Archive for June 28, 2011

The Best Dragon Covers: 201-300

June 28, 2011As part of my ongoing celebration of Dragon Magazine’s 35th anniversary, I present the next instalment of covers, from issue 201 to 300.

These images represent quite a roller coaster ride through the ups and downs of Dungeons and Dragons. They bear witness to the development of the greatest settings the game has ever seen, the excesses and eventual decline of 2e, the demise of TSR, and the rebirth of the game in 3e under the ownership of Wizards of the Coast. Even though I had shifted to other games (namely Rifts) in the later days of 2e, I never strayed from Dragon (and even if I wasn’t in a campaign I always thought of D&D as my game). The writing, the ideas, and especially the art were always a great source of inspiration and entertainment.

I also liked the feeling of belonging to a community of gamers that came with the subscription. Yes that need has been fulfilled by the large (and vocal) gamer presence on the internet, but I don’t think anything will replace the visceral presence of a stack of physical artefacts (he says without irony while typing away on his blog – seriously, I can love my blog and the immediate and widespread distribution it has while still mythologizing the printed word, can’t I?).

One of the less positive aesthetic developments during this era was the inclusion of more text on the covers, obscuring the art. Fortunately, Dragon editors helped to mitigate this by publishing the cover art as a full page spread within the magazine. Since I’m focusing on the art of the magazine, I’ve chosen to reproduce those images and not the actual covers, even if it looks a bit strange not to see the familiar Dragon logo (as usual, click on the image for full size).

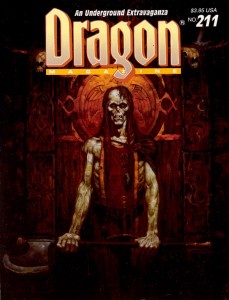

In the last article, I mentioned two of Brom’s fantastic Dark Sun images. He also painted a pair of covers for this run; two striking images of the undead. I always felt the first cover, for Dragon 211, was the perfect representation of a ju-ju zombie – an abomination created through life draining necromancy that retained some of its intelligence, could use weapons and had hard, leathery grey skin (and sadly hasn’t appeared in D&D since 2e). The halberd the creature wields also reminds me of old-school Citadel zombies (the ones armed with a cleaver-on-a-stick), which is a very good thing.

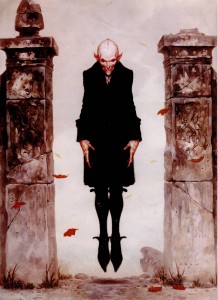

Brom’s second cover swings to the other side of the undead spectrum for Dragon 264, with a seriously creepy Nosferatu inspired vampire. Looking at the cover today, I continue to find Brom’s choice of vampire refreshing (in 1999 when this issue was published I was sick of Anne Rice copycats, today it’s the unmentionable ‘sparkly’ vampires of teen land). There is absolutely no question that Brom’s creation is a monster. With its rat-like teeth, beady eyes, and blotchy pinkish skin, the vampire is once again a living metaphor for the horrors of disease and the predatory nature of the aristocracy… not something to moon over and identify with.

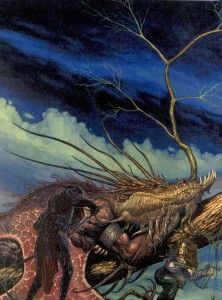

Another artist whose name should be familiar from the last article is Jeff Easley. Like the previous run, Easley was incredibly prolific in producing Dragon covers from 200-300, but these two are my favourite. Easley has painted a lot of dragons (I would say he is a master of the subject), but I think the cover to issue 225 stands out. Maybe it’s because I’ve got Caravaggio on the brain, but I love the dramatic impact of the dark, almost black tone. It really sucks you into the picture. Plus, I always appreciate it when an artist chooses to paint a dragon that doesn’t breathe fire. It’s a lot harder to visualize lightning breath, and as cool as King Ghidorah is, I’d rather have this as the go-to mental image whenever I think of blue dragons. Also, I’m not sure why undead and dragons go together, but apparently they do… and its unadulterated badassness.

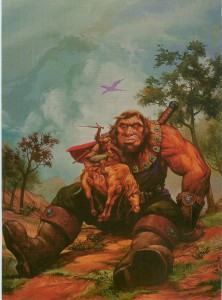

In tone, Easley’s cover for Dragon 254 is the polar opposite, and its naturalistic palette makes it seem almost like a landscape – which helps to suspend disbelief when you realize just how enormous that giant is. This cover echoes traditional fantasy renderings of giants which put into perspective just how small D&D giants are. I’ve never used a gargantua, or goriostro or similar sized monster in D&D, but I’ve always wanted to, and every time I look at this painting I feel like smacking myself for not designing that adventure yet.

There was a stretch during the middle of this run when every cover featured the magazine’s namesake. Now dragons are very cool (half of my favourite covers have them), but after a while it starts to get predictable (and if I recall, the letters column had some complaints about it). Fortunately, there are artists who can take any cliché and breathe new life into it. These covers still have the power to make me look at dragons in a different way.

R.K. Post is most well-known for his work setting the visual style for the Alternity game, but he also made several Dragon covers. The thing I love about his painting for issue 241 is how Post takes a well-travelled narrative (sneaking up on a sleeping dragon) and makes it as dark and full of twisted lines as his art. In this cover you cannot be sure of anything. The fighter in the foreground is cloaked in shadow, drawing a cruel looking blade. Is he the hero of this tale, or the villain? Instead of reclining on a bed of stolen riches, this dragon lays on a mighty tree, with which it blends seamlessly, like a creature of nature. It’s also nice to see a bard as part of the action, something you don’t often witness in D&D illustration.

If I could use a single word to describe Tony DiTerlizzi’s cover for Dragon 242 it would be ‘charming’. DiTerlizzi helped bring the Planescape setting to life with his incredible ink and watercolour pictures. Most of those were dark and sketchy, as suited the down and dirty flavour of Sigil, but here DiTerlizzi shows us he can also work with a lighter palette and more refined lines. It’s also full of whimsical little details that ensure I’ll never get bored of looking at it – the dice on top of the D&D books, the strange orrery, and especially the dragon’s tiny spectacles. This painting helps to remind me that dragons aren’t just dumb brutes there to blindly rip apart adventurers. They are some of the most intelligent creatures in the game, have their own goals, and just maybe, indulge in the occasional game of chess.

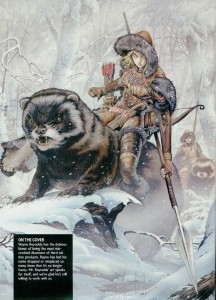

The next pair of covers each feature paintings with interesting mounts and riders. I’ve never had the chance to play a character with a special mount (I’m usually the DM for our gaming group), but these pictures hold enough inspiration that I feel left out.

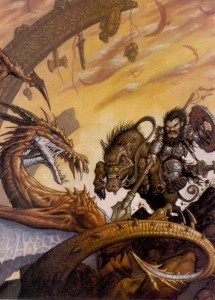

Matt Wilson is now the co-owner of Privateer Press, but in the nineties he did a bit of work for TSR, including this cover for Dragon 245. Dwarves aren’t one of those fantasy races you usually associate with cavalry, but once you see a dwarf knight on a razor tusked boar pulling a St. George, you know it’s right. Looking at this painting today, I also find it interesting to see the proto-vision of the style that would one day be associated with the Warmachine game.

I mentioned veteran Dragon artist Fred Fields last article, and you can see how much his style changed over the years from Frazetta-like heroic fantasy to a gritty photo-realistic one. When Dragon 248 came out (1998), I was playing a lot of Rifts, so I had a natural inclination to like the genre crossing for its cover (the goggles, for flying without a canopy are a nice touch). Of course in Rifts you can be a dragon, so my friends and I would joke that the guy with the machine gun was actually the dragon’s familiar.

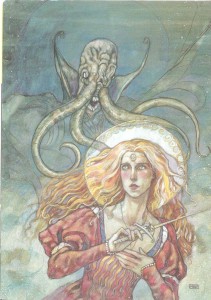

I know a lot of people hate them, but I have always loved psionics in D&D (yes, even in 2e when they were obviously broken, but who didn’t love rolling for wild talents?). One of my favourite issues of Dragon covering the subject was 255, with a stunning watercolour cover by Rebecca Guay (I liked the issue so much it’s the only time I ever wrote to the magazine – and I had my letter published in 259!). I love the almost medieval look of her lines, and the light washes of paint make the image look ethereal – perfect qualities to depict a psionic struggle between heroine and mind flayer. This battle could easily be taking place in the physical world, the mental plane, or a blending of our perceptions of the two.

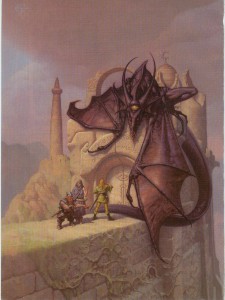

I was ignorant or Mark Zug’s work until I looked up the artist of these two long-time favourite Dragon covers. Besides depicting an awesome bat-creature acting as a guardian of a magically sealed doorway, Zug’s cover for Dragon 271 also contains a hidden message spelled out in those runes. I’ve never figured out what it says, but I like knowing that there’s a mystery to be solved. It’s this kind of Easter egg that moves a painting from being a fantasy illustration to a specifically D&D one.

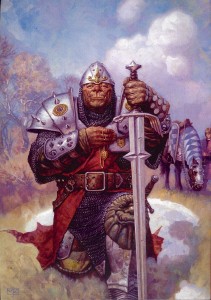

Nothing signifies the transition to 3e more than this cover for Dragon 275. Yes, the magazine had switched over to the new edition in the previous issue, but Zug’s painting of a noble half-orc paladin summed up the shift in the game’s philosophy without words – no more boundaries.

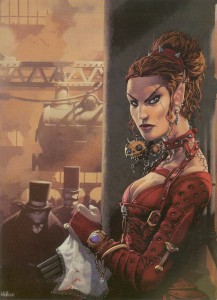

There is so much to dig about Kev Walker’s cover for Dragon 277, the multi-barrelled pistol concealed under a lace handkerchief, a badass elf in studded leather, locomotives, Victorian fog, and you have to love that half-orc with the righteous mutton chops in the background. If you have ever wanted to play a steampunk version of D&D, this painting is it.

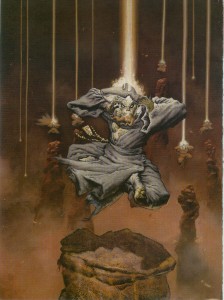

I mentioned my love for psionics, so it’s no surprise that I included Paolo Parente’s cover for Dragon 281 in this list. It’s doubly hard to make a visual representation of mental power, both because psionics by their nature, have far few optical effects than traditional magic, and also because there isn’t a deep well of reference material for artists to plumb. Parente takes these limitations and grinds them into the ground. This picture of a group of Githzerai in meditation (as well as Rebecca Guay’s), present the best argument for the place of psionics in a fantasy setting.

The rise of 3e is also the rise of artist Wayne Reynolds. Like Brom with Dark Sun, WAR (as he signs his pieces) was responsible for the visual style of Eberron (and with all the covers and large color illustrations he did for other 3e products, it could be argued he helped define the style of the edition itself). No run of Dragon covers that includes 3e material could be complete without a WAR painting. His work always has a dynamic sense of action that really energizes me and makes me want to start rolling dice now. I also like this piece for the things it doesn’t include: ‘boob windows’ (to use Wundergeek’s term) and adventure inappropriate clothing – art crimes WAR has definitely been guilty of in his body of work.

In the next instalment I’ll look at the bittersweet final years of Dragon.

Shadows in the Moonlight- Part One

June 21, 2011There is a lot for DMs to learn in Shadows in the Moonlight. In D&D terms, the island where the action of the story takes place is definitely a location based adventure, but it is also an amazing example of what game designers call a ‘living dungeon’ – one where the actions of the PCs influence the actions of the NPCs and both react to the island’s set encounters.

This story has the added bonus of a female character who subtly subverts the whole damsel in distress motif that was bothering me a few stories ago. Yes, Olivia is a damsel in distress, but she’s also capable of driving the plot forward on her own, and is more than just a prize to be won by the Cimmerian at the end of the story. In fact, although told in the third person, the story is obviously from Olivia’s point of view, making her the reader’s ‘eyes’.

Spoiler Alert! All of these Hyborian age posts are going to be filled with spoilers. From the summary, to the monster stats they are going to ruin any surprises as to what the monster is, when they pop up in the story and how and why they are killed. You’ve been warned.

Summary

Howard’s tale begins with Olivia, daughter of the King of Ophir, sold into slavery because she would not marry a King of Koth, fleeing her former master, the Hyrkanian Shah Amurath. On the swampy boundary of the Vilayet Sea, Shah Amurath reaches his quarry. As fate would have it, the salt marsh is also the temporary refuge of Conan, himself fleeing from Shah Amurath’s troops who had recently slaughtered the Cimmerian’s rogue mercenary army, the Free Companions. Mad with starvation and a burning desire for revenge, Conan throws himself at Amurath. The Hyrkanian’s superior weapons and armour pale before the furious onslaught of the barbarian, and in a few bloody moments of mad butchery he is cut down. His bloodlust sated, Conan returns to his senses and introduces himself to Olivia. Soon after, the pair decides to escape in a stolen rowboat before they are caught red handed by the deceased Shah’s men.

After a day of hard rowing, Conan lands the craft on a small deserted island to rest and gather some food. It isn’t long before they are ambushed by a huge hunk of hurled stone. Conan investigates, and after a few moments draws his weapon, grabs his companion and slowly backs out of the trees. Whatever it is that had unnerved the barbarian, Olivia cannot see it.

Moving through the island’s grassy hills, the two stumble upon the ruins of an ancient building. Eager to get as far from the jungle as possible, Conan and Olivia enter. Inside they find the hall of the long, low building is filled with incredibly lifelike iron statues of unsettling humanoids. The sculptures are disturbing, but poking and prodding reveal them to be as solid as they appear. Safe from their mysterious jungle stalker, Conan and Olivia drift off to sleep.

Instead of blissful rest, Olivia is plagued with an incredibly realistic nightmare. She sees the building as it once was, filled with the humanoids depicted in the statues. They torment a beautiful angelic figure chained to a pillar. To no avail, the angel creature wails to the heavens. A moment later, the dark humanoids open its throat in bloody sacrifice. Suddenly, the skies open wide and a being that could only be described as an exquisite and terrible god steps down among the savages. Cradling the body of its slain progeny, the god pronounces a powerful curse in its alien tongue. The humanoids freeze, transfixed, their bodies metamorphosed into solid iron. The deity then points to the moon, hanging in the night sky, and departs.

Olivia wakes screaming, and despite Conan’s protests that the statues are harmless, manages to convince the barbarian to leave at once. As frightened as she is about the iron figures coming back to life, Conan is more concerned about whatever lurks in the concealing jungle, so the pair take refuge on the island’s rocky cliffs.

The next day, from their high vantage point, Conan spies a pirate ship pulling ashore, spilling its ragtag occupants in search of supplies. The barbarian knows the ship is the best opportunity to safely leave the island and be rid of the Hyrkanians, so he hatches a scheme. In case his plan doesn’t work, Olivia hides while Conan confronts the pirates of the red brotherhood.

Unfortunately, the leader of the pirates is already well acquainted with Conan, and has a score to settle. Outnumbered, Conan goads the pirate captain into single combat, and handily slays him. Before he can parlay the victory into something more, an overzealous pirate brains Conan with a sling stone. Without the iron hand of a leader to guide them, the red brotherhood argues amongst themselves over the fate of the unconscious and bleeding Cimmerian.

Unaware of Olivia, the pirates bind Conan and drag him back to the ruins, where they set up camp for the night. Fearing the coming evil of the moonrise, Olivia braves both the jagged cliff face and pursuit by the shadowy stalker that has hounded them since their arrival. Inside the ruins, she creeps past the sleeping and drunken pirates to free Conan and escape.

They do not make it far when they finally meet Olivia’s pursuer face to face. Their mysterious assailant emerges from the shadows; a bestial man-eating grey ape. It was time for a reckoning in the only manner that Conan knew how. Barbarian and beast clash, but with the advantage of steel, Conan leaves the ape a broken and dismembered corpse.

The jungle brute was dead, but the island had yet to play its final hand. From the ruins came a series of bloodcurdling screams, the clash of steel, and the sound of unbridled butchery. Olivia’s dream had come to pass – the moonlight had just reached the crumbling building. Not eager to see the nightmare first hand, Olivia and Conan take flight to the pirate’s abandoned ship.

The morning light brings a small group of wounded and shaken pirates who managed to escape the massacre with their lives. Conan allows them to board what was once their ship – provided they acknowledge him as their captain. With a ship and a crew to replace the Free Companions, Conan was ready once again to plunder his way to vengeance across the inland sea.

Iron Shadow

“They were statues, apparently of iron, black and shining as if continually polished. They were life-sized, depicting tall, lithely powerful men, with cruel hawk-like faces. They were naked, and every swell, depression and contour of joint and sinew was represented with incredible realism. But the most life-like feature was their proud, intolerant faces.” – Robert E. Howard, Shadows in the Moonlight.

When the gods are angered the world trembles. When there is a blasphemy so obscene it demands justice, such as the ritual murder of a deity’s demigod offspring, the gods do not act through proxies, and iron shadows are left in their wake.

Iron shadows are the product of an ancient divine curse, transformed into metal statues to guard over the site of their cosmic crime until the end of time. As such, they are usually found in the crumbling remains of prehistoric dungeons, the ruins of primordial temples, and on blasted mountain peaks shunned by all sentient races. They are immobile, forced to watch without being able to act, until an environmental condition, laid out at the time of their cursing is satisfied. Such a condition could be anything from the light of the moon to a breath of air in a subterranean chamber, but once it has been met, the iron shadows are temporarily transformed back into flesh and blood creatures; free to release centuries of bottled hatred on any unfortunate enough to cross their path.

Only the gods themselves know why they would allow the objects of their curse even the briefest freedom from punishment. Perhaps the terror iron shadows invoke serves as a reminder to the world the consequences for the ultimate blasphemy.

Only the most depraved of the thinking races have incurred this divine curse, including black ones, derro, drow, gnolls, goblins, humans, kuo-toa, and troglodytes. Some iron shadows are so old that they have outlived their decadent civilizations, and even the names of their species are lost to the sands of time.

The iron shadow theme adds an element of lurker to any monster, and works best on a group of creatures in a set-piece encounter that reinforces the blasphemous act that offended the divine. Alternatively, iron shadow themed monsters work well in an area the characters must travel through frequently, and have been lulled into a false sense of security by the statues’ prior inactivity.

Skill Modifications: +2 bonus to Stealth, and a +2 bonus to one of the following knowledge skills – Arcana, Dungeoneering, History or Religion.

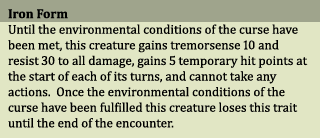

Traits

All iron shadows gain the following trait, which simulates their cursed sta te:

te:

Attack Powers

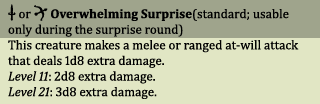

The nature of their curse means that Iron Shadows most often attack from surprise, surrounding their foes and bringing down the weakest targets as quickly as possible. Although the survivors of such an onslaught often flee, the divine magic of the iron shadows’ curse binds them to the area and prevents pursuit.

Fearsome Aspect

This power emphasises the sudden and frightening nature of an iron shadow attack. It works best in an encounter area that directly blocks the characters’ objective, since all or some of the party may be forced to flee.

This power makes the opening attack of a lurker even more devastating, or adds an element of lurker to any other monster role.

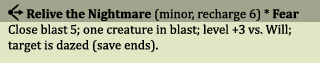

Relive the Nightmare

When added to a lurker (or other creature with bonuses against targets that grant combat advantage), this power helps to increase damage potential. Relive the nightmare also gives the dungeon master the opportunity to describe the events surrounding the iron shadow’s curse, and inject pieces of narrative into the combat.

Utility Powers

Iron shadow utility powers focus on keeping lurkers and artillery alive long enough to cause the maximum amount of damage.

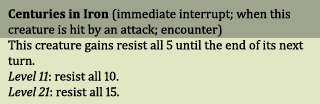

Centuries in Iron

Over time, some iron shadows have learned to harness the deific curse to their own advantage. This protective power is especially useful for lurkers and artillery that are prone to succumbing to the effects of focused damage.

Palpable Hatred

This power helps to protect artillery from melee combatants, keep skirmishers mobile and prevent lurkers from being surrounded by foes.

Notes

Wow, I’ve never made a theme before and I have to admit it was a lot more work than I thought it would be (much more than creating a single monster, which in hindsight makes sense). Of course, the fact that the battle with the monsters isn’t directly described in the story didn’t help either. Still, I think making a theme to represent the isle of iron statues was definitely the right choice. This way, almost any creature can be turned in to what amounts to an iron gargoyle – which I think has a lot more utility than a single similar monster.

I’m pretty sure that the statue creatures in the story are the black ones from the Pool of the Black One (their physical description is comparable as well as the strange green stone of their buildings). I find the presence of these creatures in both stories very interesting for what it means about the setting of the Hyborian age. In his essays, as well as the Conan and Kull stories, Howard writes at length about the ancient civilizations of the serpent people, Stygia and Acheron, but he makes no mention of the black ones. Being present as far west as the Atlantic, and as far east as the Vilayet, suggests remnant pockets of what at one time must have been a much more widespread race (plus the green stone of the city of Xuthal in the south suggests that they may have been the original builders), probably incredibly old even in Kull’s time, before Atlantis sunk beneath the waves. A quick internet search reveals I’m not the first person to question the relation between these stories, but it’s still an interesting point to ponder nonetheless.

The Best Dragon Covers: 101-200

June 15, 2011This month Dragon magazine reaches two milestones: its 400th issue and its 35th anniversary. To celebrate, they’re looking back on the magazine’s storied history and the WOTC website has created an online gallery featuring the cover art of Dragon’s first 100 issues. The covers of Dragon are a great source of gaming inspiration, and feature some of the best talent in fantasy illustration. The art was so good that TSR often reused it in its other products (which drew its share of criticism but never bothered me – it made me feel like an ‘insider’ when I recognized a painting from Dragon). For me the covers also signify something in addition to great art. My interest in Dragon magazine grew as I made the transition from player to dungeon master, developing into a very long subscription and culminating in what some would call an obsession (well, anyone who’s seen the boxes of magazines on my book shelves).

There are some excellent covers in those first 100 issues (seriously, check them out now), including Denis Beauvais’ incredible series of chess themed paintings (probably my all-time favourites), but I missed out on most of them. The very first issue of Dragon that I owned was number 87, indefinitely borrowed from my school library (don’t tell Baythorn Public School). Sure, later I acquired many pre-100 issues, but it wasn’t quite the same. I read the back issues with the eyes of a collector. When my monthly copy of Dragon came in the mail though, I absolutely devoured every page. And when I wasn’t reading, those covers stared up at me from my pile of gaming books spread across my mom’s kitchen table.

So I’m joining the celebration and over the next couple of weeks I’ll showcase some of the magazine’s stand-out covers – post issue 100. These are images that for one reason or another have stuck with me over the years, and flipping through my collection today they still have an emotional impact. It was nice to have the excuse to get reacquainted with some old friends (as usual, click on the pictures to see them full size).

Issue 116 featured an amazing scratch-built model of a red dragon by Peter Botsis. I really love the combination of miniature painting and smoke effects – the three-dimensionality somehow makes it seem more real to me than a traditional painting. It took me a decade and a half of waiting, but in University I was finally able to combine dry ice and miniatures for my own tabletop game (thanks to a friend who works at a lab) – although instead of dragon smoke it simulated the fetid miasma of the Hive for a Planescape campaign.

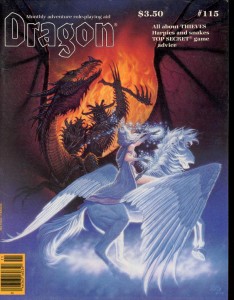

The cover of issue 115, the Antagonists by Denis Beauvais (of the chess covers) is truly a classic. Many of his covers featured the struggle between good and evil, but what I love about this painting is how the composition engages the viewer by putting them on the side of light, confronting the demonic forces of darkness face to face (almost daring you to open the cover and face the dangers within). I’m pretty sure that’s the first time I ever saw bladed wolverine style armguards as well, a look that surely influenced artists like Brom and Wayne Reynolds. Oh, and it was so badass that Ral Partha immortalized it in miniature form.

A frost giant skeleton bursting out of a snow bank hardly seems subtle, but my favourite parts of the cover of issue 126 by Daniel Horne are the small details that move your eye around the page and tell a story without words. The skeleton’s missing finger, the sword lodged in its armour, the ineffectual scattering of arrows, the empty quiver, and finally, if you look very closely, you can see that the last arrow gives off a slight glow… an arrow of undead slaying perhaps? It’s also nice to see a female character dressed appropriately for adventuring.

Dragon 127 and 129 are both Keith Parkinson paintings and both were reused in more than one TSR product (the Big Stash – the one with the dwarves, I remember being included in a Forgotten Realms calendar I got for my birthday when I was a kid). Parkinson was a master of atmosphere and the paintings’ multiple appearances are a testament to that. With his painterly style and slice of life (fantasy life that is) subject matter you can’t help but be drawn into the D&D game world with these covers.

I’ve mentioned before how much I like Jeff Easley’s dragons, but the cover of Dragon 138 shows that he can do just as well depicting the undead. I really dig the earthy palette of this painting – it reminds me of a freshly churned grave (in true horror movie style with a rotting up-thrust hand of course). Dragon’s October issues had a long tradition of following a Halloween theme, and I always looked forward to them.

Fred Fields did a lot of work for TSR, but this cover for Dragon 142 stands out for two reasons. The first is purely nostalgic. This issue of Dragon marks the transition from 1e to 2e D&D. I was buying every issue in the local games store by then and it was soon after this that I got my subscription. The other reason I love this picture is that it represents a scene that every dungeon master has wanted to spring on his players, the classic ‘that hill you are sitting on is actually a dragon’ (which just beats out ‘that cave you walked into is actually a monster’s mouth’). I never managed to pull that one off, even though I set an adventure with a black dragon in a swamp shortly after this came out.

I enjoy the cover of Dragon 148 by Ned Dameron for similar sentimental reasons. This issue was awesome because it had a cardstock insert of the infamous magic item, the deck of many things. I immediately inserted it into the campaign I was running (totally disrupting it with excessive amounts of magic) and that meant keeping this issue on hand. There’s something to be said of the hard bitten everyman adventurer of old school art, but to a scrawny kid getting ready to enter high school for the first time, these were the kind of larger than life demigods that I wanted to play (I rooted for the guy with the Morningstar, since I thought he was a thief, and they were my favourite class).

It might be the sense of dread evoked by the sickly green glow reflecting off of the bugbears’ scales (actually I’m not exactly sure what they are, but I always assumed they were bugbears because of their ears and sneaky disposition), but it’s probably just the expression on the little bastard’s face in the bottom right corner that makes me love this cover for Dragon 152 by Paul Jaquays. When I was a kid, I played with a guy whose character was always running off and trying to steal all the treasure. I wanted him to get his just desserts, like the subject of this painting.

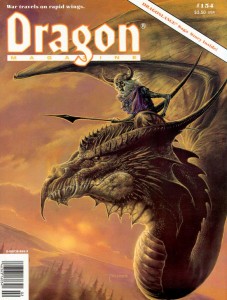

There’s not more of a reason why I like the cover of Dragon 154 by Bob Eggleton other than I think it looks like an awesome monster combination. Earthtones and undead definitely feel right together… A theme picked up by Michael Weaver for Dragon 162 (surprise, another Halloween issue). The more I stare at this painting the more I feel haunted. The hollow, rusted armour, the emotionless disembodied head, the lonely fall colouration – for some reason it all reminds me of the ravine near my mother’s house (not that its filled with the restless dead, it’s just that certain parts of the ravine had a definite character that I see in this cover).

Gerald Brom’s unique paintings captured the brutal savagery of Frank Frazetta and infused them with a dark edge that twisted everything into an alien form – a style that was absolutely perfect for the Dark Sun setting. In fact, Brom’s style is so synonymous with Dark Sun that Wayne Reynolds paid obvious tribute to his work with the covers of the 4e revamp of the game world. Brom made two Dark Sun themed covers for Dragon, issues 173 and 185. The first issue, with the belgoi, had me sold on Athas, and I bought the boxed set soon after. Brom’s work was also immortalized by Ral Partha, although they used the belgoi as a model for their gith shaman.

Larry Elmore is one of the giants of fantasy illustration, and he painted a lot of covers for Dragon magazine, but looking back through my collection I have to admit that most of them didn’t really jump out at me as exceptional (unlike his product and book covers for which his reputation is well deserved). Most of Elmore’s covers were just pretty women standing idly in front of a scenic backdrop. They were well executed technically, but they didn’t inflame my imagination. Unlike those paintings, the cover of Dragon 200 lives up to Elmore’s exceptional Dragonlance work… plus it had a hologram (in the eighties if you wanted to jazz something up you made it glow-in-the-dark, in the nineties it was holograms).

In the next instalment I’ll look at Dragon’s covers post 200.

Random Encounters: Ilya Ivanov, real life Dr. Moreau

June 10, 2011I’ve always thought the RPG Blog Carnival was a cool idea – a group of writers coming together just for the fun of exploring an interesting theme (like a digital flash mob); but the topics covered so far have been outside of the focus of this site. Fortunately, this month’s host for the carnival, Dungeon’s Master, have set a theme I can really sink my teeth into: RPG characters based on real life people (using no less awesome an example than Seth Grahame-Smith’s Abraham Lincoln, Vampire Slayer).

Growing up, my father, an electrical engineer, taught me a healthy respect for alternating current, so naturally my first choice was Nikola Tesla, but Greg at Lungfishopolis beat me to the punch. So I decided to move on to another, lesser known eastern European ‘mad scientist ’, Ilya Ivanov.

’, Ilya Ivanov.

Ilya Ivanov was a Russian biologist who worked from the turn of the century until the early 1930’s. He pioneered revolutionary artificial insemination techniques and used the technology to create a wide variety of hybrids, including zebra-donkey, antelope-cow, and rabbit-guinea pig mixes (hello owlbear!). As if that wasn’t enough RPG fodder, Ivanov is most infamous for his efforts to create a human-ape hybrid. His first attempts using apes impregnated with human sperm failed. Logically then, the next step was to impregnate human females with ape sperm. In spite of actually having a volunteer willing to carry the hybrid, Ilya Ivanov was arrested in one of Stalin’s shakedowns of the Russian scientific community before he could get the experiment underway. As far as I know, Stalin had no moral objection to human-ape crossbreeds, and the arrest was a purely political one. Ivanov never got a chance to return to his mad work, dying in exile in Kazakhstan in 1932.

Not surprisingly, since then Ivanov pops up regularly in conspiracy theories, fringe science, and pop culture every few years (or the shadow of his ideas do). The forbidden and frightening act of creating a human hybrid, mixed with the sinister exoticism of Stalinist Russia is a brew too powerful to resist. Seriously, we’re talking about an army of cold war, soviet, super apes! That’s pure gold.

The legacy of Ilya Ivanov can be felt in the classic Fantastic Four villain Red Ghost (and his super apes), in DC’s Gorilla Grodd, and in the Planet of the Apes movies (including the soon to be released reboot, Rise of the Planet of the Apes).

Taking my cue from Seth Grahame-Smith, I’m going to use a similar over the top approach; one that posits Ivanov succeeding where h istory tells us he failed. And I can think of no better RPG suited to house Ilya Ivanov than one already filled with mutant animals, a blatant disregard for the laws of nature and bucket loads of cold war sensibility: Gamma World.

istory tells us he failed. And I can think of no better RPG suited to house Ilya Ivanov than one already filled with mutant animals, a blatant disregard for the laws of nature and bucket loads of cold war sensibility: Gamma World.

I present, for use with the current edition of Gamma World (as well as Dungeons and Dragons), Ilya Ivanov and his super apes.

United Soviet Simian Republic

“Species of the world, unite! (Literally)”

Ilya Ivanov was a soviet scientist who worked to create the first human-ape hybrid. In most realities he failed and was arrested by Stalin, but in a few, the mad visionary was able to escape imprisonment and create an army of super apes. With his hybrid commandoes, Ivanov quickly overthrew Stalin and carved out a new Soviet empire. Ivanov, in his role as dictator, ushered in an age of undreamed scientific progress untainted by political ideology, and unfettered by morality or ethics.

By the time of the Big Mistake, Ivanov had ‘outgrown’ his old, perishing body and had transferred his brain to a series of simian hosts.

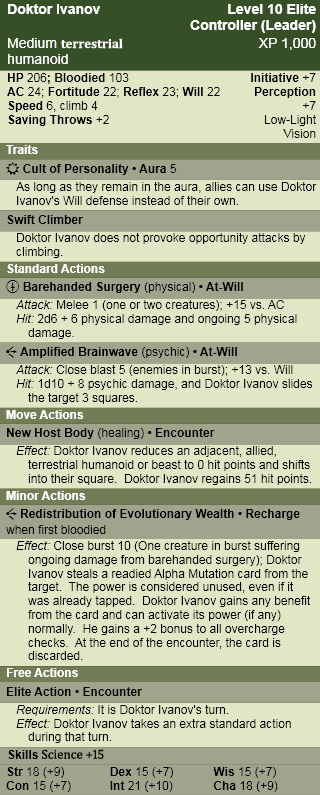

Doktor Ivanov

“You know how I know that monkey is smart? I can see its brain.”

Doktor Ivanov lost the last shreds of his empathy when he abandoned his human body and put his brain in a jar. Now he views everything through the cold, detached lens of a science experiment. In combat Ivanov uses his bestial strength to rip raw hunks of meat out of his opponents, analyze their genetic imprints, and absorb any beneficial mutations found for further study. Should his host body become damaged in his pursuit of test subjects, Doktor Ivanov doesn’t hesitate to transfer his brain to one of his humanzee ‘children’. That the process decapitates the host doesn’t seem to bother either Ivanov or his creations.

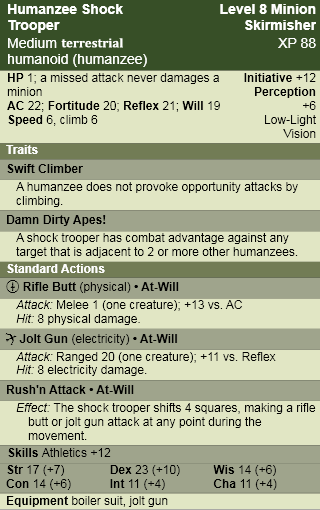

Humanzee Shock Trooper

“To err is human, to ape divine.”

Humanzees combine humanity’s capacity for war and violence with the strength and agility of an ape. They are the perfect soldiers, and ob ey strong commanders without question so long as there is war to wage. Even on Gamma Terra, there is little more horrifying than seeing the raw hatred and naked brutality of a swarm of boiler suited humanzees washing over their foes like a crimson tidal wave.

ey strong commanders without question so long as there is war to wage. Even on Gamma Terra, there is little more horrifying than seeing the raw hatred and naked brutality of a swarm of boiler suited humanzees washing over their foes like a crimson tidal wave.

LoreAlthough he built his empire with the savage power of human-ape hybrids (and they remain his most successful creation), Doktor Ivanov experimented with many other human –animal combinations. With the proliferation of creatures such as badders, hoops, dabbers, fen, and porkers wandering the wastes one has to wonder if prevailing origin theories are wrong and these beasts are actually the orphaned offspring of Ivanov’s abandoned experiments.

Notes

I did it. I made another ape monster even though I promised I would keep them to a minimum. I really did want to stat-up Tesla, and when I was looking around for other real life mad scientists to replace him Ivanov just jumped out at me. I’m glad I broke my promise though, I really like how everything came together (there were a few Gamma World monsters that affected the use of Alpha and Omega cards but nothing that took advantage of the card mechanic itself, so I wanted to incorporate that into the design). Plus, I really wasn’t happy with how the picture for Thak turned out, and I wanted another shot at drawing a primate before the next instalment of Monsters of the Hyborian Age.

Incidentally, the brain in a jar aspect of the monster was inspired by another Russian, a contemporary named Sergei Bryukhonenko, who invented a heart and lung machine that could keep a dog’s head alive and responsive detached from its body. I’m sure Ivanov would have had access to that technology during his soviet renaissance of scientific research.