Posts Tagged ‘Blather’

The Best Dragon Covers: 201-300

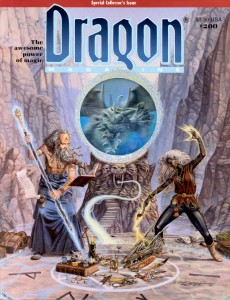

June 28, 2011As part of my ongoing celebration of Dragon Magazine’s 35th anniversary, I present the next instalment of covers, from issue 201 to 300.

These images represent quite a roller coaster ride through the ups and downs of Dungeons and Dragons. They bear witness to the development of the greatest settings the game has ever seen, the excesses and eventual decline of 2e, the demise of TSR, and the rebirth of the game in 3e under the ownership of Wizards of the Coast. Even though I had shifted to other games (namely Rifts) in the later days of 2e, I never strayed from Dragon (and even if I wasn’t in a campaign I always thought of D&D as my game). The writing, the ideas, and especially the art were always a great source of inspiration and entertainment.

I also liked the feeling of belonging to a community of gamers that came with the subscription. Yes that need has been fulfilled by the large (and vocal) gamer presence on the internet, but I don’t think anything will replace the visceral presence of a stack of physical artefacts (he says without irony while typing away on his blog – seriously, I can love my blog and the immediate and widespread distribution it has while still mythologizing the printed word, can’t I?).

One of the less positive aesthetic developments during this era was the inclusion of more text on the covers, obscuring the art. Fortunately, Dragon editors helped to mitigate this by publishing the cover art as a full page spread within the magazine. Since I’m focusing on the art of the magazine, I’ve chosen to reproduce those images and not the actual covers, even if it looks a bit strange not to see the familiar Dragon logo (as usual, click on the image for full size).

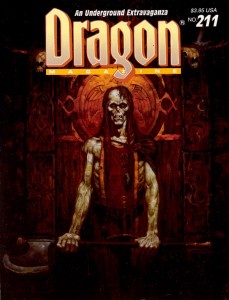

In the last article, I mentioned two of Brom’s fantastic Dark Sun images. He also painted a pair of covers for this run; two striking images of the undead. I always felt the first cover, for Dragon 211, was the perfect representation of a ju-ju zombie – an abomination created through life draining necromancy that retained some of its intelligence, could use weapons and had hard, leathery grey skin (and sadly hasn’t appeared in D&D since 2e). The halberd the creature wields also reminds me of old-school Citadel zombies (the ones armed with a cleaver-on-a-stick), which is a very good thing.

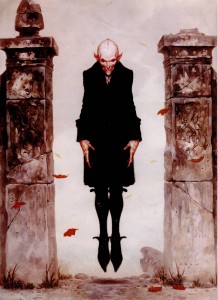

Brom’s second cover swings to the other side of the undead spectrum for Dragon 264, with a seriously creepy Nosferatu inspired vampire. Looking at the cover today, I continue to find Brom’s choice of vampire refreshing (in 1999 when this issue was published I was sick of Anne Rice copycats, today it’s the unmentionable ‘sparkly’ vampires of teen land). There is absolutely no question that Brom’s creation is a monster. With its rat-like teeth, beady eyes, and blotchy pinkish skin, the vampire is once again a living metaphor for the horrors of disease and the predatory nature of the aristocracy… not something to moon over and identify with.

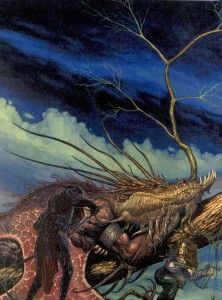

Another artist whose name should be familiar from the last article is Jeff Easley. Like the previous run, Easley was incredibly prolific in producing Dragon covers from 200-300, but these two are my favourite. Easley has painted a lot of dragons (I would say he is a master of the subject), but I think the cover to issue 225 stands out. Maybe it’s because I’ve got Caravaggio on the brain, but I love the dramatic impact of the dark, almost black tone. It really sucks you into the picture. Plus, I always appreciate it when an artist chooses to paint a dragon that doesn’t breathe fire. It’s a lot harder to visualize lightning breath, and as cool as King Ghidorah is, I’d rather have this as the go-to mental image whenever I think of blue dragons. Also, I’m not sure why undead and dragons go together, but apparently they do… and its unadulterated badassness.

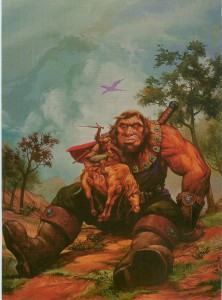

In tone, Easley’s cover for Dragon 254 is the polar opposite, and its naturalistic palette makes it seem almost like a landscape – which helps to suspend disbelief when you realize just how enormous that giant is. This cover echoes traditional fantasy renderings of giants which put into perspective just how small D&D giants are. I’ve never used a gargantua, or goriostro or similar sized monster in D&D, but I’ve always wanted to, and every time I look at this painting I feel like smacking myself for not designing that adventure yet.

There was a stretch during the middle of this run when every cover featured the magazine’s namesake. Now dragons are very cool (half of my favourite covers have them), but after a while it starts to get predictable (and if I recall, the letters column had some complaints about it). Fortunately, there are artists who can take any cliché and breathe new life into it. These covers still have the power to make me look at dragons in a different way.

R.K. Post is most well-known for his work setting the visual style for the Alternity game, but he also made several Dragon covers. The thing I love about his painting for issue 241 is how Post takes a well-travelled narrative (sneaking up on a sleeping dragon) and makes it as dark and full of twisted lines as his art. In this cover you cannot be sure of anything. The fighter in the foreground is cloaked in shadow, drawing a cruel looking blade. Is he the hero of this tale, or the villain? Instead of reclining on a bed of stolen riches, this dragon lays on a mighty tree, with which it blends seamlessly, like a creature of nature. It’s also nice to see a bard as part of the action, something you don’t often witness in D&D illustration.

If I could use a single word to describe Tony DiTerlizzi’s cover for Dragon 242 it would be ‘charming’. DiTerlizzi helped bring the Planescape setting to life with his incredible ink and watercolour pictures. Most of those were dark and sketchy, as suited the down and dirty flavour of Sigil, but here DiTerlizzi shows us he can also work with a lighter palette and more refined lines. It’s also full of whimsical little details that ensure I’ll never get bored of looking at it – the dice on top of the D&D books, the strange orrery, and especially the dragon’s tiny spectacles. This painting helps to remind me that dragons aren’t just dumb brutes there to blindly rip apart adventurers. They are some of the most intelligent creatures in the game, have their own goals, and just maybe, indulge in the occasional game of chess.

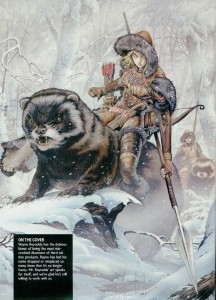

The next pair of covers each feature paintings with interesting mounts and riders. I’ve never had the chance to play a character with a special mount (I’m usually the DM for our gaming group), but these pictures hold enough inspiration that I feel left out.

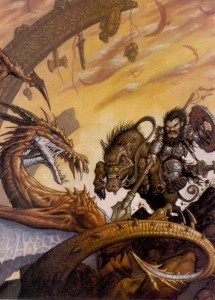

Matt Wilson is now the co-owner of Privateer Press, but in the nineties he did a bit of work for TSR, including this cover for Dragon 245. Dwarves aren’t one of those fantasy races you usually associate with cavalry, but once you see a dwarf knight on a razor tusked boar pulling a St. George, you know it’s right. Looking at this painting today, I also find it interesting to see the proto-vision of the style that would one day be associated with the Warmachine game.

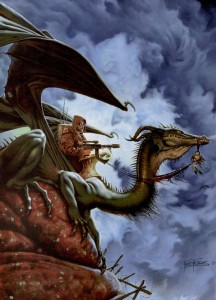

I mentioned veteran Dragon artist Fred Fields last article, and you can see how much his style changed over the years from Frazetta-like heroic fantasy to a gritty photo-realistic one. When Dragon 248 came out (1998), I was playing a lot of Rifts, so I had a natural inclination to like the genre crossing for its cover (the goggles, for flying without a canopy are a nice touch). Of course in Rifts you can be a dragon, so my friends and I would joke that the guy with the machine gun was actually the dragon’s familiar.

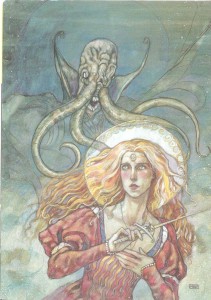

I know a lot of people hate them, but I have always loved psionics in D&D (yes, even in 2e when they were obviously broken, but who didn’t love rolling for wild talents?). One of my favourite issues of Dragon covering the subject was 255, with a stunning watercolour cover by Rebecca Guay (I liked the issue so much it’s the only time I ever wrote to the magazine – and I had my letter published in 259!). I love the almost medieval look of her lines, and the light washes of paint make the image look ethereal – perfect qualities to depict a psionic struggle between heroine and mind flayer. This battle could easily be taking place in the physical world, the mental plane, or a blending of our perceptions of the two.

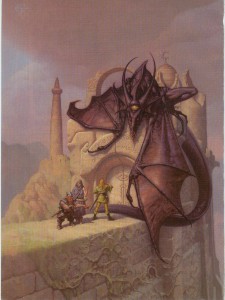

I was ignorant or Mark Zug’s work until I looked up the artist of these two long-time favourite Dragon covers. Besides depicting an awesome bat-creature acting as a guardian of a magically sealed doorway, Zug’s cover for Dragon 271 also contains a hidden message spelled out in those runes. I’ve never figured out what it says, but I like knowing that there’s a mystery to be solved. It’s this kind of Easter egg that moves a painting from being a fantasy illustration to a specifically D&D one.

Nothing signifies the transition to 3e more than this cover for Dragon 275. Yes, the magazine had switched over to the new edition in the previous issue, but Zug’s painting of a noble half-orc paladin summed up the shift in the game’s philosophy without words – no more boundaries.

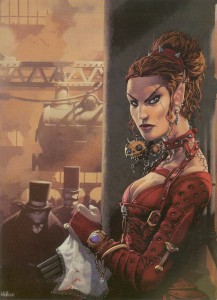

There is so much to dig about Kev Walker’s cover for Dragon 277, the multi-barrelled pistol concealed under a lace handkerchief, a badass elf in studded leather, locomotives, Victorian fog, and you have to love that half-orc with the righteous mutton chops in the background. If you have ever wanted to play a steampunk version of D&D, this painting is it.

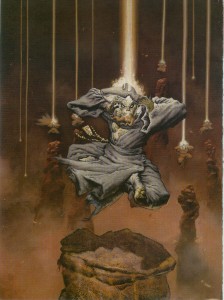

I mentioned my love for psionics, so it’s no surprise that I included Paolo Parente’s cover for Dragon 281 in this list. It’s doubly hard to make a visual representation of mental power, both because psionics by their nature, have far few optical effects than traditional magic, and also because there isn’t a deep well of reference material for artists to plumb. Parente takes these limitations and grinds them into the ground. This picture of a group of Githzerai in meditation (as well as Rebecca Guay’s), present the best argument for the place of psionics in a fantasy setting.

The rise of 3e is also the rise of artist Wayne Reynolds. Like Brom with Dark Sun, WAR (as he signs his pieces) was responsible for the visual style of Eberron (and with all the covers and large color illustrations he did for other 3e products, it could be argued he helped define the style of the edition itself). No run of Dragon covers that includes 3e material could be complete without a WAR painting. His work always has a dynamic sense of action that really energizes me and makes me want to start rolling dice now. I also like this piece for the things it doesn’t include: ‘boob windows’ (to use Wundergeek’s term) and adventure inappropriate clothing – art crimes WAR has definitely been guilty of in his body of work.

In the next instalment I’ll look at the bittersweet final years of Dragon.

The Best Dragon Covers: 101-200

June 15, 2011This month Dragon magazine reaches two milestones: its 400th issue and its 35th anniversary. To celebrate, they’re looking back on the magazine’s storied history and the WOTC website has created an online gallery featuring the cover art of Dragon’s first 100 issues. The covers of Dragon are a great source of gaming inspiration, and feature some of the best talent in fantasy illustration. The art was so good that TSR often reused it in its other products (which drew its share of criticism but never bothered me – it made me feel like an ‘insider’ when I recognized a painting from Dragon). For me the covers also signify something in addition to great art. My interest in Dragon magazine grew as I made the transition from player to dungeon master, developing into a very long subscription and culminating in what some would call an obsession (well, anyone who’s seen the boxes of magazines on my book shelves).

There are some excellent covers in those first 100 issues (seriously, check them out now), including Denis Beauvais’ incredible series of chess themed paintings (probably my all-time favourites), but I missed out on most of them. The very first issue of Dragon that I owned was number 87, indefinitely borrowed from my school library (don’t tell Baythorn Public School). Sure, later I acquired many pre-100 issues, but it wasn’t quite the same. I read the back issues with the eyes of a collector. When my monthly copy of Dragon came in the mail though, I absolutely devoured every page. And when I wasn’t reading, those covers stared up at me from my pile of gaming books spread across my mom’s kitchen table.

So I’m joining the celebration and over the next couple of weeks I’ll showcase some of the magazine’s stand-out covers – post issue 100. These are images that for one reason or another have stuck with me over the years, and flipping through my collection today they still have an emotional impact. It was nice to have the excuse to get reacquainted with some old friends (as usual, click on the pictures to see them full size).

Issue 116 featured an amazing scratch-built model of a red dragon by Peter Botsis. I really love the combination of miniature painting and smoke effects – the three-dimensionality somehow makes it seem more real to me than a traditional painting. It took me a decade and a half of waiting, but in University I was finally able to combine dry ice and miniatures for my own tabletop game (thanks to a friend who works at a lab) – although instead of dragon smoke it simulated the fetid miasma of the Hive for a Planescape campaign.

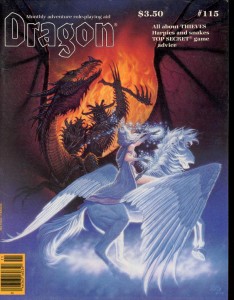

The cover of issue 115, the Antagonists by Denis Beauvais (of the chess covers) is truly a classic. Many of his covers featured the struggle between good and evil, but what I love about this painting is how the composition engages the viewer by putting them on the side of light, confronting the demonic forces of darkness face to face (almost daring you to open the cover and face the dangers within). I’m pretty sure that’s the first time I ever saw bladed wolverine style armguards as well, a look that surely influenced artists like Brom and Wayne Reynolds. Oh, and it was so badass that Ral Partha immortalized it in miniature form.

A frost giant skeleton bursting out of a snow bank hardly seems subtle, but my favourite parts of the cover of issue 126 by Daniel Horne are the small details that move your eye around the page and tell a story without words. The skeleton’s missing finger, the sword lodged in its armour, the ineffectual scattering of arrows, the empty quiver, and finally, if you look very closely, you can see that the last arrow gives off a slight glow… an arrow of undead slaying perhaps? It’s also nice to see a female character dressed appropriately for adventuring.

Dragon 127 and 129 are both Keith Parkinson paintings and both were reused in more than one TSR product (the Big Stash – the one with the dwarves, I remember being included in a Forgotten Realms calendar I got for my birthday when I was a kid). Parkinson was a master of atmosphere and the paintings’ multiple appearances are a testament to that. With his painterly style and slice of life (fantasy life that is) subject matter you can’t help but be drawn into the D&D game world with these covers.

I’ve mentioned before how much I like Jeff Easley’s dragons, but the cover of Dragon 138 shows that he can do just as well depicting the undead. I really dig the earthy palette of this painting – it reminds me of a freshly churned grave (in true horror movie style with a rotting up-thrust hand of course). Dragon’s October issues had a long tradition of following a Halloween theme, and I always looked forward to them.

Fred Fields did a lot of work for TSR, but this cover for Dragon 142 stands out for two reasons. The first is purely nostalgic. This issue of Dragon marks the transition from 1e to 2e D&D. I was buying every issue in the local games store by then and it was soon after this that I got my subscription. The other reason I love this picture is that it represents a scene that every dungeon master has wanted to spring on his players, the classic ‘that hill you are sitting on is actually a dragon’ (which just beats out ‘that cave you walked into is actually a monster’s mouth’). I never managed to pull that one off, even though I set an adventure with a black dragon in a swamp shortly after this came out.

I enjoy the cover of Dragon 148 by Ned Dameron for similar sentimental reasons. This issue was awesome because it had a cardstock insert of the infamous magic item, the deck of many things. I immediately inserted it into the campaign I was running (totally disrupting it with excessive amounts of magic) and that meant keeping this issue on hand. There’s something to be said of the hard bitten everyman adventurer of old school art, but to a scrawny kid getting ready to enter high school for the first time, these were the kind of larger than life demigods that I wanted to play (I rooted for the guy with the Morningstar, since I thought he was a thief, and they were my favourite class).

It might be the sense of dread evoked by the sickly green glow reflecting off of the bugbears’ scales (actually I’m not exactly sure what they are, but I always assumed they were bugbears because of their ears and sneaky disposition), but it’s probably just the expression on the little bastard’s face in the bottom right corner that makes me love this cover for Dragon 152 by Paul Jaquays. When I was a kid, I played with a guy whose character was always running off and trying to steal all the treasure. I wanted him to get his just desserts, like the subject of this painting.

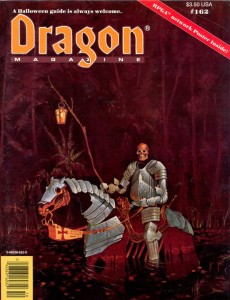

There’s not more of a reason why I like the cover of Dragon 154 by Bob Eggleton other than I think it looks like an awesome monster combination. Earthtones and undead definitely feel right together… A theme picked up by Michael Weaver for Dragon 162 (surprise, another Halloween issue). The more I stare at this painting the more I feel haunted. The hollow, rusted armour, the emotionless disembodied head, the lonely fall colouration – for some reason it all reminds me of the ravine near my mother’s house (not that its filled with the restless dead, it’s just that certain parts of the ravine had a definite character that I see in this cover).

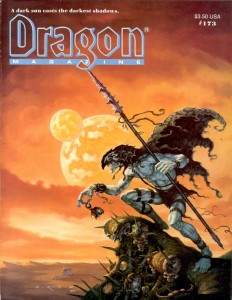

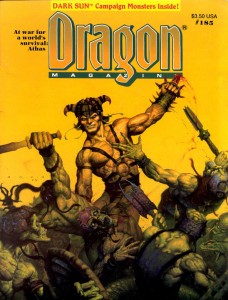

Gerald Brom’s unique paintings captured the brutal savagery of Frank Frazetta and infused them with a dark edge that twisted everything into an alien form – a style that was absolutely perfect for the Dark Sun setting. In fact, Brom’s style is so synonymous with Dark Sun that Wayne Reynolds paid obvious tribute to his work with the covers of the 4e revamp of the game world. Brom made two Dark Sun themed covers for Dragon, issues 173 and 185. The first issue, with the belgoi, had me sold on Athas, and I bought the boxed set soon after. Brom’s work was also immortalized by Ral Partha, although they used the belgoi as a model for their gith shaman.

Larry Elmore is one of the giants of fantasy illustration, and he painted a lot of covers for Dragon magazine, but looking back through my collection I have to admit that most of them didn’t really jump out at me as exceptional (unlike his product and book covers for which his reputation is well deserved). Most of Elmore’s covers were just pretty women standing idly in front of a scenic backdrop. They were well executed technically, but they didn’t inflame my imagination. Unlike those paintings, the cover of Dragon 200 lives up to Elmore’s exceptional Dragonlance work… plus it had a hologram (in the eighties if you wanted to jazz something up you made it glow-in-the-dark, in the nineties it was holograms).

In the next instalment I’ll look at Dragon’s covers post 200.

Citadel Combat Cards and the Golden Age of Miniatures

May 31, 2011Monster miniatures are one of those subjects that I‘ve been meaning to write about for a while, but much like my painting schedule (I think I just might be the world’s slowest painter), I haven’t gotten around to it (until now). I really got into miniatures around the same time that I graduated from playing a henchman in my older brothers’ D&D games and started running games for my friends. So owning and painting minis will always be intertwined in my mind with the idea of being a dungeonmaster. Coincidentally, this is also when Citadel adopted the ‘slotted base’ and moved from a pure 25mm scale to the larger 28mm size (both changes which today are industry standards).

I’m not sure what it was about those early miniatures that clicked so deeply with me. Maybe it was the John Blanche and Ian Miller artwork which Fighting Fantasy books had already planted in my mind. Maybe it was the way Citadel was changing miniature design. Everyone’s opinion on the ‘golden age’ of anything is subjective, but for me this was the golden age of miniatures. I know objectively that sculpting techniques and advances in materials have made unquestionably better miniatures over the years, but much like the first James Bond movie that you see indelibly marks you with an opinion on the ‘best Bond’, nothing will replace those Citadel miniatures from the late 80’s and early 90’s for me (yes, I even like ‘beaky’ space marines).

Whenever I had the money, I would pick up a blister pack, or split one with my friends (minis were a lot cheaper back then – if I were a kid now I don’t think getting into miniatures on my family’s budget would be possible). I started collecting White Dwarf magazine, even though at that time it covered only Games Workshop games. I poured over the painting and modelling advice and the ‘eavy metal section of photographed miniatures (the artwork kicked ass too). For Christmas one year I got a copy of Advanced Heroquest, and my friends and I played the hell out of it (I still have many of those plastic skaven); I played a little epic scale Warhammer 40,000, but I wouldn’t have even known those games existed if it hadn’t been for White Dwarf.

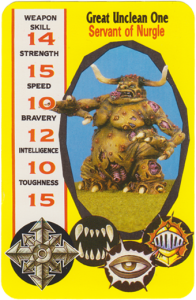

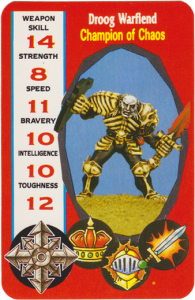

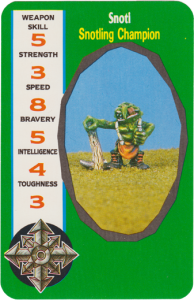

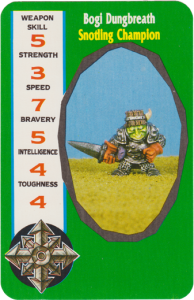

Somewhere in that mix I came across Citadel Combat Cards. As a game, there really wasn’t much to the cards. They were basically another version of war, or top trumps – if you were bored they were good to kill a half an hour with your little brother but that was about it. But the pictures on the cards were the main attraction. They featured photos of the ‘greatest hits’ of the citadel miniatures line. Like ‘eavy metal in White Dwarf, the pictures on these cards opened my eyes to the potential miniatures held – they could be works of art in themselves and the choices you made as a painter could completely alter the personality of the finished product. They also became something of a wishlist for miniatures I wanted to own. Even now, when I have far too much unpainted lead (enough to enrage my partner), if I see one these miniatures listed on ebay, it’s hard not to scream “It must be mine!”

Now I lost my collection (Chaos, Dwarf, Goblinoid, Monster and Warrior) of Combat Cards years ago, and since then I’ve been looking for a scan of them on the internet (they are long out of print and far too expensive to pick up on resale). Enter Ben from the blog Darkly Through Glass to answer my muttered oaths. Besides being a nice guy, he’s also been scanning his (amazingly pristine) sets of Combat Cards and posting the digital copies for the benefit of nostalgia obsessed souls like me (his download page is here).

I have a pretty good memory of the cards, but actually being able to flip through them once again really took me back (and more importantly made me vow to pick up my brush more often). You should check them out for yourself, but here are a few of my favourites (click for full size):

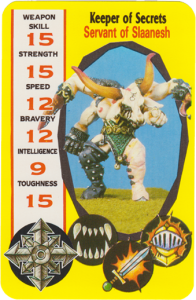

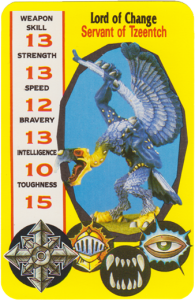

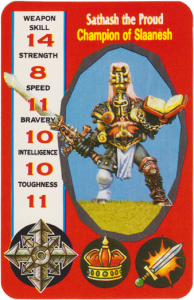

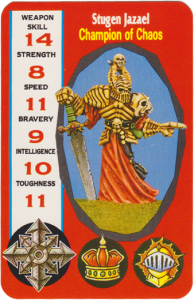

Ah, the unholy quartet of Chaos. In high school I was absolutely obsessed with the Realm of Chaos stuff, especially the art of Ian Miller who I desperately tried to emulate (ripe fodder for another post). I’ve also always wanted a complete set of the 4 greater daemons. It’s only taken me two decades but I’ve only got one more to go – for some reason old-style bloodthirsters are in much higher demand than the others (and a little out of the reasonable price range).

More Chaos. Many years ago, without knowing the Combat Card connection, Sathash was the first miniature my partner ever got for me (is there a better sign of true love?). I stole the look of Stugen and Droog in their bone armour for my depiction of Hedrack when I ran the Temple of Elemental Evil (and its 3rd edition sequel Return to the Temple of Elemental Evil).

Finally, I’m pretty sure that Snoti and Bogi here are the reason for my love of annoying little goblinoids and imps (probably the Wormy comic as well) to torment my players with (as helpers, enemy familiars, messengers, even a loan officer in Planescape).

Update

Ben has moved to a new blog, Fantasy3D and has completed the scans of all the original Citadel Combat Card decks, which can be found on his download page here.

Random Encounters: Put on a Grey Ribbon

May 21, 2011 Thanks to myths and monsters week on Daily Planet, I discovered that May is Zombie Awareness month. According to the Zombie Research Society (who I guess are the ones who decided this… I wonder if they have a government grant?), the month of May was chosen because:

Thanks to myths and monsters week on Daily Planet, I discovered that May is Zombie Awareness month. According to the Zombie Research Society (who I guess are the ones who decided this… I wonder if they have a government grant?), the month of May was chosen because:

“Many films important to the evolution of the modern zombie are set in the month of May, from the original Night of the Living Dead, 1968, to the well received Dawn of The Dead remake of 2004. Also, because spring naturally brings with it a sense of renewal and hopefulness, May is the perfect month to emphasize continued vigilance in the face of the coming zombie pandemic.”

Well, as the picture can attest to (circa the 2008 Toronto Zombie Walk); I’m certainly not unaware of the coming zombie apocalypse (in the future, undead Canadians will look at me dressed up in that picture and be offended). And even though I’ve never really talked about the undead on this blog (hey, where’s the underwater beholder awareness month?), they are an important ingredient to any ménage à monster.

That said, zombie awareness month actually got me thinking about something else – fake undead (maybe it was the photo). During the days of 1st edition D&D (and bleeding over into 2nd), there was a popular trend of ‘gotcha’ monster design. That is, monsters that look like something they are not to trick adventurers into using ineffective tactics against them. The best example of this is probably the gas spore – a monster that looked just like a beholder, but exploded in a cloud of deadly spores if you panicked and hit it with a weapon (I happen to like the gas spore – but it probably has more to do with nostalgia and the sweet Trampier illustration than good design), but it was by no means the only one. That’s where the fake undead come in. These were a category of gotcha monsters that looked like undead (and sometimes acted like it too)… but weren’t. So while your party’s cleric was busy wasting time trying to turn undead, it was killing the rest of you in some non-undead way.

Now some people like using this kind of monster, and maybe I’ve been brainwashed by post 3rd edition thinking, but these creatures just strike me as cheesy one-shot adversaries designed solely to exploit the game’s mechanical assumptions. But complaining about the design choices of monsters from the dustbin of D&D’s history doesn’t get us anywhere. If Zak from Playing D&D with Pornstars can rehabilitate the gas spore, then perhaps some of D&D’s fake undead can be salvaged as well:

- Adherer (from Fiend Folio): This humanoid was covered in loose folds of flesh that made it look like a mummy. It secreted glue from its skin that made your weapons stick to it (I actually did use this monster in 2e, more for its sticky power than its resemblance to a mummy). Surprisingly, this monster has already been rehabilitated – by Paizo in their book Misfit Monsters Redeemed. Here they are presented as living relics of a horrible experiment conducted by phase spiders on the ethereal plane.

- Drelb (Monster Manual II): A creature native to the plane of negative energy that looks like a wraith, and is summoned to guard an area or treasure. It cannot be turned, but tricks clerics who try to do so by appearing to move away, but actually shrinks and moves forward. The drelb’s special power is as lame a

s a monster that attacks by pretending its going down a flight of stairs. To rehabilitate it I’d get rid of the shrinking thing and quit making it imitate wraiths. Now it’s a malevolent blot of pure necrotic energy that can only manifest in the zone it was summoned to protect (using a mechanic like 4e homunculi). To keep its anti-clerical theme it could do something bad (like an attack or imposing a condition) to anyone who used a power in its aura with the radiant keyword (or someone who used a healing power instead).

s a monster that attacks by pretending its going down a flight of stairs. To rehabilitate it I’d get rid of the shrinking thing and quit making it imitate wraiths. Now it’s a malevolent blot of pure necrotic energy that can only manifest in the zone it was summoned to protect (using a mechanic like 4e homunculi). To keep its anti-clerical theme it could do something bad (like an attack or imposing a condition) to anyone who used a power in its aura with the radiant keyword (or someone who used a healing power instead). - Gambado (from Fiend Folio): This one-legged creature uses a discarded skull as a head prosthetic, digs a hole in the ground, and when some adventurer comes to investigate the skull, it jumps out at them. I’m amazed this thing survived two editions of the game. I’d take away the ambush predator aspect of this monster and instead focus on the bone stealing and collecting. Reimagined, it becomes a sort of necromantic caddisfly that forms a cocoon out of bones. It can animate its grisly shell to move around the battlefield and attack. Perhaps absorbing new bones heals it, or maybe the gambado grows weaker as its protective cocoon is shattered (yes the name comes from ‘leaping and springing’, I guess it could leap out at you and try to bite your face off it its cocoon is destroyed).

- Necrophidius (from Fiend Folio) and Yellow Musk Zombie (from Monster Manual II): OK, neither one of these monsters really needs to be rehabilitated. With the addition of knowledge checks to the game in 3e, these go from gotcha to cool. Construct made out of snake bones that can hypnotize you by swaying back and forth? Awesome. Killer plant that controls you by planting a seed in your head? Even more awesome. I’m willing to admit when my idea falls apart.

- Pseudo-Undead (from Monster Manual II): The worst culprits of the lot, pseudo-undead are humanoids that look like undead, but have none of their special abilities. Like a Scooby-Doo villain, they spend their pathetic lives hoping others will be too scared to attack them. Here’s a tidbit: “Pseudowraiths and pseudospectres cannot fly but walk so lightly as to leave no trace, and are often thought (unless closely observed) to be floating above the surface, although this is an illusion.” Like the gambado, this is going to take a bit of a stretch. First I’d call the creature something different, like a necroclone. Then, taking a bit of inspiration from the myrmarachne melanotarsa, the monster becomes a shapeshifter with a taste for rotting, undead flesh. It can mimic corporeal undead so fully (and is resistant to disease and necrotic damage) that it lives among colonies of ghouls, and packs of zombies. These are not only the necroclone’s preferred food source, but they also provide the monster with protection, since few other monsters would target a large group of dangerous undead.

That covers 1e’s core monster books, but I’m sure later supplements, as well as Dragon and White Dwarf, hold more examples. Maybe someday I’ll even get around to statting these beasts up.

Classic Monsters: Eye of the Deep

May 13, 2011Note: ‘Classic’ is a pretty subjective term, and when I use it here I mean to say: monsters that have survived through the editions of D&D that I think are cool. In this series of articles I look at the development of a classic monster over time and try to add a ‘crunchy’ piece of my own to the creature’s canon.

The eye of the deep, the beholder’s unloved cousin, has long held a special fascination for me. As I’ve mentioned previously, when I was a kid who didn’t know any better, flipping through my older brother’s copy of the Monster Manual, this critter caught my eye. Until I had been playing the game for some time, I mistakenly believed that the eye of the deep was a more powerful version of the beholder, since it had eye rays and giant lobster claws (lobster claws were the tentacles of the eighties). Even when I had been properly schooled in D&D lore, my initial impressions of this monster insured it would regularly surface from my subconscious any time I found myself staring down into water that was too deep to see the bottom (well, the eye of the deep and those giant tube worms from the G.I. Joe episodes with the MASS device).

The eye of the deep, the beholder’s unloved cousin, has long held a special fascination for me. As I’ve mentioned previously, when I was a kid who didn’t know any better, flipping through my older brother’s copy of the Monster Manual, this critter caught my eye. Until I had been playing the game for some time, I mistakenly believed that the eye of the deep was a more powerful version of the beholder, since it had eye rays and giant lobster claws (lobster claws were the tentacles of the eighties). Even when I had been properly schooled in D&D lore, my initial impressions of this monster insured it would regularly surface from my subconscious any time I found myself staring down into water that was too deep to see the bottom (well, the eye of the deep and those giant tube worms from the G.I. Joe episodes with the MASS device).

I admit, I’ve never used the eye of the deep in a game. I’m not really sure why. It could have been because I’ve never ran a game that focused on water encounters. Or it could be because(as far as I’m aware), the eye of the deep was never used in a single published adventure, not even in 2nd edition’s monstrous arcana series focused on beholders and beholder-kin (Eye of Pain, Eye of Doom, and Eye to Eye). Then again, it took until 3.5 edition for me to use a regular beholder in an encounter (and no one would argue with its icon status), so I hardly think that’s a strike against it.

Possible Origins?

This is a bit of a non sequitur in an already long article, but I’ve always wondered if the character of Alpha Centauri from Doctor Who had anything to do with the inspiration for the eye of the deep. It does resemble the creature, and it did air in the Curse of Peladon serial in 1972, 5 years before the eye’s appearance in D&D.

1st Edition

While the beholder made its debut in the pages of the Greyhawk supplement for OD&D, the eye of the deep didn’t make it into the game until 1977’s Monster Manual. It has the distinction of being the very first in a long line of beholder variants the game acquired over the years. The book establishes the eye of the deep as a 3-5 foot diameter sphere (size large in AD&D), with a pair of crab-like pincers, a large central eye and a pair of eyestalks. The main eye can emit a blinding flash that stuns opponents, while the smaller eyes can work together to create illusions or cast hold monster and hold person independently.

In Dragon Magazine’s The Ecology of the Eye of the Deep, none other than Ed Greenwood expands on the creature’s lore. The meat of the article describes the creature’s reproductive cycle (they’re hermaphrodites), its hunting habits (it uses its illusion powers to lure prey close and then stuns them with its central eye), and even scientific tidbits about its physiology (the eye of the deep cannot rise to the surface without the change in pressure causing it to explode). Greenwood also adds to the eye of the deep’s attacks, giving it the ability to grab onto opponents with its claws.

2nd Edition

2nd Edition

The eye of the deep next appears in 2nd edition D&D’s first volume of the Monstrous Compendium. Here it is presented as a variant of the beholder, but is otherwise almost identical to its AD&D version (although its size remains 3-5 feet in diameter, in this version of the game that makes it a small-medium size creature). Ed Greenwood’s grasping claw attack is not incorporated into the monster’s statistic block.

Late in the edition’s lifespan we are given another glimpse of the eye of the deep in the monstrous arcana supplement, I Tyrant. Although the creature gets only a short paragraph in the book, author Aaron Allston gives us a glimpse of the eye of the deep’s sociology: they communicate over long distances using the light flash from their central eye, and teach their offspring how to hunt using their ability to generate illusions (although this doesn’t really fit with Greenwood’s depiction of them randomly leaving eggs on the sea floor).

3rd Edition

The eye of the deep isn’t updated until 3.5 edition’s Lords of Madness hardcover. In this incarnation the eye retains the ability to stun and blind with its central eye, hold monster, generate illusions, and even grab hold with its claws. It loses the ability to hold person (which makes sense since hold monster supersedes that ability in this edition), but gains the power to project a cone of cold. This edition also sees the first real size change in the creature, growing to a nine foot diameter, 6000 pound behemoth (large sized with the option to advance in hit dice to huge size).

The eye of the deep isn’t updated until 3.5 edition’s Lords of Madness hardcover. In this incarnation the eye retains the ability to stun and blind with its central eye, hold monster, generate illusions, and even grab hold with its claws. It loses the ability to hold person (which makes sense since hold monster supersedes that ability in this edition), but gains the power to project a cone of cold. This edition also sees the first real size change in the creature, growing to a nine foot diameter, 6000 pound behemoth (large sized with the option to advance in hit dice to huge size).

The behaviour of the eye of the deep generally conforms to previous editions (it uses illusions to lure and confuse prey), but the authors (Richard Baker, James Jacobs and Steven Winter) made one alteration that I think illustrates the changing philosophy of D&D game design. Instead of keeping a solitary vigil over shipwrecks at the bottom of the ocean (and exploding if it ascends), the Lords of Madness eye of the deep prefers to hunt on the surface. While this approach may be less realistic (we are talking about a giant floating eye with claws) than Greenwood’s, it’s a change that puts the monster in immediate and direct conflict with the PCs and thus makes it much more useful for DMs.

4th Edition

It seems that the only legacy of this monster to penetrate the 4th edition of D&D has been the ‘eye of’ naming convention. Then again, the eye of the deep has not been singled out in its exclusion. It seems that the long list of beholder-kin from previous editions is one of the ‘sacred cows’ the designers of the game wished to slay. It seems though, that a long list of beholder variants isn’t what the designers had a problem with per se (the compendium currently holds 17 different variety of the monster). So I guess it was the specific variants themselves they didn’t like (some of them were pretty silly – I’m looking at you director)… Or maybe they just wanted to create something new. Regardless, I can’t let the snubbing of one of my favourite beasties stand, so I present to you this unofficial entry into 4th edition canon:

It seems that the only legacy of this monster to penetrate the 4th edition of D&D has been the ‘eye of’ naming convention. Then again, the eye of the deep has not been singled out in its exclusion. It seems that the long list of beholder-kin from previous editions is one of the ‘sacred cows’ the designers of the game wished to slay. It seems though, that a long list of beholder variants isn’t what the designers had a problem with per se (the compendium currently holds 17 different variety of the monster). So I guess it was the specific variants themselves they didn’t like (some of them were pretty silly – I’m looking at you director)… Or maybe they just wanted to create something new. Regardless, I can’t let the snubbing of one of my favourite beasties stand, so I present to you this unofficial entry into 4th edition canon:

Beholder Eye of the Deep

Not all beholders dwell in the twisted passages of the underdark. Some float in the lightless ocean depths, rising to the surface to terrorize and destroy any that dare cross their invisible territories.

Lore

Dungeoneering DC 15: Though they lack the sheer number of eye rays that other beholders possess, the eye of the deep compensates by way of strong grasping claws and the ability to generate illusions.

Encounters

Beholders are rarely willing to serve other creatures, and the eye of the deep is no exception. However, some eyes of the deep bully nearby sahuagin into servitude, using them as shock troops to subdue passing ships and coastal towns. The eye of the deep is a negligent master though, and over time the sahuagin invariably desert, fall in combat, or are eaten for food.

Eye of the Deep in Combat

The eye of the deep takes great pleasure in creating illusions to lure its prey in close. The cruel beasts create images of shipwreck survivors, mermaids, and anything else they think will draw their targets into the water. The eye of the deep always opens combat with a stunning blast of light from its central eye before ripping its helpless victim into digestible hunks with its claws.

Resume Transmission

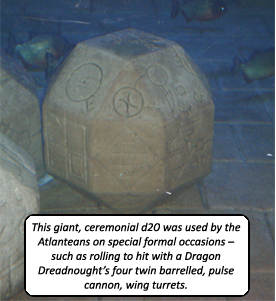

April 27, 2011 Wow, the last month has been a bit of a roller coaster ride. My crappy computer decided to give up the ghost (down), I spent a week cruising through the Bermuda triangle (way up – no Splugorth, but I did find a giant, Atlantean 20-sided die), and when I got home I found out the web host for this blog had gone out of business, erasing all my data in the process (way down)… I don’t like this ride, can I get off now please?

Wow, the last month has been a bit of a roller coaster ride. My crappy computer decided to give up the ghost (down), I spent a week cruising through the Bermuda triangle (way up – no Splugorth, but I did find a giant, Atlantean 20-sided die), and when I got home I found out the web host for this blog had gone out of business, erasing all my data in the process (way down)… I don’t like this ride, can I get off now please?

I think things are finally sorted out and I can resume regular posting again. I’ve got a brand spanking new computer thanks to the help of my more hardware savvy friends (it runs photoshop like a dream and more importantly, doesn’t sound like a jet engine taking off when you ask it to run anything more complicated than the calculator), I’ve got a new web host and I was able to reconstruct most of my old posts (I had to use text files, so unfortunately I’ve lost all the old comments and I couldn’t be bothered to recreate the scads of links – though I did remake the most important ones).

Anyway, what am I complaining about? I had a great vacation eating my weight in perfectly cooked steak, my batteries are recharged and now it’s time to make some monsters.

H.P. Lovecraft, Allan Moore and the Underdark

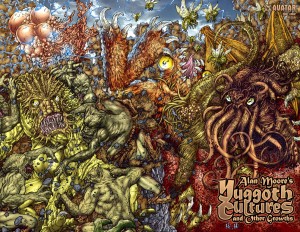

March 2, 2011I’m pretty late to the game when it comes to Yuggoth Cultures and Other Growths, by Allan Moore. It was released as a three issue comic in 2003 by Avatar Press, and I remember seeing it in the comic stores at the time, thinking it looked very cool, and then promptly forgot all about it. The issues were collected together and released as a trade paperback in 2006, and yet again I missed out. It wasn’t until last week that I stumbled onto a reference to the comic and so I finally checked it out.

The title is a allusion to H.P. Lovecraft’s Fungi from Yuggoth, his collection of 36 sonnets (I know Lovecraft has deific status amongst gamers and can do no wrong, but to tell you the truth I’m not really a big fan of his sonnets and poetry). Moore imagined himself as taking cuttings from those fungi (stealing ideas here and there if you will – but there’s no shame in that), and culturing them to see what could be grown. It’s a great metaphor, and in general it works. It reminded me of a concept album in comic book form – you might not like every song on the record, but you dig where the band was going with it.

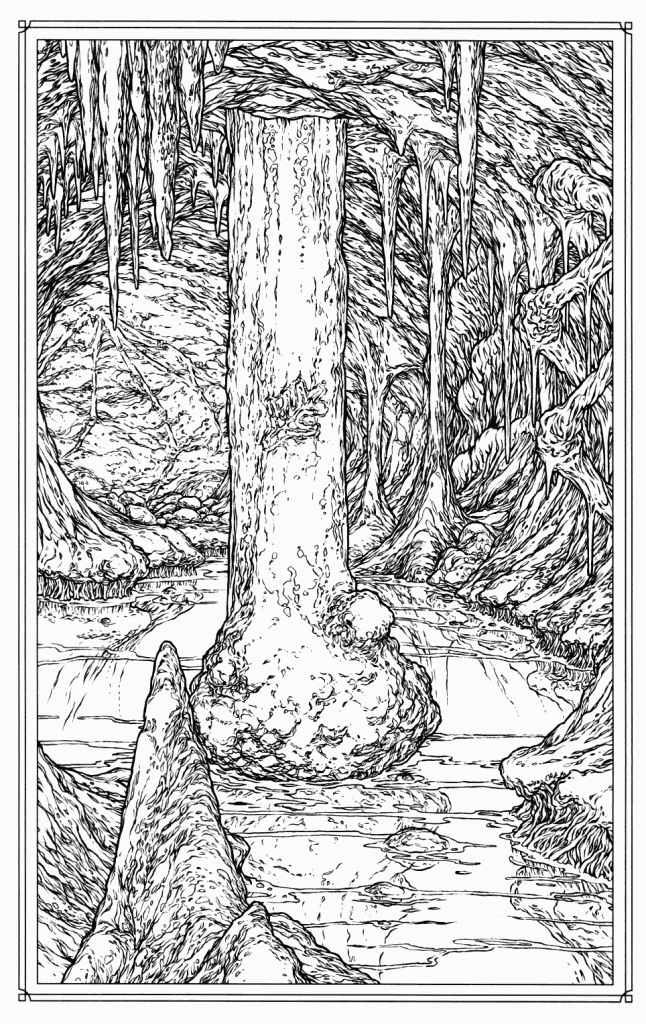

Just check Juan Jose Ryp’s wraparound cover (click on it for the full size)! The frenetic action, crazy colors and hyper detail are perfect for the madness inducing subject matter (I see Cthulhu, Nyarlathotep, a gug, a pack of ghouls, a flying polyp, and of course mi-go). As ideal as that picture is for a blog about monsters, it’s not the piece I wanted to write about.

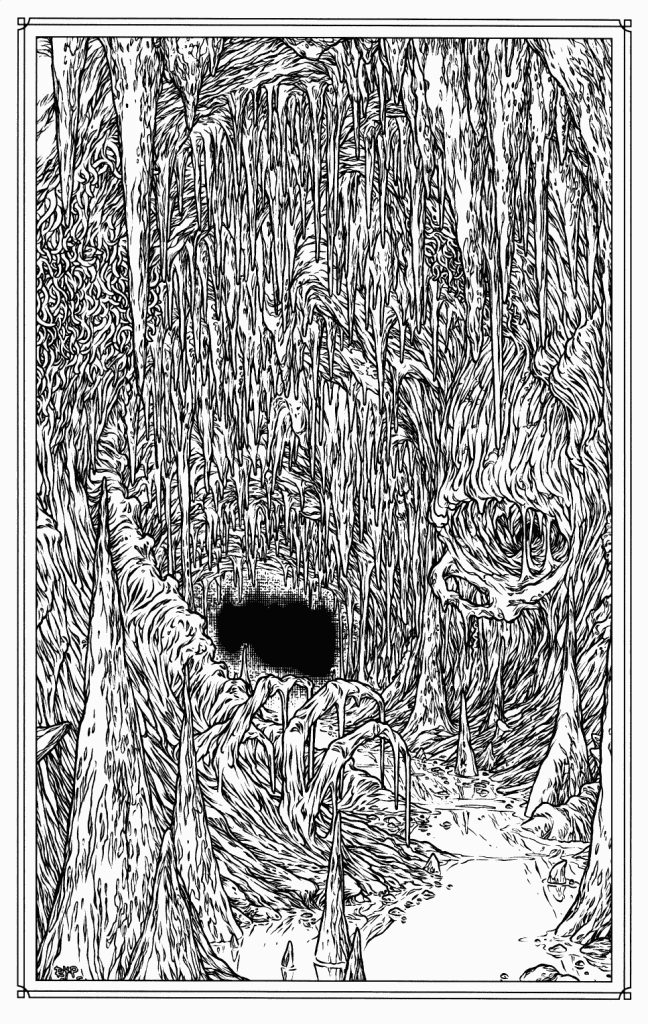

In the same issue Ryp also illustrates Moore’s poem, Zaman’s Hill, with two pieces that are the perfect representation of the underdark, maybe even the platonic ideal of the underdark (of which all other underdarks are shadows). My penchant for hyperbole aside, when I flipped to this page I was immediately struck by the thought, ‘so that’s what the underdark looks like’ (click on the pictures to see for yourself). And that’s a bit odd, since 25 years of D&D illustrations haven’t made me think that. Considering that the underdark plays such a huge role in the imagination of D&D, there are very few visual representations of it (there are many pictures of the creatures that live there though). That’s probably because there just aren’t that many landscapes in D&D illustration in general (even though Larry Elmore was clearly a master of the style). And that makes sense. Monsters are just more interesting (I am obsessed with them) and more immediate then the places which spawn them. But a great picture can transcend that generalization and I think that Ryp’s does.

In the D&D game I currently play in, my character the Jack of Clubs and his companions are working their way through a 4e adaptation of The Night Below boxed set. We’ve fought all manner of subterranean beasts (troglodytes, trolls, grell, and a behir) and I’ve never had trouble playing out those epic struggles in my mind. But when it comes to the underdark itself I feel as though my mind’s eye has formed only a crude backdrop against which our adventures play out. These pictures have changed that. My imagination is already filling those unsettling caverns with chanting Troglodytes, the maddening psionic hum of illithid mind-song, and the glittering trails of abolethic mucous chariots. The next time someone in your game wants to know what the underdark looks like, you have your answer.

But that’s not all. Yuggoth Cultures made me realize that the fungi’s spores are still spreading, sending out shoots and occasionally, twisting back together. Many of Lovecraft’s ideas are so pervasive in popular culture they sometimes come about full circle to meet each other face to face. Way back in Dragon 324 (when you could still hold the magazine in your hands) James Jacobs had a great article on Lovecraft’s influence on D&D where he specifically mentions the Lovecraftian influence on the creation of the underdark… and that’s how a pair of pictures in a comic completely unrelated to D&D come to perfectly represent one of the game’s greatest locales. Two mutant growths, sired from the same rhizome, but cultured in entirely different mediums, turn out to be twins.

The Goblin

February 18, 2011 Goblins are weak pathetic creatures that spend most of their short lives throwing themselves onto adventurers’ swords. It’s hard to argue with that, especially since goblins have always occupied the lowest rung of the monster ladder (just a smidge above kobolds) across all editions of Dungeons and Dragons (and given the influence of D&D, many other rpgs and computer games as well). Take a look at David Trampier’s goblin from the 1e Monster Manual. Don’t get me wrong, I like this picture (especially that clean pen and ink style of his), and the goblin seems a little threatening, but his facial expression almost makes him look worried – and he should be, he’s about to be magic missiled to death. After about third level, goblins become a joke. So much so, it’s even used to comic effect in Neverwinter Nights: Hordes of the Underdark (the joke being that you have to be reminded that to your average zero level schmoe, a goblin is still dangerous).

Goblins are weak pathetic creatures that spend most of their short lives throwing themselves onto adventurers’ swords. It’s hard to argue with that, especially since goblins have always occupied the lowest rung of the monster ladder (just a smidge above kobolds) across all editions of Dungeons and Dragons (and given the influence of D&D, many other rpgs and computer games as well). Take a look at David Trampier’s goblin from the 1e Monster Manual. Don’t get me wrong, I like this picture (especially that clean pen and ink style of his), and the goblin seems a little threatening, but his facial expression almost makes him look worried – and he should be, he’s about to be magic missiled to death. After about third level, goblins become a joke. So much so, it’s even used to comic effect in Neverwinter Nights: Hordes of the Underdark (the joke being that you have to be reminded that to your average zero level schmoe, a goblin is still dangerous).

Trampier’s goblin is good art, but it isn’t great art. For me, great art in an rpg has to either completely inspire you (sometimes suggesting an idea, or a snippet of a narrative that compels you to fill in the blanks), or blow your mind open to a new possibility. Incredibly enough, there is a picture of a goblin that does just that. Back during the 2e days, when my friend and I encountered the picture below (click on it to see it in its full glory!), it totally changed what we thought goblins could be in the game. It wasn’t a picture of a goblin, it quickly became the goblin.

A little history. I first encountered Sam Rakeland’s painting in 2e’s The Complete Book of Humanoids (although it was first used for basic D&D’s module cover, Assault on Raven’s Ruin). I have a lot of love for this book. Back in the day, using its rules, I played a misguided lawful good minotaur, my friend played an alaghi druid, and we even ran an adventure where everyone was a mongrelman living in the sewer. None of us ever played a goblin, but that picture made us fear them again.

All grown up (relatively), there’s a lot I could say about why I like this painting: the use of oils gives it a nice tactile quality, the dynamic pose directly threatens the viewer, the colors suggest the kind of cold, dark, hard bitten cave life I imagine goblins to have… but that’s academic. The savage ferocity of the creature made an immediate and indelible impression on my teenage self. It reminded me that goblins were monsters, not just 1-1 HD things that could inflict 1-6 hit points of damage. I mean look at that thing, I think your name level paladin just cowered behind his shield and crapped in his armor… from a goblin! It made such an impression, that any time we fought goblins afterward; we always wanted to know if we were tackling any old goblin, or the goblin. We never did fight the goblin, but I can’t say my characters really regretted that.

Looking at the digital paintings that grace the electronic pages of Dragon and Dungeon now, I wonder if there’s any room in D&D for this kind of illustration anymore. These days, art directors are very concerned with maintaining a certain look for all the creatures, to help maintain visual cohesiveness and develop D&D as a brand. This approach has some clear advantages to it, the most obvious being that everyone agrees on what a goblin looks like. It educates the audience to D&D’s visual language so that every picture doesn’t have to set out what a goblin looks like. The audience knows and you can just throw goblins into an action scene and the viewer still gets it. I hope that it also ensures we never see another illustration like the one for the salamander in 2e’s Monstrous Compendium (probably my most hated D&D illustration of all time). On the downside, it also leads to illustrations that have a sameness to them (something I’ve talked about before), and flattens out individual style. Maybe it’s because I’m old and jaded, or I’m too high on nostalgia, but flipping through Dragon (I guess ‘key-ing’ is more appropriate, but that’s another rant) I haven’t seen the likes of the goblin in a long time. And that’s too bad, because I think D&D needs great art, not just good, technically adept art that makes you think ‘cool’. It needs art that’s going to blow the minds of teenagers sitting around the kitchen table and leave them remembering the images until they’re old and jaded and complaining about the pictures in the tenth edition of the game.

Then again, maybe I’m getting too worked up about a painting of some 1-1 HD canon-fodder… just try telling that to the goblin.

Notes on the Artist

Far be it for me to wax hyperbolic about the painting without mentioning the artist, who it turns out is something of a mystery (in that he doesn’t really exist).

Sam Rakeland is credited in The Complete Book of Humanoids with the painting (and his signature is pretty clear), and according to the Pen and Paper RPG Database, he also did some other covers and interior pieces for TSR in the nineties, but then his work stops. I was a little disappointed, since I was hoping to see what he had been working on lately. In my quest to find some kind of gallery or homepage, I stumbled across the Internet Speculative Fiction Database, who list Sam Rakeland as a pseudonym of artist Rick Berry. I’m not familiar with Rick Berry but it turns out he’s a prolific cover artist and I’ve seen his work on bookstore shelves for the last twenty years. You can read more about him on his page here.

I can only imagine he used a pseudonym to keep his rpg and book cover work separate… maybe he was a longtime rpg fan and had always wanted to make some material for D&D, who knows? If anyone does know more, I’d love to hear.

Of course my teenage self couldn’t help pointing out to my adult self that he recognized great art, even when it was hidden behind a false name.

Lost Mojo

February 2, 2011 I seemed to have lost a little of my mojo last week. I’m not really sure why, but I guess if I knew then I wouldn’t have lost it would I? Premature February blahs maybe? If that’s the case let’s hope the groundhog has some good news. In any event, it’s nothing that a little Chop Suey can’t cure and get me moving again.

I seemed to have lost a little of my mojo last week. I’m not really sure why, but I guess if I knew then I wouldn’t have lost it would I? Premature February blahs maybe? If that’s the case let’s hope the groundhog has some good news. In any event, it’s nothing that a little Chop Suey can’t cure and get me moving again.

A random thought: I wonder what kind of groundhog day type rituals would exists in a fantasy world? It would have to be something that hibernates, since waking up early from hibernation would mean a short winter. For some reason I keep coming up with owlbear (yeah I know they get a lot of hate but they’re still a classic monster to me). Obviously small villages aren’t going to send someone to poke an owlbear awake just to see if it notices its shadow, but it might put a positive spin on late winter livestock attacks… if the owlbears are out early it’s a good sign for spring and an early harvest.

Random Encounters: Gamma World and Rifts

January 14, 2011 Note: For this blog entry I’m assuming the reader has familiarity with the Rifts setting, because, well, you wouldn’t really be interested in using it for your Gamma World Game if you didn’t.

Note: For this blog entry I’m assuming the reader has familiarity with the Rifts setting, because, well, you wouldn’t really be interested in using it for your Gamma World Game if you didn’t.

Last week I mentioned my desire to run a Gamma World game within the setting of Rifts. I’ve thought more about it and I definitely think it can be done with very little modification. I like the setting of the Gamma World game itself, its fun and I especially love the weird interpretations those on Gamma Terra have about the culture (and naming conventions) of the ‘ancients’ (us). But a ‘kitchen sink’ setting like Rifts offers a few advantages, the most important being the easy (and expected) importation of all the cool magical monsters from D&D. On the other side of things, I get to keep a setting I love while ditching a rule set I’ve come to loathe. I’m not the first to do this. Converting Rifts to other game systems is something of an internet wide pastime (which, in my opinion is a good barometer of how great a setting it is and how problematic the rules are). Of the blogs I follow there’s BTR (that’s better than rifts), Outsyder’s Spectrum Shock, the 4e Rifts Earth Saga, heck even Ryan Dancey (the father of open gaming) is on record saying that Rifts needed a d20 version (and that’s just the tip of the iceberg). There is such a demand that the forum at Palladium books even has a section detailing why they won’t allow Rifts to be converted to any other system (I’m just going to assume Palladium has enough problems of its own to care what I’m doing in the corner over here).

Characters

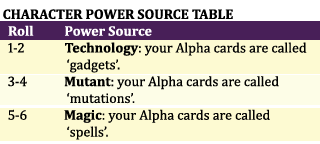

So how to make it work using Gamma World? The best attempt I’ve seen is here, and it takes the approach of creating new character origins based off of the Rifts O.C.C.s and R.C.C.s (juicers, power armor pilots, mind melters, etc.). The origins are good and it does a great job of directly translating the source material, but that’s not what I think is needed. In Gamma World, the more origins the better (that way there’s less of a chance of duplication within the party), so any approach that limits them to a static set I think is missing out on one of the appealing things about the game (plus it looks like each Gamma World supplement is going to add to the list). Instead, my solution is to have characters add another level of detail, layered on top of their origins, that filters their powers into something that would better fit in the world of Rifts. After all, the character creation process in Gamma World is all about interpreting how those origins interact with one another, the power source just guides that interpretation in a Rifts direction.

Using the table, characters can roll or choose a power source. Each power source gives a label to the character’s powers (Alpha mutation cards). So for example: an Electrokinetic Yeti with the technology power source could be a bionic Dog-boy with a built in neural mace attached to its arm; a Radioactive Gravity Controller with the magic power source could be a Ley-line Walker with ominous glowing eyes, always floating a few inches off the ground; and a Speedster Hypercognitive with the technology power source would be a perfect Juicer.

To continue the example: a bionic Dog-boy with the hostility Alpha card has learned how to short-circuit his neural mace to override a target’s cognition; a Ley-line Walker with the stoke resentment Alpha card casts the ‘wisps of confusion’ spell; and a Juicer with the venomous spurs Alpha card draws a poisoned switchblade (why are these powers always changing? That’s explained in the altered Rifts fluff at the end of the article).

Allowing for broad interpretations fits Gamma World better and I think allows for the kind of infinite possibilities necessary to recreate the tremendous variety of O.C.C.s and R.C.C.s in the Rifts game.

Other Rules

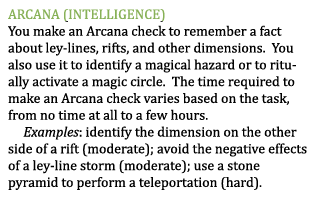

Add Arcana to the skill list (it screws up the symmetry of the skill list, but nothing’s perfect). When importing creatures from D&D add appropriate keywords: dragons, demons, elementals, undead, and goblins make great extradimensional monsters; grell, kruthik, mind flayers, and oozes make great extraterrestrial monsters; carrion crawlers, displacer beasts, owlbear, shambling mounds, and spiders make great terrestrial monsters. Finally add some magically oriented Omega Tech cards (these templates make it easy), like the TK -Machine gun, Cloak of Invisibility, Rune Weapons, and Symbiotes.

The World

A subtle change to the Rifts fluff brings the two games a little closer in line with one another:

“In the ages of the ancients, humanity lived in a golden age of prosperity. It was a time of high technology, human augmentation and fusion powered travel. Sages don’t agree on the causes of the ‘Big Mistake’ that awakened the rifts and brought down the apocalypse. Was it a global war of pride between the kingdoms of the ancients that snuffed out a billion souls whose backlash of psychic energy was too much for the earth’s ley lines to bear? Were the ancients being punished for ignoring the warning of their prophets that the stars would align for the return of the children of the Old Ones? Perhaps it was the hubris of ancient scientists at fabled ‘project arrowhead’ attempting to open a doorway to another world? Perhaps all are true.

Regardless of the cause, the results of the Big Mistake are plain for all to see. Ley lines, pathways of psychic energy that crisscrossed the planet, crackled with overflowing energy. Where these lines intersected the power was so great that rifts to other dimensions were torn through the fabric of space. Magic, once thought to be superstition and sleight of hand, became a powerful force in the world as real as science. Alien intelligences, demons, and creatures from nightmare poured through the rifts to invade our world. Atlantis rose from the ocean, unleashing biblical tsunamis on the world’s coastlines. Civilization ended almost overnight, but not before the ancients unleashed their most powerful weapons of mass destruction.

That was a hundred years ago. The Americas are a wasteland dotted with settlements carved out of the junk of the ancients. People use whatever they can to survive, be it scraps of technology, magical incantation or newfound mutant ability. But nothing is certain in this post apocalyptic age. The chaotic energy of the ley lines affects all things. Guns might stop working just as a machine that’s been dead for years lurches to life. Spells carved into millennia old tablets have random and unpredictable results. Mutants, their DNA forever altered by exposure to radiation and magic spontaneously grow wings and breathe fire.

It is a harsh world we have inherited from the ancients. One filled with monsters and uncertainty.” – from the History of the Wasteland, 101 P.A.