned before that I’m a fan of horror anthologies, and I really enjoy a good found footage film (The Blair Witch Project, Paranormal Activity and Cloverfield come to mind) so I had fairly high expectations going in to V/H/S. I wouldn’t say the filmmaking of the individual segments exceeded those expectations (and in some cases didn’t meet them), but what made V/H/S really stand out was how well it utilized both formats and how well those formats complemented one another. In fact, I would go so far to say that V/H/S has spoiled me, and I’m not sure I’ll be able to see another found footage film without thinking that it probably would have been better cut down to fifteen minutes and included as part of a larger anthology. The general problem with found footage films is that they tend to be slow, with the worst having huge chunks of filler, and that slowness gives the audience plenty of time to question the verisimilitude of people continuing to film themselves during horrible events (the main conceit of the sub-genre). V/H/S avoids that pitfall by nature of the format leaving little room for filler. Each segment cuts to the chase fairly quickly and, in addition to some pretty good justifications for the protagonists filming themselves, the audience really doesn’t have a lot of time to question the suspension of disbelief.

I really dig the concept behind the wraparound tale by Adam Wingard. It provides an excellent framework for the film, which is actually pretty rare in an anthology, and moves the viewer from one segment to the next efficiently and smoothly (overall I have to commend the filmmakers for using visual styles, that while different, didn’t clash with one another). There are some odd pacing choices that I wasn’t expecting and, given how despicable Wingard makes his characters, I was a little disappointed he made their comeuppance so unspectacular (off screen for the most part).

The first segment by David Bruckner, about a trio of frat boy types with a set of spy-cam glasses is predictable but has a good payoff (and monster), some excellent practical effects work and a nice punchline worthy of Creepshow 2.

After the lacklustre The Innkeepers, I’m starting to think that Ti West and I just don’t see eye to eye. His segment here, which documents a young couple’s cross country road trip, takes one of the most unsettling hooks I’ve seen in a long time and throws it away with an ending that isn’t just lame, but also cheats the whole found footage format. It’s really too bad, because if it had been executed better, West’s story could have had real staying power, clinging to the audience’s subconscious long after leaving the theatre.

Joe Swanberg’s segment, a series of haunted Skype conversations between long distance partners, also stumbled during its finale, but was so original and had some of the best scares in the entire film that it’s easy to overlook its shortcomings. There’s a really killer reveal at the end but it’s just a bit too long and shows just a bit too much. This segment freaked me out while I was watching and a more subtle ending would have amplified that fear, rather than helped to dissipate it. I’ve also got to call out Swanberg for the gratuitous boob shot in what is essentially the segment’s epilogue. I get that found footage taps into the whole amateur porno aesthetic (there is an 1980’s era slasher flick level of breasts in this film), but it just felt tacked on and a little silly in what was otherwise a super creepy end note (a nit-pick of mine I’m sure many others don’t care about).

Glenn McQuaid’s segment presents a unique take on the ‘college kids camping in the woods’ story that both tweaks film convention and has an unexpected justification for the protagonists filming it. The best part is how McQuaid explores the medium of found footage and its place in the horror continuum while still delivering the entertainment goods. Plus it introduces a super cool monster with a concept I don’t think I have seen before.

The final tape in the anthology is also my favorite. The Radio Silence collective show how to do a haunted house story right with their segment about a group of friends on Halloween looking for a party. The pacing here is perfect, starting with some nice subtle creeps and building to a great climax. When things start to get crazy, we are treated to a smorgasbord of supernatural sights and sounds that I won’t be surprised to see imitated by other horror filmmakers very soon.

V/H/S is recommended and is a must see for fans of The Blair Witch Project and the Paranormal Activity series. I’m not sure it will change the minds of die-hard haters of found footage, but it stands amongst the better entries of the sub-genre and is a good reminder of why those films are an important addition to the horror lexicon.

RPG Goodness

One of the reasons found footage works so well in a short format is that it has a very noticeable point of view, which gives the audience a lot of information quickly about the character filming it just by how it is shot without the need for exposition. It’s a technique DMs can utilize themselves by incorporating ‘found documents’ (standing in for found footage) into their campaign.

I’m a bit of a handout junkie in my games, so I don’t really need an excuse but, in my experience, found documents require only a little effort on the DMs part to create and add a tremendous amount of atmosphere to the game. There is a long history of using found documents as adventure hooks in D&D (the Return to the Tomb of Horrors mega adventure has some of the best), and running across a scroll or stack of papers that documented any of the tales in V/H/S would make a very memorable adventure (Joe Swanberg’s segment would be hard to reproduce but could be created as a series of correspondence). My preferred method of including found documents in a game though is as an item of treasure.

Most adventures involve thwarting a villain’s evil scheme or stopping a (sometimes complex) plot or conspiracy from coming about. The only problem is that most of the time the players only learn the broad strokes of what they are dealing with, and then move on to the next adventure. The finer details and the villain’s motivations are often left to be enjoyed only by the DM (unless you’re running a supers game and do the whole ‘now that you’re captured, let me tell you about my plan’ thing). By introducing found documents into the monster’s lair you can share this information with the players and give them a glimpse into the mind of the foe they have just fought.

The form such a document takes is important to keep in mind as it will help get across as much information about the one who created it as the point of view the camera tells the viewer in a found footage film. Organized, methodical minds (i.e. Lawful) might make a journal or a detailed ledger of accounts while unorganized or insane minds (i.e. Chaotic) might make rambling manifestoes or smear poetry on the walls in an unwholesome substance. Just remember you don’t need to recreate a whole document in order for it to get the point across to the players. V/H/S shows just how much story you can tell with a short excerpt (although in found journals I do like to include one or two short entries with no solid information but that helps to paint a portrait of the author’s personality).

The other thing DMs can take away from viewing V/H/S is inspiration for new monsters – scads of them (over email Toronto After Dark festival director Adam Lopez joked that you could create a whole game out of the monster material in V/H/S, and he’s not far from the truth). My favorite was the creature from Glenn McQuaid’s entry, presented for the Pathfinder game below. It’s a tiny bit spoiler-y, so if you haven’t seen the film yet, check it out before using the new monster in your game.

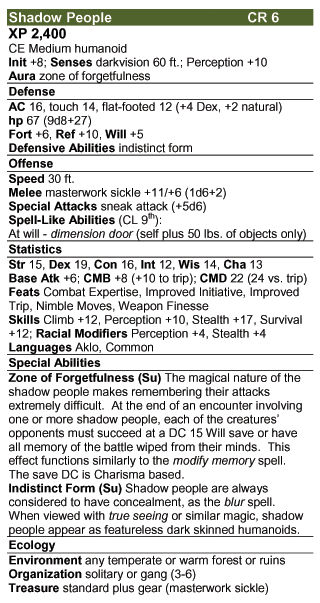

Shadow People

Shadow People

Your eyes can’t seem to focus on your pursuer, though glimpses out of the corner of your eye of its bloody attack on your camp give you the impression of a dark, humanoid shape… indistinct images that even now begin to slip unnaturally from the grasp of your memory.

The shadow people are enigmatic and malicious magical creatures that dwell in lonely wilderness locations and abandoned ruins. They are extremely territorial, viciously attacking and tormenting any intelligent creature that passes too near their homes. Any fortunate enough to survive an attack by the shadow people and resist their magical aura can be guaranteed a lifelong enemy, for the creatures’ greatest fear is that outsiders will spread word of their existence to the outside world.

Consequently, there is very little information regarding the nature or origin of the shadow people beyond general warnings that a particular patch of woods is haunted. Brave adventurers moving through shadow people territory though might find faded pictograms, or ancient runes carved into crumbling pillars that tell the story of a group of assassins, cursed by the gods for slaying a beloved priestess to be forever erased not just from history, but from memory itself.

It Came From Toronto After Dark: The Pact

July 6, 2012As I mentioned in an earlier post, I’ve been lurking at the Toronto After Dark film festival’s summer screenings (if you’re in the GTA there’s still a chance to catch the second night of screenings on July 11 – Detention and V/H/S). Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration. Most of the films the festival showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

Roleplaying games helped foster an unhealthy love of monsters, which hooked me at an early age to genre films, which in turn help to inform my tabletop games (in a weird kind of feedback loop). This ongoing series of articles takes these influences and mashes them together to create a strange hybrid I call It Came from the DVR (although I seem to be in the theatre more often than in front of the television, but I’m not complaining – they have better snacks).

The Pact

The Pact

After their estranged mother’s death, Annie’s sister convinces her to return to the family home and help put the estate in order. A reluctant Annie arrives only to find her sister missing and a growing, frightening supernatural presence. Emotionally raw, with plenty of reminders of her painful childhood, Annie attempts to uncover the mystery of her sister’s disappearance.

Solidly Delivers on the Creeps

The Pact isn’t going to blow anyone’s mind with originality (and the most clever parts of the script are the things I thought were the weakest – more on that below) but it does what it does extremely well and that’s deliver an extraordinarily creepy atmosphere. It’s got all the trappings audiences have come to expect from supernatural suspense films: eerie figures moving off screen from the corner of the frame, apparitions suddenly appearing behind the protagonist, a medium who goes into paroxysms of terror when she enters the house, spirit photography and, of course, a Ouija board that moves on its own. Nothing ground-breaking. Then again, those tropes are repeated so often in the genre because they work, and writer/director Nicholas McCarthy knows how to use them effectively. For example, McCarthy does an excellent job letting the audience know that a certain door in the house is very bad, just through the use of composition, music and the reaction of Annie. It’s a great technique that is hard to pull off well (the 1963 version of The Haunting is another great example), but one that is excellent at ramping up the tension. That build-up is essential in supernatural suspense because the actual jump-out-at-you scares are sparse; you’re kept glued to the screen by the threat that something bad could happen at any minute – and McCarthy uses this to make a dated suburban bungalow seem as creepy as on old gothic manor.

McCarthy’s best ally is actress Caity Lotz in the role of Annie. Lotz’s ability to project the character’s emotional scars, without tons of script exposition, gives Annie an unexpected depth that I found engaging and sympathetic. She was also fantastic at supercharging her character with the kind of expressive fear that really sucks the audience in – you can get away with just standing there and hysterically screaming in a slasher (they’re supposed to be a bit cartoony) but suspense thrives on authentic emotion. Lotz’s reactions felt real, and I almost cheered when during her first encounter with the supernatural, she reacts by blindly lashing out at her attacker and getting the hell out of the house as fast as she possibly can. I really hope she continues to work in the horror genre.

While I was hooked into the creep fest that was the first three-quarters of this film, I felt that the last act of The Pact fell short. Much of the creepiness of the movie flows from not knowing, but the inevitable reveal of the film`s mystery robs The Pact of its scariest elements (which is the inherent trap of any mystery – not revealing anything would have been even worse). During the film’s climax when I should have been biting my nails, I almost felt kind of safe, since the sense of dread McCarthy had built up so well was completely dissipated (see more under the spoiler tag). The Pact is not alone in making this kind of mistake; I felt that to a lesser extent even Insidious suffered from this, so McCarthy’s work is at least in good company.

Despite of my complaints, The Pact has enough going for it that I recommend it to those that like the suspense horror genre and don’t need a big scary ending to enjoy a film. If you’re spending the evening in on a dark and stormy night, I think it would make a great double bill with Stir of Echoes.

SPOLER ALERT

As I mentioned previously, the big revelation in The Pact is the film’s most original moment, and is cleverly executed, but is also its weakest point. Once you realize that the supernatural force is merely trying to warn Annie, and that the real threat to those in the house is decidedly human, the film got a lot less scary. I might be in the minority, but a mundane flesh and blood killer is much less frightening to me than a haunted house with freaky ghostly manifestations where anyone who spends the night disappears without a trace.

I do have to give kudos to McCarthy for not cheating the plot though; everything about the revelation made sense without invalidating the first three quarters of the film (even the sounds made sense, an excellent little detail I really appreciated). When I see so much lazy writing on film and TV, especially where any kind of mystery is involved, it’s very refreshing to see something thought through from the beginning. I just wish it hadn’t sucked all the scariness out of the film for me.

RPG Goodness

The Pact is a great resource for DMs who want to inject some supernatural suspense into their games since it’s a veritable dictionary of the tropes of the genre – and more importantly – shows how to execute them effectively. As I mentioned in my review (with the example of the sinister door), one of the ways that McCarthy creates suspense is through the use of indirect information. Incorporating this trick into the DMs toolbox is a little counterintuitive in a game with a long history of ‘read aloud’ boxed text, but is one that can help to create a really creepy atmosphere for the right kind of adventure. Continuing with the example of the door, a similar situation at the game table might traditionally go something like this:

“The door at the end of the hall radiates palpable waves of fear and dread. As you move closer the feeling intensifies and you have to clutch your weapons tightly to keep from trembling. You press on even as every instinct screams that there is something very wrong here…”

There is nothing wrong with running an encounter this way (and it’s a pretty good in-game cue that there’s some kind of fear effect in play without being too gamey), especially if it isn’t pivotal to the adventure. However, if the door is central to solving a mystery, and if the party are going to pass by the location several times, it helps to build suspense by slowly layering indirect information to the players instead of coming right out and telling them the door is bad. Here are some examples of indirect information using the aforementioned sinister door:

- If the characters make a point of keeping the door closed, have them find it open and vice versa.

- Familiars and animal companions won’t overtly freak out, but always move in such a way that they avoid the door (a Perception check might reveal this to observant characters), and won’t cross its threshold unless forced.

- Characters walking by the door might get a sudden chill and see their breath in the cold pocket of air.

- A character who makes a moderate Knowledge (engineering) check realizes the door is in an odd location in relation to the rest of the structure and isn’t something most architects would build.

- Characters who put their ear up against the door to listen hear someone on the other side whispering things about them, but the room beyond is empty.

- Instead of their usual effect, divination spells regarding the door result in ominous automatic writing.

- Characters searching the area who succeed at a hard Perception check notice a single torn and bloody fingernail lodged between the stones of the door’s sill.

Inheriting a Haunted House

The Pact (as well as the Poltergeist series), has another great lesson for DMs – the best hauntings are by multiple spirits with distinct personalities and goals (something especially important in D&D given the way that ghosts work mechanically). This keeps the PCs on their toes, sows confusion if they assume they are dealing with a single spirit, and helps to up the creep factor by having an in-built narrative (with more than one ghost wandering around there’s got to be some kind of story there).

The easiest (and most classic) way to introduce this kind of adventure into the game is to have one of the PCs inherit property that turns out to be haunted. Alternatively, the party could be asked by an NPC contact to protect an inherited estate from wandering brigands while they put their affairs in order (and as payment they are welcome to whatever knickknacks and baubles are lying around).

To be a true haunted house, it should be the lair of at least two or more ghosts. Perhaps in life, one was murdered by the other out of jealousy and the murderer, now a ghost herself, prowls her hard won acquisition to keep intruders out and her crime a secret (and won’t rest as long as her reputation is publicly intact). The murder victim tries to warn those who spend any time in the house but as a ghost, his communication is limited to the frightful moan ability (and won’t rest until his body is retrieved from its shallow grave in the cellar). If you’ve seen The Pact, then the last quarter of the movie holds a further complication that can be recreated in a haunted house adventure (one that I think would work a lot better in a D&D adventure than it does in the film).

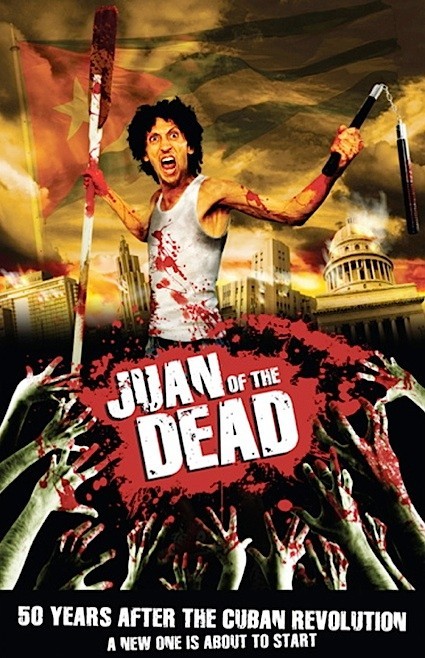

It Came From Toronto After Dark: Juan of the Dead (Juan de los Muertos)

June 29, 2012As I mentioned in an earlier post, I’ve been lurking at the Toronto After Dark film festival’s summer screenings (if you’re in the GTA there’s still a chance to catch the second night of screenings on July 11 – Detention and V/H/S). Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration. Most of the films the festival showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

Roleplaying games helped foster an unhealthy love of monsters, which hooked me at an early age to genre films, which in turn help to inform my tabletop games (in a weird kind of feedback loop). This ongoing series of articles takes these influences and mashes them together to create a strange hybrid I call It Came from the DVR (although I seem to be in the theatre more often than in front of the television, but I’m not complaining – they have better snacks).

Juan of the Dead (Juan de los Muertos)

Juan of the Dead (Juan de los Muertos)

In Havana, ne’er-do-wells Juan and Lazaro find themselves in the middle of a zombie outbreak sweeping across Cuba. Amid the chaos, Juan tries to make amends to his estranged daughter, survive, and if he plays his cards right, maybe even turn a profit while he does it.

Surprisingly Fresh for a Film about Walking Corpses

Juan of the Dead surprises on many levels – and keeps you laughing while it does it. The first thing I noticed was how good it looks. Cuba doesn’t export a lot of movies, so walking into Juan I had every expectation that a zombie flick from Cuba would out of necessity have to be put together with bubble-gum and stock footage. It turns out my assumptions were completely unfounded (or Cuba has some pretty awesome magic bubble-gum). The zombie make-up looks great, there is ample blood (some of it CGI but there’s enough practical gore to satisfy horror lovers), and filmmaker Alejandro Brugues manages to use the visual language of classic zombie films (machetes, baseball bats, and crouching undead feasting on the entrails of the fallen) while expanding the repertoire with some really creative and fun kills (both zombie and human). The film had the support of the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC) so, in addition to the better than expected cinematography Brugues also had access to many of Havana’s most recognized landmarks which provided some beautiful visuals all their own.

The involvement of the Cuban government is surprising not just because Juan is a horror-comedy, but also because a lot of its humor is driven by political satire (in the film, government officials refuse to recognize the zombies as undead, calling them ‘political dissidents’ instead). Perhaps the film’s political grumbling is palatable when mixed with a heavy dose of physical comedy, genre commentary (after they realize what they’re up against, the main characters have a great conversation about the nature of the undead), and general zom-com fun and silliness. I find the context in which the film was made fascinating. It adds a tension to the whole thing that works very well with the suspense and dread inherent in any apocalyptic tale (even a comedy).

The group of misfits at the film’s core are funny and instantly likeable, in spite of their sometimes despicable actions and questionable personalities. In another context they might easily be villains, but the script’s humor and the actors’ charisma are enough to charm the viewer into almost liking the characters because of their failings (something viewers of Shameless will be familiar with).

After great movies like Shaun of the Dead, Zombieland and Deadheads, I was worried the sub-genre would run out of juice, but Juan of the Dead’s final surprise is that zombie comedies still have fresh things to say and new ways to entertain. Sure there’s some overlap (and I caught a great shout out to Peter Jackson’s Dead Alive), but no more than between any given group of romantic comedies. Juan of the Dead is more than just the Cuban take on the zom-com (although it is also very much that), it’s also a film about fatherhood. Through Juan’s relationship with his daughter, Brugues explores the competing interests of being your own man, doing what you need to do to survive and transforming into the kind of role model our children want us to be (all while never taking itself seriously).

Juan of the Dead proves the zom-com is here to stay. I highly recommend this film – there are plenty of brains yet to be eaten and laughs to be had at a crumbling civilization’s expense.

RPG Goodness

Plot twists (and back stories) involving the PCs’ parents are familiar (and fun) territory when it comes to ‘campaign complications’. Juan of the Dead (and my own steadily growing age) got me thinking in a slightly different direction. What if, like the main character of the film, the PCs’ lives are complicated by the appearance of an estranged child?

Of course this campaign complication comes with its own unique obstacle – the small matter of the child’s origin. If the player is willing to have their PC begin the campaign a little older than most starting characters, then it’s easy to introduce the child as an established part of the character’s backstory. If not, it’s easy to imagine the wild adventuring lifestyle producing an unplanned child or two at some point in a PC’s career (what with tempting succubi, charming assassins and amorous demigods running around). When the campaign calls, settling down to be a responsible parent is not in the cards (and is about as fun to role-play as operating a fruit stand), and the friction begins.

The storytelling possibilities for this kind of complication are near limitless, and if the player is willing to go along with it, can provide a lot of drama, comedy, and fun at the table. Here are a few possibilities:

- After hauling chests full of a slain dragon’s hoard back to town, one of the PC’s is tracked down by their bastard daughter, who immediately demands her right to inheritance.

- A larcenous and chaotic PC’s son is a devout worshipper of St. Cuthbert (or other Lawful deity), who checks up on his parent from time to time in order to make sure they remain ‘on the straight and narrow’.

- The PC’s daughter has gotten herself involved in the Cult of Elemental Evil (or some other villainous organization). Is she a lost cause or can the PC repair their relationship and convince her to abandon her wicked way of life?

- One of the PC’s is confronted by their son, who has just married into a wealthy and powerful family. He is embarrassed by his parent’s adventuring life and asks the character to retire or change their name. If they are aren’t willing to do either he uses his newfound coin and influence to ‘convince’ them to do so.

One of the things I really like about complications involving children is that even in an antagonistic situation; combat isn’t always the easy choice. I once pitted my gaming group’s party against a band of wild orphans, led by a sorcerous twelve year old (she attacked with animated toys). It was obvious to the players that although they were suffering damage, the children were merely acting out, their leader in the throes of a fierce tantrum. Since the PCs didn’t want to have the slaughter of children on their heads, subdual, diplomacy and bribery were the strategies of the day.

Variant Zombies for Pathfinder

Juan of the Dead isn’t just about parents and their kids; there are also quite a few zombies – the classic kind of zombie that doesn’t die unless you shoot it in the head. I really like the zombies that are presented in the Bestiary for Pathfinder. I think the fast zombie and plague zombie variants that are included go a long way to bringing the D&D zombie more in line with the tropes of horror cinema. At the risk of setting off an edition war (not here please, I like both editions plenty) though, I think that the 4e Monster Manual may have done it better. In this edition of the game, zombies are especially vulnerable to critical hits, which just screams ‘shoot it in the head’ to me. Fortunately, it isn’t hard to bring that mechanic into Pathfinder via a variant zombie simple template. I even think it’s possible to improve on the 4e design by emphasizing how hard the walking dead are to kill unless you destroy their brain.

Unrelenting Zombie

“Just shoot them in the head! They seem to go down permanently when you shoot them in the head.”

Some zombies are possessed with a particularly relentless and evil will. These creatures shrug off most wounds, and only complete bodily destruction or the obliteration of their putrid brain can stop them from their pursuit of the flesh of the living.

Defensive Abilities: An unrelenting zombie gains DR 10/-. This ability replaces DR 5/slashing.

Weaknesses: An unrelenting zombie gains the following weakness.

Critical Vulnerability (Ex): A confirmed critical hit roll against an unrelenting zombie destroys the monster’s brain, reducing it immediately to 0 hit points. Additionally, any attack against the unrelenting zombie with extra sneak attack damage applied, bypasses the zombie’s damage reduction.

Notes:

When combined with the plague zombie simple template (minus the change to DR), I think you’ve got the perfect Romero (or Juan) style zombie for Pathfinder. With both templates applied, add +1 to the creature’s CR.

Random Encounters: The Shackled City for Pathfinder (Chapter Two Drakthar’s Way)

June 27, 2012Currently I am running a Pathfinder campaign for my gaming group, and since I never got the chance to use my copy of The Shackled City hardcover while we were playing 3.5 I figured it wouldn’t be too much work to convert to ‘3.75’. In spite of Paizo’s claims of backwards compatibility, you can’t really use 3.5 D&D adventures off the shelf for Pathfinder. Most of it works, but the monsters and NPCs in particular are too weak to be a real challenge to a party of Pathfinder characters. Converting the stat blocks isn’t impossible, but it does take time, and since I’m doing the work anyway (I’m a bit of a stat block perfectionist) I thought I would share (click on the pictures at the end of the article to download PDFs of the updated stat blocks for all the monsters and NPCs as well as some additional handouts I created for the second chapter). You can find a conversion of the first chapter of the adventure path, Life’s Bazaar, as well as Pathfinder-style versions of the Greyhawk gods here.

SPOILER ALERT

Obviously there are a ton of spoilers here, both for the campaign and the adventure. So if you plan on playing in The Shackled City, peeking ahead is going to ruin a lot of the fun. If you are one of my players, it goes without saying that you shouldn’t read any further. You’ve been warned.

Drakthar’s Way

The following changes should be made to the adventure for it to play smoothly using the Pathfinder edition of D&D. Click on the pictures at the end of the article to download a PDF of Pathfinder stat blocks for every NPC and monster in the adventure (when I DM I like to have the monster stat blocks in front of me, instead of having to flip to the back of the book or shuffle through Bestiaries), as well as a few additional handouts useful to the adventure (a remade copy of Terseon’s letter using my version of the Cauldron arms as a seal; the symbol of the Cagewrights burnt onto the storage crates; and a few examples of goblin graffiti – I tried to keep them primitive and crude).

Jil’s Tip

Jil’s total bonus to Disguise, including all modifiers and her disguise self spell, is +25. She has a Challenge Rating of 5 instead of 6.

Rats in the Bathhouse

Orak’s challenge rating is reduced from a 4 to a 3. I kept him the same level in spite of this, since even at CR 4, Orak isn’t much of a real threat to a well-equipped party (he hasn’t got any armor or a decent weapon). The wererats, who are the real combatants in this encounter, are the proper challenge rating.

Wandering Monsters

I used Tricky Owlbear Publishing’s version of the ethereal filcher from the PFSRD, which is only a CR 2 instead of the called for CR 3. Rather than beefing the creature up, I kept it as is, since an encounter with this creature is all about preventing it from stealing your magic items – not protracted combat.

6. Storage

The rules for determining CR for creatures with class levels are slightly different in Pathfinder than 3.5e, which means that 1st level goblin rogues only have a CR or ½ instead of 1. To compensate, I gave them another level in rogue. Alternatively you could keep them as level 1 rogues and increase their numbers.

13. Adept’s Lair

Like the goblin sneaks, in order to maintain a CR of 3, I increased the level of the goblin adepts. Since this only results in more spells, not a new spell level, it shouldn’t be problematic.

17. Silent Wolf Goblins

Normally I try and maintain feat choice between the 3.5e and Pathfinder versions of NPCs. In this case I broke that rule and substituted Mounted Combat for Dodge. The adventure states that the silent wolf goblins get off their mounts to fight on the ground in combat, but I ignored this for a few reasons: it seems like a waste letting the goblin’s high ride checks go unused; the cramped layout of the map means that combat space is at a premium; and most importantly, the image of a dual-wielding goblin riding into battle on the back of a worg is just too awesome to pass up. I also added an extra level of rogue to maintain the creature’s original CR.

26. Mercenary Quarters

To maintain Chorlyndyr’s CR of 4 I added another level of Sorcerer (since it doesn’t result in a new level of spells). However, I kept Kallev at 4th level and lowered her CR to 3 – even with the pair bickering, this is a tough encounter and Kallev has a ton of hit points.

31. Drakthar’s Throne Room

Drakthar’s throne, a unique creature, seemed heavily based off of the 3.5e version of the skeleton, so rather than attempting to translate it, I used a Pathfinder version of the skeleton with enough hit dice to reach CR 3, and added a pair of claw attacks (with damage appropriate to the CR) as well as blindsight.

To create Drakthar I added the vampire template to a stock bugbear (even though technically it should only be added to a creature with at least 5 hit dice), substituted putrefy corpse for create spawn and lowering his energy drain to a single level (the standard two levels seems high for a party of 3rd level characters, and his fast healing is challenge enough all by itself).

35. Half-Orc Mercenaries

Like most of the monsters with class levels in this adventure, I added a level of expert to Xoden and a level of fighter to the Half-Orc mercenaries to maintain their CR.

A Note on Magic Items

In my previous post on the Shackled City, I never explained the strange codes in the lists of NPC gear. It isn’t a typo. One of the practices I picked up DMing 3e games that I’ve carried over into Pathfinder is coding all the magic items in the campaign. There are so many magic items (especially one-shot items like potions and scrolls) that it’s easy to forget where they came from in the time between ‘looting the body’ and getting the item identified. To help keep track of everything, I simply give the players the item’s code when they find it, and refer back to a master list when the item is identified. For potions I also add a visual descriptor to help identify the concoction by sight. Each particular type of potion has a standard description, which helps provide some internal consistency to the game world and speeds up the identification process (my players now know that when they find syrupy, red potions they can start using them immediately to heal).

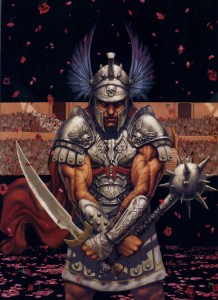

The Best Dungeon Covers: 76-fin

June 8, 2012This is the second (and final) installment of my celebration of Dungeon magazine’s 200th issue (click here for the best cover art of the first 75 issues). The latter half of Dungeon’s print run was an interesting time for the magazine. It saw the rise of 3e and the founding of Paizo. Even more importantly though, it was in the pages of Dungeon that the ‘adventure path’ format was born – a series of adventures linked together by an overarching plot (taking characters from 1st level to 20th) – a campaign in serial form. Dungeon’s adventure paths set a new standard in the industry and the format proved so successful that Paizo was able to base their entire business around publishing them when WOTC cancelled the print versions of Dragon and Dungeon …and spin that achievement into their own version of D&D at least as successful as 4e (I wouldn’t hesitate to say that the Pathfinder rpg owes its existence to the development of the adventure path).

If Dungeon is 200 why stop at issue 150? As I mentioned in my retrospective on Dragon magazine covers, cover art lost its place of cultural primacy when the magazines underwent their digital rebirth (you can see a similar phenomenon with album art in the age of iTunes). Digital covers don’t serve the same function (a combination of product packaging and advertisement), and as a result have little influence on the gaming world – the equivalent of a vestigial organ. That might sound harsh, but it’s not an indictment of WOTC’s digital initiative (I think the accessibility, low cost, and portability of PDFs are great), just a lamentation for a lost art form. Let’s take a look at some of Dungeon’s best examples and remember a time when cover art was king (click on images for full size).

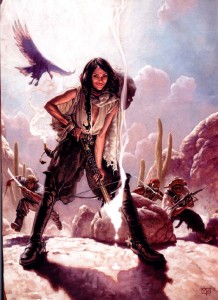

I fell in love with the cover to issue 80, by Mark Zug, the moment I laid eyes on it. The mash-up of D&D and the wild west is fantastic, irreverent and avoids descending into campiness. The two visual themes blend together so well that neither the hats nor the crossbows seem out of place (the magical bolt standing in for a smoking shotgun). But that’s not what draws the viewer’s eye immediately to the center of this piece – it’s the wicked smile of the character in the foreground (Tonja, the leader of a group of desert bandits in the adventure Fortune Favors the Dead). Imbuing a figure with real personality, as Zug has done, is extraordinarily difficult (that’s why portraiture is so demanding). That smile is so compelling I wonder how many people have overlooked that the bandit leader is supposed to be an NPC and used this cover as a character portrait.

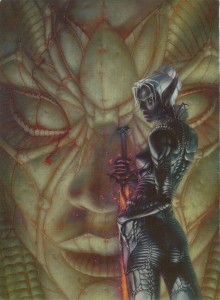

Another femme fatale, Laveth the daughter of Lolth, courtesy of Stephen Daniele for the cover of Dungeon 84. There’s a bit of cheesecake going on in this painting (especially that ‘America’s Next Top Model’ pose) but the artist’s ability to capture the essence of the drow so well elevates it above mere fan-service. Daniele is definitely channeling H.R. Giger’s biomechanical work here (always a good thing in my opinion), and it fits perfectly. Laveth’s armor looks like the chitinous shell of a spider, a great visual cue that not only ties the drow to the goddess of arachnids, but also reminds the viewer that everything about the dark elves is twisted, alien, and dangerous. The pale statue in the background, with clusters of spiders that look like bloody tears, is a nice touch as well.

The cover for Dungeon 90 is, aside from his Dark Sun work, one of Brom’s best paintings (and there are a lot to choose from – Brom’s works have made it onto all but one of my lists of the best Dragon and Dungeon covers). It features a priestess of Loviatar and her undead ally. The devourer, rendered in pale ghostly tones is very much in (what I call) Brom’s ‘gothic mode’. The evil spirit is truly frightening, and the pathetic soul of a vanquished paladin trapped within its ribcage makes this cover a strong argument for why the devourer, added to the game during 3e, is an instant classic. What makes this painting one of my favorites among Brom’s work though, is the figure of the priestess. I love her blood red monochromatic color scheme, and the artist’s choice to give her a more exotic, non-European look is something you don’t see often in the art of D&D and it’s a refreshing departure.

It would have been easy to fill this list with nothing but Wayne Reynolds’ paintings – he created a tremendous number of Dungeon covers during the 3e period most of them were exceptional. While he still dominates this list, I opted instead for his best four (plus a bonus cover at the end). Even if you aren’t a Reynolds fan, you have to be impressed with the sheer volume of the work he put out during these years (and he still produces an impressive output for Paizo).

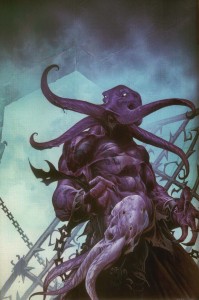

Reynolds’ cover for issue 94 features one of my favorite monsters, the craziest mind flayer villain of all time, Absterthelid, a creature with a taste for the brains of his own kind (a great idea made insane by a stat block that combined mind flayer and monk to take advantage of the mechanics of the extract brain special ability – truly a monster). Reynolds takes the classically cerebral image of the mind flayer and transforms it into a beast of physicality. The cast-off, brainless husk of a traditional mind flayer completes the image, giving the viewer everything they need to know about both Absterthelid and Reynolds’ larger than life approach to illustration.

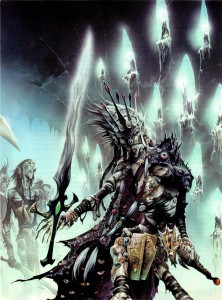

Dungeon celebrated its 100th issue with ‘incursion’, an event spread between Dungeon and Dragon that saw the githyanki invading the prime material plane. It’s a very cool concept (one that I planned to incorporate into a long running Planescape campaign, but never got the chance to), and Wayne Reynolds’ painting of Vlaakith, the lich-queen of the githyanki is even cooler. Though her physical form is withered and mummified, Reynolds leaves no question as to Vlaakith’s arcane might. I especially like Reynolds’ disturbing take on the robe of eyes, a fitting accoutrement for a queen who sustains herself with the life force of her subjects. Reynolds sometimes gets flak for the awkward positioning of his female subjects, but in this case it works. Vlaakith’s pose reminds me of the contorted rigor mortis of Boris Karloff in The Mummy (and I’m happy Reynolds resisted the urge to make a ‘sexy undead’ – one of my pet peeves… female undead should be just as gross and gnarly as their male counterparts).

The cover for issue 105 is nostalgia heaven, plain and simple. Warduke was one of my favorite action figures growing up (him and Force Commander from the Micronauts ) so seeing him posing like he’s on the cover of an Iron Maiden album all but guaranteed I’d pick up a copy of the magazine. Reynolds not only does the venerable Warduke justice, he also gives him a few cycles of steroids – just in case your PC actually thought they could stand up to the ‘duke and survive.

Reynolds’ cover for Dungeon 124 is at a different scale than he typically works, and it’s so energetic and vibrant it makes me wish he would use it more (spoiler: he uses it for the final cover and its excellent). This painting is a perfect snapshot of what I picture when the PCs are squaring off against huge foes. There is a real cinematic quality to the action, and the spectral image of Kyuss rising in the background almost makes it look like a movie poster (just imagine – The Age of Worms saga featuring the voice of Benedict Cumberbatch as Kyuss!).

Marc Sasso invokes the blood soaked arena sands of a fantasy version of Rome for his cover of Dungeon 96. Sasso captures the high drama of the moment by keeping the viewer’s gaze in constant motion from one detail to the next: the gently falling roses foreshadowing the future spray of blood, the death motif of the armor, the grim look on the gladiator’s scarred face, and the telling inscription on the blade, ‘hate and kill’. Like Mark Zug’s bandit leader, this is the kind of painting that radiates personality and inspires player characters (and I’ve got the perfect miniature for it!), even if it wasn’t intended to.

I love the thick, colorful lines and painterly style of artist Chuck Lukacs, so I had to include his beholder in this list. While issue 97 was the only cover he made for the magazine, his illustrations festooned both Dungeon and Dragon during the 3e period (and because his style is so distinct, are easy to recognize), and helped to define the look of the era. I’ve never seen a beholder rendered quite like this before, and I really dig the almost globular treatment of the protruding eyestalks.

This issue was also a major milestone for the magazine: it contained Life’s Bazaar, the opening chapter of D&D’s first adventure path. The rest, as they say, is history.

Other than the iconic monsters of the game, no other image can singularly sum up the dungeons of D&D as well as the green devil portal from the adventure Tomb of Horrors. Artist Dave Studer gives Erol Otus’ classic illustration the sculptural treatment for the cover of issue 116 and it is simply amazing. One of the things I really liked about the 3e hard covers (especially the Monster Manuals) was their sculptural design. By drawing on that aesthetic, Studer visually reminds us that the entirety of the game’s editions are our playground and a source of inspiration. I’m not sure how big the original is, but I can’t help but think it would make a kick-ass door knocker for my house.

Artist Dan Scott never fails to impress me with the consistency with which he captures the spirit of adventure that defines D&D. This pair of Scott covers are perfect examples of that ability. Both capture an adventure in progress, and invite the viewer to fill in the story themselves – one of the highest achievements of fantasy illustration.

The cover of Dungeon 122 shows an elven rogue ambushed by lizardmen outside of their crumbling and vine choked, jungle temple. The great thing about this painting is how Scott tells the story through the use of his color palette. Aside from the violence, Scott’s choice of colors for the elf clearly mark him as an explorer and intruder while the naturalistically colored lizardmen are obviously native to this exotic land.

Scott tells the story of Dragotha the dracolich on issue 135 through the use scale. Again, the adventurer (a paladin this time) is clearly an intruder, only this time its David and Goliath retold. The adventurer is dwarfed not only by his opponent, but also by the massively pillared hall. Unless the paladin has some clever edge in this fight, the best he can hope for is a quick death.

As a side-note, while some might label the dracolich as one of D&D’s fringe monsters, I’ve always thought of it as part of the core brand. It was on the cover of both Pillars of Pentegarn, an endless quest book that helped draw me into the game, and Spellfire, one of the first D&D novels I read. It’s not surprising that I used a dracolich for my first real, recurring villain in the 2e game I ran in grade 8 and 9 (it lived in undermountain and its soul was eventually housed in a mechanical golem-like body).

The cover of Dungeon 146, by Tomas Giorello, is truly a beautiful painting and work of art. It wears its neoclassical inspiration on its sleeve, which isn’t a source you often see fantasy illustrators drawing from, and I love that. The sober colors, highly textural folds of fabric, and strong diagonal lines bring to mind David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps. Giorello’s work is so nice to look at it’s easy to forget the kraken tearing through the wreckage of a ship in pursuit of the pirate captain. It’s really a shame that Dungeon had stopped the practice of dedicating a page of the magazine over to an unadulterated version of the cover art, Giorello’s work deserves it.

Dungeon 150, the final print issue. Wayne Reynolds’ cover, depicting the climax of the final adventure path of the magazine, seems appropriately cathartic for the occasion of the magazine’s cancellation. For the epic fight against Demogorgon, prince of demons, Reynolds pulls together all of the ‘iconics’ that Paizo used during their stewardship of Dungeon as stand-in adventurers for covers and illustrations. It sums up the body of work very well, and the iconics’ steadfastness in the face of the suicidal melee assures fans of the magazine that Dungeon will not go out with a whimper, but with a bang (fortunately we all know how well everything turned out for Paizo).

Classic Monsters: Coffer Corpse

May 25, 2012Note: ‘Classic’ is a pretty subjective term, when I use it here I mean to say: monsters that have survived through the editions of D&D that I think are cool. In this series of articles I look at the development of a classic monster over time and try to add a ‘crunchy’ piece of my own to the creature’s canon.

I’m posting this second  installment of Classic Monsters as part of The Going Last Gaming Podcast’s May of the Dead blog carnival. There has been a shameful shortage of undead on Ménage à Monster, and the blog carnival seemed like the perfect opportunity to rectify that (and a great excuse to write another article in this series – the eye of the deep was getting pretty lonely).

installment of Classic Monsters as part of The Going Last Gaming Podcast’s May of the Dead blog carnival. There has been a shameful shortage of undead on Ménage à Monster, and the blog carnival seemed like the perfect opportunity to rectify that (and a great excuse to write another article in this series – the eye of the deep was getting pretty lonely).

I first encountered the coffer corpse lurking in the pages of the Fiend Folio and was instantly drawn to the fantastic Russ Nicholson illustration (click on the images to view full size). While the coffer corpse doesn’t get the same kind of fan recognition as the death knight (also introduced in Fiend Folio), I’ve always felt its low power level and unique mechanics gave it a certain charm. Like the Monster Manual’s vampire and mummy, the coffer corpse was also one of the few undead creatures in the game whose background jived with the mythology of the restless dead in horror films. While arguably a little obscure, the coffer corpse’s great mechanics, art and story combine to make the monster a classic.

Origins

Like many of the monsters in the Fiend Folio, the coffer corpse first saw print in the pages of White Dwarf as part of the ongoing Fiend Factory column (issue 8, 1978). In its infancy White Dwarf was a general gaming magazine with a focus on D&D, which makes sense given that Games Workshop (the company that produces the magazine) was at that time the UK distributer of the D&D game. Since the AD&D Monster Manual had only just been published in the UK, the creatures in the Fiend Factory column were created for the OD&D game.

Like many of the monsters in the Fiend Folio, the coffer corpse first saw print in the pages of White Dwarf as part of the ongoing Fiend Factory column (issue 8, 1978). In its infancy White Dwarf was a general gaming magazine with a focus on D&D, which makes sense given that Games Workshop (the company that produces the magazine) was at that time the UK distributer of the D&D game. Since the AD&D Monster Manual had only just been published in the UK, the creatures in the Fiend Factory column were created for the OD&D game.

The White Dwarf version of the coffer corpse sets out the parameters for all of the incarnations of the monster to follow. Cursed to undeath by incomplete or botched funeral rites (or as the author puts it, when a corpse fails to return to its ‘maker’), these animate corpses are often found floating on waylaid grave barges. The coffer corpse attacks by choking the life out of its victims, and can only be harmed by magic weapons (which inflict half damage). If the creature is struck with a normal weapon, it falls to the ground, apparently destroyed, only to rise up a round later in a display so horrible NPCs must succeed at a save vs. fear or flee in terror (the editor, Don Turnbull, notes at the end of the entry that this is probably an error and that PCs should also have to save vs. fear as well).

The coffer corpse was created by Simon Eaton, a name I’m not familiar with, as the only other credit I can find attributed to him is the witherweed (also featured in the Fiend Folio).

1st Edition

The coffer corpse was given an AD&D makeover for its inclusion in the Fiend Folio (and D&D canon). Its origins remained unchanged but a few of the monsters abilities were tweaked. Magic weapons do full damage to this version of the coffer corpse, and it falls to the ground if it is hit for 6 or more points of mundane weapon damage (instead of the ambiguous “if struck on the head” of the previous version). When the coffer corpse reanimates, all who are in melee must save vs. fear, not just NPCs. Additionally, the strangulation attack of the coffer corpse is upgraded from a simple 1d6 attack to one that inflicts automatic constriction damage each round, which is especially deadly since “nothing will release the grasp of the coffer corpse once it has locked its hands in place.”

2nd Edition

The coffer corpse next appears in 2e’s Fiend Folio Appendix for the Monstrous Compendium. While generally identical to its 1e incarnation, most of its abilities are expanded and explored in greater detail: this coffer corpse has resistance to some weapon types (magic slashing weapons inflict normal damage with no bonus, blunt weapons inflict full damage and piercing weapons inflict half damage), and it is possible to break free of its strangling grip (but with a strength of 20 it’s still very difficult).

The most important addition to the coffer corpse in 2e is an attempt to utilize the creature’s origins as a way for clever players to defeat it: “If the unfinished death ritual which binds the coffer corpse to undeath can be completed, the creature will be released and effectively destroyed.” The mechanics of how players might go about discovering and acting on this information is left to the DM’s discretion (and this bit is buried in the habitat/society section of the write-up), which is too bad since I think this is where the coffer corpse’s true potential as a classic monster lies.

3rd Edition

The coffer corpse never saw an official release for 3e. The Fiend Folio is generally regarded as a mixed bag and, in an effort to excise some of D&D’s sillier monsters from the game (the flumph is almost a clichéd example), many great monsters from this book, including the coffer corpse, were not updated for this edition of the game. However, Necromancer Games included the coffer corpse in their Tome of Horrors book, which updated just about every monster from 1e that WOTC had left behind (an admirable effort – though I think the carbuncle should have been abandoned to the dustbin of history). This version is more or less a direct translation of the coffer corpse from the Fiend Folio for 3e rules (damage reduction instead of immunity to normal weapons, and standard grab and constrict rules for the coffer corpse’s strangulation). It is a solid adaptation but, by sticking so closely to its 1e incarnation, I think it was a missed opportunity to expand and clarify the ‘unfinished funeral rite’ that the 2e version touched on (also, why they maintained the 25% chance for the coffer corpse to wield a weapon from previous editions is a mystery to me – the fact that the monster strangles people to death is what makes it interesting).

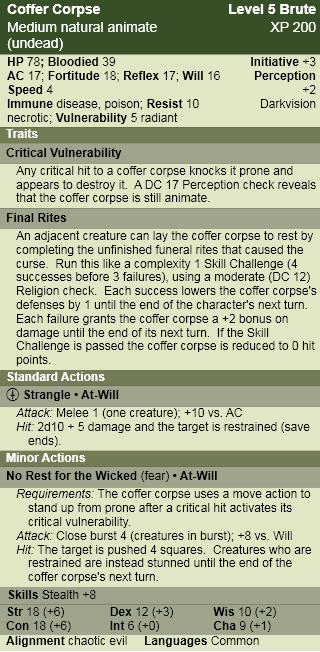

4th Edition

Not having a memorable appearance in 3e, and with 4e’s proliferation of low level skeleton and zombie breeds, it is hardly surprising the coffer corpse is absent from this edition. I do think that 4e’s skill challenge mechanic is particularly well suited to simulate the pitched struggle of a Cleric trying to complete funeral rites while the undead monster strangles her companion, which makes the coffer corpse the perfect candidate for entry into 4e’s canon.

Coffer Corpse

Barred entry into the afterlife by incomplete funeral rites, the coffer corpse is cursed to a restless eternity, its only desire to squeeze the hated spark of life from anything that crosses its path.

Lore

Religion DC 15: Although they superficially resemble zombies, coffer corpses aren’t animated through necromantic rituals, but are created as a result of a divine curse. Their deathlike grip is exceptionally strong, making escape all but impossible once the coffer corpse has wrapped its bony fingers around your throat.

Religion DC 20: Cursed by an incomplete funeral ritual, a coffer corpse is difficult to destroy, often springing back to life only moments after being felled. Only by completing the creature’s burial rites can the curse be lifted and the tortured soul granted peace.

Encounters

Coffer corpses can be encountered floating aimlessly in a waylaid funeral barge, slumped over a half dug grave, or lying in a coffin awaiting the completion of an interment ritual that never comes to pass. They are often part of a group of undead, created as part of the larger tragedy that interrupted the creature’s funeral.

Coffer Corpses in Combat

Every moment of existence is torture for a coffer corpse, so these undead monsters fight without regard for their own well-being. Even as they strangle and destroy they often liplessly whisper for release in their victim’s ear.

Pathfinder

For those looking for a classic interpretation of the coffer corpse, Necromancer Games has updated their 3e book Tome of Horrors Complete, and the coffer corpse, for the Pathfinder game (and since its part of the OGL you can get this version at the Pathfinder System Resource Document). If you like the ideas in my 4e version of the monster though, I have used it as the blueprint for this Pathfinder translation of the coffer corpse that builds on the creature’s 2e presentation. The flavour text and lore from the 4e monster are system neutral enough to be used as is.

Random Encounters: The Shackled City for Pathfinder (Chapter 1 Life’s Bazaar)

March 6, 2012Currently I am running a Pathfinder campaign for my group, and since I never got the chance to use my copy of The Shackled City hardcover while we were playing 3.5 I figured it wouldn’t be too much work to convert to ‘3.75’. In spite of Paizo’s claims of backwards compatibility, you can’t really use 3.5 D&D adventures off the shelf for Pathfinder. Most of it works, but the monsters and NPCs in particular are too weak to be a real challenge to a party of Pathfinder characters (I’m not worried about the traps, as The Shackled City has a reputation for the traps being a little too deadly anyway). Converting the stat blocks isn’t impossible, but it is a little bit of work, and since I’m doing the work anyway (I’m a bit of a stat block perfectionist) I thought I would share (click on the pictures at the end of the article to download PDFs of the updated stat blocks for all the monsters and NPCs as well as some additional handouts I created for the first chapter).

SPOILER ALERT

Obviously there are a ton of spoilers here, both for the campaign and the first adventure. So if you plan on playing in The Shackled City, peeking ahead is going to ruin a lot of the fun. If you are one of my players, it goes without saying that you shouldn’t read any further. You’ve been warned.

Greyhawk Gods in Pathfinder

Since my gaming group has had many previous adventures in the world of Greyhawk, it was important for me to keep the city of Cauldron in that setting. That meant using the Greyhawk deities that were the default for 3e D&D and rejecting the Golarion Gods of Pathfinder. However, the Gods in the Pathfinder Core Rulebook were each given 5 domains, rather than a number of domains based on deific power, as was the custom in 3.5. In order to bring the Greyhawk deities more in line with the Pathfinder rule set, the following list updates all the Greyhawk deities of core 3e with 5 domains each, except for Obad-Hai who always had six and Fharlanghn who I couldn’t find an appropriate fifth domain for. I used the official RPGA expanded domain lists for Living Greyhawk as a guideline, deviating in order to make sure that all the Pathfinder domains were covered.

- Heironeous: LG; Glory, Good, Law, Nobility, War

- Moradin: LG; Artifice, Earth, Good, Law, Protection

- Yondalla: LG; Community, Good, Law, Plant, Protection

- Ehlonna: NG; Air, Animal, Good, Plant, Sun

- Garl Glittergold: NG Community, Earth, Good, Protection, Trickery

- Pelor: NG; Glory, Good, Healing, Nobility, Sun

- Corellon Larethian: CG; Chaos, Good, Liberation, Magic, War

- Kord: CG; Chaos, Good, Luck, Nobility, Strength

- Wee Jas: LN; Charm, Death, Law, Magic, Repose

- St. Cuthbert: LN; Community, Destruction, Law, Protection, Strength

- Boccob: N; Artifice, Knowledge, Magic, Rune, Trickery

- Fharlanghn: N; Luck, Protection, Travel, Weather

- Obad-Hai: N; Air, Animal, Earth, Fire, Plant, Water

- Olidammara: CN; Chaos, Charm, Luck, Protection, Trickery

- Hextor: LE; Destruction, Evil, Law, Strength, War

- Nerull: NE; Darkness, Death, Evil, Water, Weather

- Vecna: NE; Darkness, Evil, Knowledge, Madness, Magic

- Erythnul: CE; Chaos, Evil, Madness, Trickery, War

- Gruumsh: CE; Chaos, Destruction, Evil, Strength, War

Life’s Bazaar

The following changes should be made to the adventure for it to play smoothly using the Pathfinder edition of D&D. Click on the pictures at the end of the article to download a PDF of Pathfinder stat blocks for every NPC and monster in the adventure (when I DM I like to have the monster stat blocks in front of me, instead of having to flip to the back of the book or shuffle through Bestiaries), as well as a few additional handouts useful to the adventure (Jenya Urikas’ list of abductions, Vervil Ashmantle’s letter to Kazmogen, the Cauldron coat of arms, and the first issue of Cauldron’s populist handbill – The Cauldron Crier).

Gear Door

Twilight mist trap; CR 1; type mechanical; Perception DC 21; Disable Device DC 20; Trigger touch; Reset none; Effect poison gas (twilight mist), multiple targets (all targets in a 10-ft.-square area).

Twilight Mist; type poison, inhaled; Save Fortitude DC 13; Frequency 1/round for 4 rounds; Effect 1d2 Dex damage; Cure 1 save

J4: Lurking Shadows

The challenge rating for most creatures has been reduced in Pathfinder, so to keep the adventure challenging and maintain the experience level, I increased the number of monsters.

Add an additional skulk in this room for a total of 3.

J11: Control Lever

I removed the Nystul’s undetectable aura on the bag of tricks. That spell is now covered by Pathfinder’s magic aura, but because of the slightly different mechanics for detecting and identifying magic items, concealing “the bag’s aura but not its magical nature” doesn’t make sense anymore. It is still just as dangerous for the party to find since it’s infected with the vanishing.

J17: Hall of Dancing Lights

Add an additional 2 skulks in this room for a total of 4.

J22: Theatre

The fine cloak in the chest has magic aura instead of Nystul’s magic aura. If detected, it radiates moderate transmutation (a character who casts identify or who uses Spellcraft to determine the function of the cloak must make a DC 14 Will save to pierce the illusion).

J26: Automaton Factory

I never really liked the raggamoffyn as a creature, and thankfully Paizo has never made a Pathfinder version of it. Rather than creating a new monster (when I wasn’t crazy about the original) just substitute a single adamantine cobra (included in the PDF) for the captured skulk and raggamoffyn (its poison and damage reduction will make it enough of a challenge).

J27: Gearworks

To simulate the pulverizer I used a clockwork servant and just gave it the ‘self-winding’ special quality (at the beginning of each encounter the clockwork creature winds itself as a swift action and carries out its last orders). It has a net instead of a sonic attack, but the battlefield control elements of the attack are very similar (and visually it can spit the net out of the same opening the pulverizer uses for its sonic attack).

J31: Alchemy Lab

Replace the raggamoffyn with an adamantine cobra.

J36: Great Factory

Since there isn’t a Pathfinder version of it (along with mind flayers and umber hulks), I replaced the grell with a grick. There are some pretty good Pathfinder versions of the grell online, but in the last 2 campaigns my group has played in they encountered quite a few grells, so I thought I’d give another creature a turn.

J40: Woodshop

Add an additional dark creeper for a total of 2.

J44: Hidden Foes

Add an additional dark creeper for a total of 2, plus the pulverizer.

J48: Secret Vault

I replaced the dread guard with an animated object, and styled it after an animated suit of metal armor. It is Medium sized instead of Small, but so is the dread guard.

J52: Kitchen

Add an additional dark creeper for a total of 3.

M3: Stony Greetings

I substituted a Medium earth elemental for the stone spike – it is slightly more powerful but has many of the same abilities.

M4: Major-Domo`s Quarters