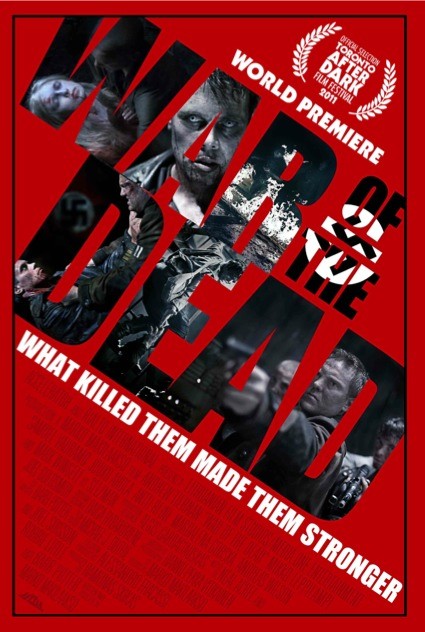

These It Came from the DVR articles are going to be a little bit different. As an early Christmas present to myself, I picked up a festival pass to the Toronto After Dark film festival. So the first difference is that these are new movies, on the big screen, instead of old ones and niche programming on the small screen. The second difference is that these are going to be short. I’ve got eighteen films to see in seven days (as well as dressing up for the annual zombie walk), so I’m not going to have a whole lot of time to write, and I want post these while the blood is still fresh.

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration, but most of the films it showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

Absentia

The story begins with Tricia, grappling over the decision to declare her husband ‘dead in absentia’, after he mysteriously vanished without a trace seven years ago. The legal declaration seems a first step to healing and moving on with her life but, instead of helping Tricia put her life together, she is tormented by the apparition of her missing husband.

Things are complicated by the arrival of Tricia’s younger sister, Callie, come to lend moral support but has problems of her own. It isn’t long before Callie finds an eerie pedestrian tunnel that she believes is connected not only with Tricia’s missing husband, but with a much older pattern of disappearances.

Creepy, Instant Indie-Horror Classic

I’m not one of those jaded horror fans that claims not to be frightened by movies. When they are good, scary movies scare me, which is why I go and see them (honestly I’m not sure why people who aren’t scared like horror movies – it’s a little like being an aficionado of tear-jerkers but never feeling sad). A good horror movie gets your blood racing in the theatre, but a great one stays with you as you leave and makes you walk a little faster on your way home from the subway station. Absentia had me hyper aware of all the weird little noises my house makes for a few days.

Part of what makes Absentia so effective is Mike Flanagan’s blending of the best parts of a ghost tale and a monster story. The ghost story elements give the film its melancholic atmosphere and sense of building dread, while the monster provides the clammy handed fear and jump scares only a creature skittering in the dark can.

Flanagan also knows how to really take advantage of the isolation one feels in the suburbs. Speaking as someone who grew up in the ‘burbs, I can attest to the strange quality they possess – at certain times of day, even if your rational mind tells you the rows of houses are filled with people, you feel like the last man on earth – a quality Absentia captures. Incidentally, my neighborhood also had a scary pedestrian tunnel (which I had to brave in order to get to my friend’s house), so the focus of the film had my inner childhood fears working overtime.

With a tiny budget (the movie was funded by kickstarter, which should be familiar to gamers as the funding source of choice for rpg start-ups), Absentia wisely leaves the heavy lifting to the excellent cast rather than special effects. I was especially impressed by the portrayal of sisters Tricia and Callie. Actresses Courtney Bell and Katie Parker did a great job filling their portrayal with the kind of knowing barbs (as well as loving support) only adult siblings can throw at each other. It had the added benefit of having their relationship to unfold for the viewer rather than artificially laying it out at the beginning of the film.

The concept of Absentia’s monster is very clever, and it unfolds in much the same way as the characters. Flanagan could have easily used a long expository scene (complete with a convenient scholarly expert opening up a giant tome full of woodcuts) in order to drive his ideas home, but thankfully resisted the temptation and took a much less forced approach.

Absentia is strongly recommended to all horror fans. The creep factor is in high gear and reminded me of the best parts of Insidious (the parts before the spirit world). Watch it with the lights off, and see how long you can sit in the dark alone when it’s finished.

SPOILER ALERT

I do have one criticism of Absentia, and I hate to bury it under a spoiler tag (like I did with Some Guy Who Kills People) since it has nothing to do with the plot, but I really don’t want to take any of the threat of the monster away from those who haven’t seen the film yet. Absentia left me needing to see more of the monster, enough that after the last scene I felt a tiny bit ripped off (just a bit – nothing like how ripped off I felt not seeing any aliens in Contact). I didn’t want to see the creature in broad daylight, I think that would have ruined it, and I understand why Flanagan didn’t include the traditional monster movie ‘reveal’. I’m not sure if it was entirely an editorial decision or a budgetary one. I just needed a little bit more. I realize a love of monsters is one of my idiosyncrasies, so it might not bug others like it did me. Ultimately, showing too much would have weakened the film so, even though Flanagan was stingy with the creature, he came down on the right side of that decision.

RPG Goodness

There is a definite trend in modern D&D products to move the fey away from their 1e roots as benevolent (or at worst neutral) forest spirits toward something much more dangerous and sinister. This trend can be seen in WOTC’s recent Heroes of the Feywild, but stretches back at least to the end of 3.5e with Paizo’s Carnival of Tears adventure. It’s a trend I happen to like, and one that might also be playing out on the stage of popular culture if Absentia is any indication (as well as Grimm and Lost Girl).

Without spoiling the clever ideas that I alluded to in my review of the film, Absentia is required viewing for any game master that wants to see how frightening the fey really can be. At first I thought the move to make fey dangerous was purely a pragmatic one – combat is a major component of the game, so it seems a waste to include game statistics for a bunch of flower sniffing pixies you aren’t going to get in a fight with. Other than harassing my players with some leprechauns (they appeal to the same side of me that thinks Snoti the snotling champion is awesome), I don’t think I’ve ever used a blink dog, brownie, or killmoulis in any edition of the game, so there might be something to that theory, but I don’t think it’s the whole story. While watching Absentia, I was reminded that the recent thematic transformation of the fey might actually be a revival of a much older view of faerie creatures.

Gary Gygax’s (and the rest of western culture’s) perception of the fey was probably informed by their Victorian interpretation (he did include Lord Dunsany in his list of inspirational reading, appendix N) as whimsical, fun-loving, child-like beings. However, there is an older interpretation of the fey, one that places many of the faerie creatures in the same mythological niche as vampires, ghosts, and demons. It is that tradition that I think Absentia and recent D&D products are tapping into.

Through this lens even the most benevolent fey of D&D’s past are transformed from innocent practical jokers to wild creatures filled with alien emotions and dangerous magic. As a DM you can play this up for full effect. Perhaps there is a sigil, or special herb the common folk put on their doors to ward against Eladrin, whom they view as unpredictable and dangerous – barely a step up from the murderous drow. A leprechaun’s legendary treasure is actually a pot filled with gold teeth, pilfered from corpses during the faery’s nightly grave robbing (a habit that puts them in close associating with ghouls). Brownies may help a desperate cobbler make shoes, but there is no telling what payment they may demand later on (anything from a silver plated laugh to the cobbler’s first born).

In such a world, making a pact with an arch-fey is just as dangerous as signing a contract with a devil or studying the maddening portents held in the movements of the stars and planets.

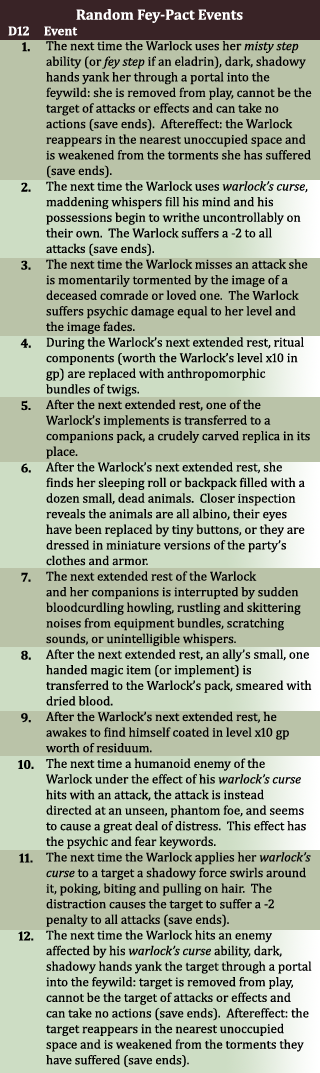

Random Fey-Pact Events

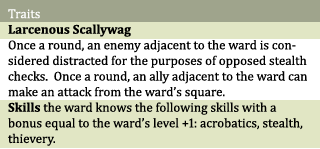

For those who have seen the feywild, its colours and smells are so vibrant and real it makes the mortal world seem like a sad reflection. It is no wonder the immortal beings that thrive in that atmosphere, the arch-fey, are so difficult to understand. Whatever their inscrutable motives for doing so, the arch-fey are known to lend some of their arcane secrets to mortals who interest them.

Unlike devils who frequently draw up well delineated contracts (if confusing and opaque) to entice mortal Warlocks, the unpredictable and mercurial arch-fey hold little stock in formal agreements (and frequently have a different understanding of them than mortals). More often than not, fey Warlocks aren’t even aware of the agreements they’ve entered into. The boundary between the worlds is thin in some places, and at these locations a mortal may accidentally leave a ritual offering or violate a sacred space, attracting the attention of an arch-fey. The fey Warlock walks a dangerous path. The relationship responsible for their newfound arcane powers is governed by alien whims and strange protocols. There is little the mortal mind can do to predict these fluctuating patterns. Instead the fey Warlock must learn to cope with the intrusion of the faerie world into their life, just as an infernal Warlock must learn to live with the eventual loss of their soul.

DM’s should roll on the following table every 2d6+2 days to determine the effects of the warlock’s arch-fey patron on the mortal world. Optionally, this table can also be used for Witches and other characters that have attracted the attention of an arch-fey, such as those with the Tuathan and Unseelie Agent themes (all from Heroes of the Feywild).