Posts Tagged ‘Blather’

The Best Dungeon Covers: 76-fin

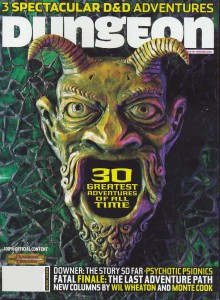

June 8, 2012This is the second (and final) installment of my celebration of Dungeon magazine’s 200th issue (click here for the best cover art of the first 75 issues). The latter half of Dungeon’s print run was an interesting time for the magazine. It saw the rise of 3e and the founding of Paizo. Even more importantly though, it was in the pages of Dungeon that the ‘adventure path’ format was born – a series of adventures linked together by an overarching plot (taking characters from 1st level to 20th) – a campaign in serial form. Dungeon’s adventure paths set a new standard in the industry and the format proved so successful that Paizo was able to base their entire business around publishing them when WOTC cancelled the print versions of Dragon and Dungeon …and spin that achievement into their own version of D&D at least as successful as 4e (I wouldn’t hesitate to say that the Pathfinder rpg owes its existence to the development of the adventure path).

If Dungeon is 200 why stop at issue 150? As I mentioned in my retrospective on Dragon magazine covers, cover art lost its place of cultural primacy when the magazines underwent their digital rebirth (you can see a similar phenomenon with album art in the age of iTunes). Digital covers don’t serve the same function (a combination of product packaging and advertisement), and as a result have little influence on the gaming world – the equivalent of a vestigial organ. That might sound harsh, but it’s not an indictment of WOTC’s digital initiative (I think the accessibility, low cost, and portability of PDFs are great), just a lamentation for a lost art form. Let’s take a look at some of Dungeon’s best examples and remember a time when cover art was king (click on images for full size).

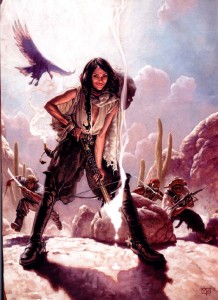

I fell in love with the cover to issue 80, by Mark Zug, the moment I laid eyes on it. The mash-up of D&D and the wild west is fantastic, irreverent and avoids descending into campiness. The two visual themes blend together so well that neither the hats nor the crossbows seem out of place (the magical bolt standing in for a smoking shotgun). But that’s not what draws the viewer’s eye immediately to the center of this piece – it’s the wicked smile of the character in the foreground (Tonja, the leader of a group of desert bandits in the adventure Fortune Favors the Dead). Imbuing a figure with real personality, as Zug has done, is extraordinarily difficult (that’s why portraiture is so demanding). That smile is so compelling I wonder how many people have overlooked that the bandit leader is supposed to be an NPC and used this cover as a character portrait.

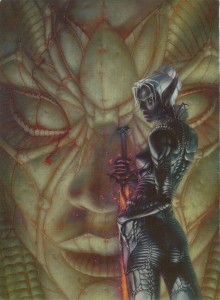

Another femme fatale, Laveth the daughter of Lolth, courtesy of Stephen Daniele for the cover of Dungeon 84. There’s a bit of cheesecake going on in this painting (especially that ‘America’s Next Top Model’ pose) but the artist’s ability to capture the essence of the drow so well elevates it above mere fan-service. Daniele is definitely channeling H.R. Giger’s biomechanical work here (always a good thing in my opinion), and it fits perfectly. Laveth’s armor looks like the chitinous shell of a spider, a great visual cue that not only ties the drow to the goddess of arachnids, but also reminds the viewer that everything about the dark elves is twisted, alien, and dangerous. The pale statue in the background, with clusters of spiders that look like bloody tears, is a nice touch as well.

The cover for Dungeon 90 is, aside from his Dark Sun work, one of Brom’s best paintings (and there are a lot to choose from – Brom’s works have made it onto all but one of my lists of the best Dragon and Dungeon covers). It features a priestess of Loviatar and her undead ally. The devourer, rendered in pale ghostly tones is very much in (what I call) Brom’s ‘gothic mode’. The evil spirit is truly frightening, and the pathetic soul of a vanquished paladin trapped within its ribcage makes this cover a strong argument for why the devourer, added to the game during 3e, is an instant classic. What makes this painting one of my favorites among Brom’s work though, is the figure of the priestess. I love her blood red monochromatic color scheme, and the artist’s choice to give her a more exotic, non-European look is something you don’t see often in the art of D&D and it’s a refreshing departure.

It would have been easy to fill this list with nothing but Wayne Reynolds’ paintings – he created a tremendous number of Dungeon covers during the 3e period most of them were exceptional. While he still dominates this list, I opted instead for his best four (plus a bonus cover at the end). Even if you aren’t a Reynolds fan, you have to be impressed with the sheer volume of the work he put out during these years (and he still produces an impressive output for Paizo).

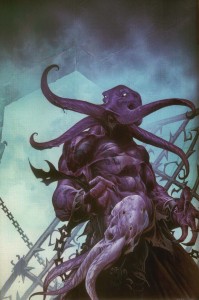

Reynolds’ cover for issue 94 features one of my favorite monsters, the craziest mind flayer villain of all time, Absterthelid, a creature with a taste for the brains of his own kind (a great idea made insane by a stat block that combined mind flayer and monk to take advantage of the mechanics of the extract brain special ability – truly a monster). Reynolds takes the classically cerebral image of the mind flayer and transforms it into a beast of physicality. The cast-off, brainless husk of a traditional mind flayer completes the image, giving the viewer everything they need to know about both Absterthelid and Reynolds’ larger than life approach to illustration.

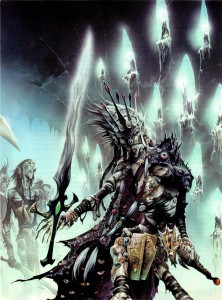

Dungeon celebrated its 100th issue with ‘incursion’, an event spread between Dungeon and Dragon that saw the githyanki invading the prime material plane. It’s a very cool concept (one that I planned to incorporate into a long running Planescape campaign, but never got the chance to), and Wayne Reynolds’ painting of Vlaakith, the lich-queen of the githyanki is even cooler. Though her physical form is withered and mummified, Reynolds leaves no question as to Vlaakith’s arcane might. I especially like Reynolds’ disturbing take on the robe of eyes, a fitting accoutrement for a queen who sustains herself with the life force of her subjects. Reynolds sometimes gets flak for the awkward positioning of his female subjects, but in this case it works. Vlaakith’s pose reminds me of the contorted rigor mortis of Boris Karloff in The Mummy (and I’m happy Reynolds resisted the urge to make a ‘sexy undead’ – one of my pet peeves… female undead should be just as gross and gnarly as their male counterparts).

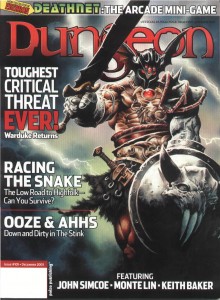

The cover for issue 105 is nostalgia heaven, plain and simple. Warduke was one of my favorite action figures growing up (him and Force Commander from the Micronauts ) so seeing him posing like he’s on the cover of an Iron Maiden album all but guaranteed I’d pick up a copy of the magazine. Reynolds not only does the venerable Warduke justice, he also gives him a few cycles of steroids – just in case your PC actually thought they could stand up to the ‘duke and survive.

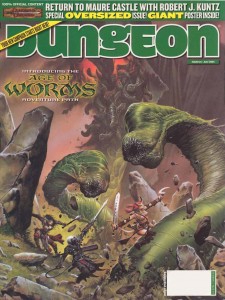

Reynolds’ cover for Dungeon 124 is at a different scale than he typically works, and it’s so energetic and vibrant it makes me wish he would use it more (spoiler: he uses it for the final cover and its excellent). This painting is a perfect snapshot of what I picture when the PCs are squaring off against huge foes. There is a real cinematic quality to the action, and the spectral image of Kyuss rising in the background almost makes it look like a movie poster (just imagine – The Age of Worms saga featuring the voice of Benedict Cumberbatch as Kyuss!).

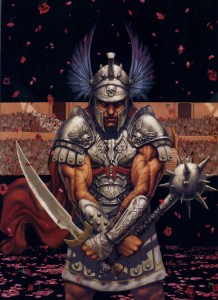

Marc Sasso invokes the blood soaked arena sands of a fantasy version of Rome for his cover of Dungeon 96. Sasso captures the high drama of the moment by keeping the viewer’s gaze in constant motion from one detail to the next: the gently falling roses foreshadowing the future spray of blood, the death motif of the armor, the grim look on the gladiator’s scarred face, and the telling inscription on the blade, ‘hate and kill’. Like Mark Zug’s bandit leader, this is the kind of painting that radiates personality and inspires player characters (and I’ve got the perfect miniature for it!), even if it wasn’t intended to.

I love the thick, colorful lines and painterly style of artist Chuck Lukacs, so I had to include his beholder in this list. While issue 97 was the only cover he made for the magazine, his illustrations festooned both Dungeon and Dragon during the 3e period (and because his style is so distinct, are easy to recognize), and helped to define the look of the era. I’ve never seen a beholder rendered quite like this before, and I really dig the almost globular treatment of the protruding eyestalks.

This issue was also a major milestone for the magazine: it contained Life’s Bazaar, the opening chapter of D&D’s first adventure path. The rest, as they say, is history.

Other than the iconic monsters of the game, no other image can singularly sum up the dungeons of D&D as well as the green devil portal from the adventure Tomb of Horrors. Artist Dave Studer gives Erol Otus’ classic illustration the sculptural treatment for the cover of issue 116 and it is simply amazing. One of the things I really liked about the 3e hard covers (especially the Monster Manuals) was their sculptural design. By drawing on that aesthetic, Studer visually reminds us that the entirety of the game’s editions are our playground and a source of inspiration. I’m not sure how big the original is, but I can’t help but think it would make a kick-ass door knocker for my house.

Artist Dan Scott never fails to impress me with the consistency with which he captures the spirit of adventure that defines D&D. This pair of Scott covers are perfect examples of that ability. Both capture an adventure in progress, and invite the viewer to fill in the story themselves – one of the highest achievements of fantasy illustration.

The cover of Dungeon 122 shows an elven rogue ambushed by lizardmen outside of their crumbling and vine choked, jungle temple. The great thing about this painting is how Scott tells the story through the use of his color palette. Aside from the violence, Scott’s choice of colors for the elf clearly mark him as an explorer and intruder while the naturalistically colored lizardmen are obviously native to this exotic land.

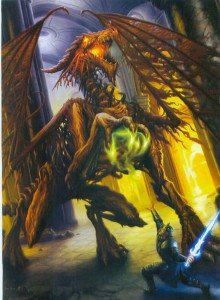

Scott tells the story of Dragotha the dracolich on issue 135 through the use scale. Again, the adventurer (a paladin this time) is clearly an intruder, only this time its David and Goliath retold. The adventurer is dwarfed not only by his opponent, but also by the massively pillared hall. Unless the paladin has some clever edge in this fight, the best he can hope for is a quick death.

As a side-note, while some might label the dracolich as one of D&D’s fringe monsters, I’ve always thought of it as part of the core brand. It was on the cover of both Pillars of Pentegarn, an endless quest book that helped draw me into the game, and Spellfire, one of the first D&D novels I read. It’s not surprising that I used a dracolich for my first real, recurring villain in the 2e game I ran in grade 8 and 9 (it lived in undermountain and its soul was eventually housed in a mechanical golem-like body).

The cover of Dungeon 146, by Tomas Giorello, is truly a beautiful painting and work of art. It wears its neoclassical inspiration on its sleeve, which isn’t a source you often see fantasy illustrators drawing from, and I love that. The sober colors, highly textural folds of fabric, and strong diagonal lines bring to mind David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps. Giorello’s work is so nice to look at it’s easy to forget the kraken tearing through the wreckage of a ship in pursuit of the pirate captain. It’s really a shame that Dungeon had stopped the practice of dedicating a page of the magazine over to an unadulterated version of the cover art, Giorello’s work deserves it.

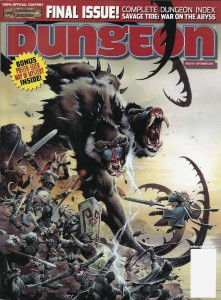

Dungeon 150, the final print issue. Wayne Reynolds’ cover, depicting the climax of the final adventure path of the magazine, seems appropriately cathartic for the occasion of the magazine’s cancellation. For the epic fight against Demogorgon, prince of demons, Reynolds pulls together all of the ‘iconics’ that Paizo used during their stewardship of Dungeon as stand-in adventurers for covers and illustrations. It sums up the body of work very well, and the iconics’ steadfastness in the face of the suicidal melee assures fans of the magazine that Dungeon will not go out with a whimper, but with a bang (fortunately we all know how well everything turned out for Paizo).

Classic Monsters: Coffer Corpse

May 25, 2012Note: ‘Classic’ is a pretty subjective term, when I use it here I mean to say: monsters that have survived through the editions of D&D that I think are cool. In this series of articles I look at the development of a classic monster over time and try to add a ‘crunchy’ piece of my own to the creature’s canon.

I’m posting this second  installment of Classic Monsters as part of The Going Last Gaming Podcast’s May of the Dead blog carnival. There has been a shameful shortage of undead on Ménage à Monster, and the blog carnival seemed like the perfect opportunity to rectify that (and a great excuse to write another article in this series – the eye of the deep was getting pretty lonely).

installment of Classic Monsters as part of The Going Last Gaming Podcast’s May of the Dead blog carnival. There has been a shameful shortage of undead on Ménage à Monster, and the blog carnival seemed like the perfect opportunity to rectify that (and a great excuse to write another article in this series – the eye of the deep was getting pretty lonely).

I first encountered the coffer corpse lurking in the pages of the Fiend Folio and was instantly drawn to the fantastic Russ Nicholson illustration (click on the images to view full size). While the coffer corpse doesn’t get the same kind of fan recognition as the death knight (also introduced in Fiend Folio), I’ve always felt its low power level and unique mechanics gave it a certain charm. Like the Monster Manual’s vampire and mummy, the coffer corpse was also one of the few undead creatures in the game whose background jived with the mythology of the restless dead in horror films. While arguably a little obscure, the coffer corpse’s great mechanics, art and story combine to make the monster a classic.

Origins

Like many of the monsters in the Fiend Folio, the coffer corpse first saw print in the pages of White Dwarf as part of the ongoing Fiend Factory column (issue 8, 1978). In its infancy White Dwarf was a general gaming magazine with a focus on D&D, which makes sense given that Games Workshop (the company that produces the magazine) was at that time the UK distributer of the D&D game. Since the AD&D Monster Manual had only just been published in the UK, the creatures in the Fiend Factory column were created for the OD&D game.

Like many of the monsters in the Fiend Folio, the coffer corpse first saw print in the pages of White Dwarf as part of the ongoing Fiend Factory column (issue 8, 1978). In its infancy White Dwarf was a general gaming magazine with a focus on D&D, which makes sense given that Games Workshop (the company that produces the magazine) was at that time the UK distributer of the D&D game. Since the AD&D Monster Manual had only just been published in the UK, the creatures in the Fiend Factory column were created for the OD&D game.

The White Dwarf version of the coffer corpse sets out the parameters for all of the incarnations of the monster to follow. Cursed to undeath by incomplete or botched funeral rites (or as the author puts it, when a corpse fails to return to its ‘maker’), these animate corpses are often found floating on waylaid grave barges. The coffer corpse attacks by choking the life out of its victims, and can only be harmed by magic weapons (which inflict half damage). If the creature is struck with a normal weapon, it falls to the ground, apparently destroyed, only to rise up a round later in a display so horrible NPCs must succeed at a save vs. fear or flee in terror (the editor, Don Turnbull, notes at the end of the entry that this is probably an error and that PCs should also have to save vs. fear as well).

The coffer corpse was created by Simon Eaton, a name I’m not familiar with, as the only other credit I can find attributed to him is the witherweed (also featured in the Fiend Folio).

1st Edition

The coffer corpse was given an AD&D makeover for its inclusion in the Fiend Folio (and D&D canon). Its origins remained unchanged but a few of the monsters abilities were tweaked. Magic weapons do full damage to this version of the coffer corpse, and it falls to the ground if it is hit for 6 or more points of mundane weapon damage (instead of the ambiguous “if struck on the head” of the previous version). When the coffer corpse reanimates, all who are in melee must save vs. fear, not just NPCs. Additionally, the strangulation attack of the coffer corpse is upgraded from a simple 1d6 attack to one that inflicts automatic constriction damage each round, which is especially deadly since “nothing will release the grasp of the coffer corpse once it has locked its hands in place.”

2nd Edition

The coffer corpse next appears in 2e’s Fiend Folio Appendix for the Monstrous Compendium. While generally identical to its 1e incarnation, most of its abilities are expanded and explored in greater detail: this coffer corpse has resistance to some weapon types (magic slashing weapons inflict normal damage with no bonus, blunt weapons inflict full damage and piercing weapons inflict half damage), and it is possible to break free of its strangling grip (but with a strength of 20 it’s still very difficult).

The most important addition to the coffer corpse in 2e is an attempt to utilize the creature’s origins as a way for clever players to defeat it: “If the unfinished death ritual which binds the coffer corpse to undeath can be completed, the creature will be released and effectively destroyed.” The mechanics of how players might go about discovering and acting on this information is left to the DM’s discretion (and this bit is buried in the habitat/society section of the write-up), which is too bad since I think this is where the coffer corpse’s true potential as a classic monster lies.

3rd Edition

The coffer corpse never saw an official release for 3e. The Fiend Folio is generally regarded as a mixed bag and, in an effort to excise some of D&D’s sillier monsters from the game (the flumph is almost a clichéd example), many great monsters from this book, including the coffer corpse, were not updated for this edition of the game. However, Necromancer Games included the coffer corpse in their Tome of Horrors book, which updated just about every monster from 1e that WOTC had left behind (an admirable effort – though I think the carbuncle should have been abandoned to the dustbin of history). This version is more or less a direct translation of the coffer corpse from the Fiend Folio for 3e rules (damage reduction instead of immunity to normal weapons, and standard grab and constrict rules for the coffer corpse’s strangulation). It is a solid adaptation but, by sticking so closely to its 1e incarnation, I think it was a missed opportunity to expand and clarify the ‘unfinished funeral rite’ that the 2e version touched on (also, why they maintained the 25% chance for the coffer corpse to wield a weapon from previous editions is a mystery to me – the fact that the monster strangles people to death is what makes it interesting).

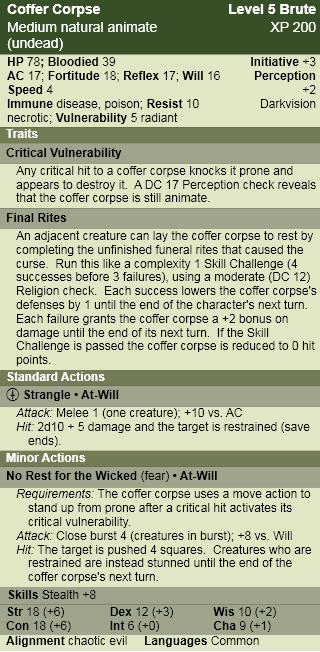

4th Edition

Not having a memorable appearance in 3e, and with 4e’s proliferation of low level skeleton and zombie breeds, it is hardly surprising the coffer corpse is absent from this edition. I do think that 4e’s skill challenge mechanic is particularly well suited to simulate the pitched struggle of a Cleric trying to complete funeral rites while the undead monster strangles her companion, which makes the coffer corpse the perfect candidate for entry into 4e’s canon.

Coffer Corpse

Barred entry into the afterlife by incomplete funeral rites, the coffer corpse is cursed to a restless eternity, its only desire to squeeze the hated spark of life from anything that crosses its path.

Lore

Religion DC 15: Although they superficially resemble zombies, coffer corpses aren’t animated through necromantic rituals, but are created as a result of a divine curse. Their deathlike grip is exceptionally strong, making escape all but impossible once the coffer corpse has wrapped its bony fingers around your throat.

Religion DC 20: Cursed by an incomplete funeral ritual, a coffer corpse is difficult to destroy, often springing back to life only moments after being felled. Only by completing the creature’s burial rites can the curse be lifted and the tortured soul granted peace.

Encounters

Coffer corpses can be encountered floating aimlessly in a waylaid funeral barge, slumped over a half dug grave, or lying in a coffin awaiting the completion of an interment ritual that never comes to pass. They are often part of a group of undead, created as part of the larger tragedy that interrupted the creature’s funeral.

Coffer Corpses in Combat

Every moment of existence is torture for a coffer corpse, so these undead monsters fight without regard for their own well-being. Even as they strangle and destroy they often liplessly whisper for release in their victim’s ear.

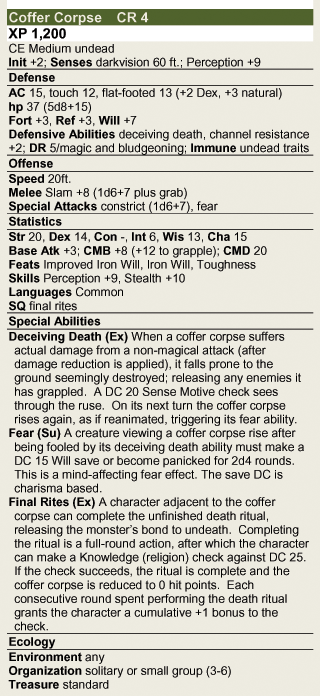

Pathfinder

For those looking for a classic interpretation of the coffer corpse, Necromancer Games has updated their 3e book Tome of Horrors Complete, and the coffer corpse, for the Pathfinder game (and since its part of the OGL you can get this version at the Pathfinder System Resource Document). If you like the ideas in my 4e version of the monster though, I have used it as the blueprint for this Pathfinder translation of the coffer corpse that builds on the creature’s 2e presentation. The flavour text and lore from the 4e monster are system neutral enough to be used as is.

The Best Dungeon Covers: 1-75

April 23, 2012Last month marked the 200th issue of Dungeon magazine, which is quite a milestone (even if I do still mourn the loss of the Dungeons and Dragons print magazines), and as far as tabletop gaming magazines go, one that I think has only been achieved by White Dwarf and Dragon.

Just as I did to celebrate Dragon’s 35th anniversary last year, I thought I would go back through the archives and highlight the best examples of cover art Dungeon magazine has to offer (the best Dragon covers are here: 101-200, 201-300, 301-fin). Like my previous retrospective, it was difficult narrowing down favorites (and I have no doubt that others will disagree with my choices) especially since Dungeon covers, by nature of the magazine’s adventure oriented content, tend to favor my favorite subject matter – monsters.

I’ll admit up front that Dungeon has never held the same fascination for me as Dragon. While in print, I never had a subscription to Dungeon, since I wasn’t sure if future adventures would be suitable for my players, or ones I would be interested in running. However, I made a point of checking each instalment out, and bought more than a few. In retrospect, I can see that I used the latest issue of Dungeon as an excuse for a monthly visit to one of my neighborhood hobby stores, and seeing the covers of all these Dungeons now instantly takes me back to the Hobby Shack, Shooting Star Comics and Leisure World (come to think of it, there were a lot more comic and games stores back then). So even though I was never as devoted to Dungeon as I was to Dragon, the cover images are now the wallpaper in the background of many fond memories and gaming ‘firsts’.

Click on the images to view in full size.

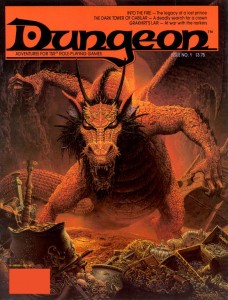

There’s no better place to start than at the beginning, and Dungeon started with a bang. I used to have a poster of this Keith Parkinson painting up on the door to my closet, where it remained until I left home for graduate school. I used to stare at that picture waiting to fall asleep, and it will always be the first image that comes to mind when I think of a dragon’s horde of treasure (I absolutely love the stolen galley in the background – now that is some serious loot!). The focus of the work, the red dragon Flame, would become one of Dungeon’s most iconic villains, appearing in several adventures, including issue 200’s Flame’s Last Flicker. Parkinson’s painting perfectly captures the majesty and menace of its subject, and I think this cover is at least as responsible for Flame’s notoriety as the adventure within (Into the Fire).

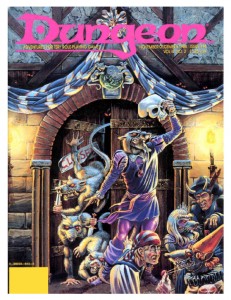

Flame next appeared on Carol Heyer’s cover for Dungeon 17. Heyer uses Parkinson’s cover as a model and zooms in for a focused portrait. I love how her work captures the covetous nature of dragonkind and the accusing stare she gives Flame tells the reader that it would be dangerous to come between the creature and its gems. Lately I’ve found myself missing the ‘tufted’ look of old-school red dragons, and this cover scratches that itch nicely.

This era of Dungeon featured a prolific number of cover paintings from Jennell Jaquays (then known as Paul). All of her work evokes a great sense of adventure, though piece each achieves this through a different emotional palette.

The cover of issue 14 is just so much fun it brings a smile to my face every time I look at it. This is the kind of madcap, funny/deadly encounter scene that memorable adventures are made of. The hamlet-esque wererat with the skull mask is awesome, but my favorite figure is the disgusted partygoer who has just realized the object of his amorous advances is a verminous monster. Its paintings like this that fostered my love of urban adventure in D&D.

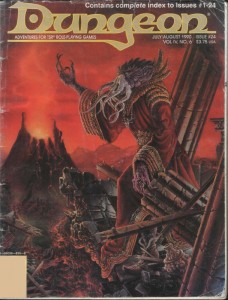

Her painting for Dungeon 24 abandons whimsy for a dark and moody atmosphere. The backdrop, with its crumbling columns and sinister volcano, is almost apocalyptic in tone – a suitable home for one of D&D’s most feared monsters to lord over. I have always liked this visual incarnation of the mind-flayer, with its gnarled, coral-like skin and skeksis style robes. It was a very popular look during the 2e days, but was replaced by 3e’s smooth skinned, cenobite attired version (also cool, but this version is my favorite). Besides having a great cover, this issue is important for another reason. It contains the adventure (which the cover depicts), Thunder Under Needlespire by a very young James Jacobs, a man who would later become Paizo’s editor in chief.

Although Jim Holloway’s art became synonymous with the Spelljammer setting, I don’t think anything he produced can touch Jaquays’ cover for Dungeon 28. The background nebula is not only beautiful it’s also a nice technical achievement and the best representation of the phlogiston that I have seen (if you’re not familiar with Spelljammer, that’s the flammable gas that makes up space in D&D). The crumbling Nautiloid hulk in the foreground drifting towards the planet has a very eerie, Event Horizon vibe to it (even though this issue predates that film by six years). The thing I like most about this painting though is that it sells Spelljammer as a legitimate setting for serious adventures – not just the boxed set with the giant space hamsters.

In addition to painting a cover that made the Dragon list, Bob Eggleton also created this piece for Dungeon issue 19. The summoned death is as frightening as it should be and the background done in cool blues gives the picture a mystical ambiance. The combination is perfect in capturing the spirit of one of my favorite magic items in the game, the deck of many things. The icing on the cake is that Eggleton styled the card in the painting after the deck of many things set that came as a bonus in Dragon a few months prior.

Thomas Baxa, the artist responsible for the cover of Dungeon 29, is something of a lightning rod for criticism of the 2e era’s art. Now, I’m not a fan of his work in general, but I don’t dislike it out of hand, and in spite of the haters, he has created some exceptional works in his career with Dungeons and Dragons (his undead illustrations are delightfully weird and gruesome). This painting, of an abishai being summoned by a cursed book, is his best. Baxa’s rejection of naturalistic colors in favor of bright (almost garish) reds and purples brings the painting into the realm of the surreal, and I can’t help but be reminded of Erol Otus. I’m not sure I would feel the same about his technique with a different subject, but a blighted text ripping open a gateway to the netherworld? This could easily be the cover of a Clark Ashton Smith collection.

The next covers I’ve chosen are linked not just by their nautical theme, but because they are fantastic examples of a painting’s ability to tell a story and engage the viewer to fill in the blanks.

Issue 34 by Peter Clarke uses a reverse angle of the protagonist for a wickedly sinister horror movie composition. It’s not surprising then that the story this painting evokes plays out in my mind like a film: the adventurer tugs his rowboat ashore, unaware of the skeleton rising from the dunes behind him silently. With sand slowly spilling from its empty eye sockets, the undead beast raises its rusted scimitar and…

Alan Pollack’s cover for Dungeon 40 is less of a film and more of a perfect snapshot of movement frozen in time. Pollack uses the perspective so well, you can almost feel the pressure of the water around you as the koalinth hang suspended with their pilfered treasure (this is one of the only illustrations of these creatures I have seen). I also like the opportunistic sharks circling in for an easy meal. The need for dynamic composition in fantasy illustration is a point hammered home by art directors over and over – this is how it’s done.

Another cover by Peter Clarke, for issue 43. Backlit by the fiery blast from an impossibly massive dragon, an adventurer and githyanki struggle for a fabled silver sword. Freaking epic. That is all.

Earlier, it may have sounded like I dissed Jim Holloway, but I really like his work in the right context (his style defined the Paranoia game, those Tales from the Floating Vagabond ads were awesome, and yes he had some great Spelljammer pieces as well). Case in point: this cover for Dungeon 60, overflowing with character. I have a tendency to take myself too seriously, and Holloway is the cure for that, reminding the viewer that the game is supposed to be fun. The best part about the humor in this painting is that it doesn’t descend to the level of a ‘joke’ cover. Instead, what I think Holloway captures here is how the game actually plays out at the table. You’ve got a disparate and loosely organized band of adventurers searching for treasure(and I love the implied relationships there – the swordswoman shooting daggers at the halfling for hamming it up), completely oblivious to the kuo-toa war party sneaking up behind them (who obviously made their Stealth or Surprise checks – depending on which edition of the game you’re playing). The bio-luminescence is a nice touch too. I’m not the only one who thinks this issue is boss – Outsyder Gaming wrote a whole series of articles on it.

Jeff Easley only ever made a single cover for Dungeon magazine, issue 69, and I had to include it here. I don’t think it’s his greatest work (his dragon covers are much more impressive), but I included it for two reasons. First, it is just so Easley (if I can use that as an adjective). What I mean is it’s so indicative of his trademark style that you can tell it’s an Easley painting from a mile away. The highly sculptural figures, the plush rendering, the earth tones accented with bright colors… you know, so Easley (and let’s face it, an average day for Easley is a great day for anyone else). I also included this painting in the list because it showcases how different an animal a Dungeon cover is to one created for Dragon magazine. Dragon covers might have to portray a vague theme, but generally the artist is free to follow their instincts. Dungeon covers on the other hand are much more structured. Their function is to represent one of the adventures inside in a very literal and concrete way. The cover doesn’t just have to look good, but it also has to inform the viewer about the magazine’s content. Even a big name in the TSR art department can’t phone it in – this cover accurately depicts the Doom Brigade, one of the teams of antagonists from the adventure Sleep of Ages (a group of helmed horrors with two-handed swords and a flameskull in the service of an elder orb beholder).

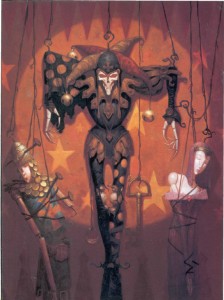

Undead and puppets, two creepy tastes that taste great together. Incredibly, this particular combination has been used for two Dungeon covers. First, on Dungeon 64 by Mark Nelson – who takes full advantage of his experience working on Clive Barker’s Hellraiser comic. It’s really the details in this painting that elevate it from creepy into a work of true horror: the intricate and painstakingly constructed clockwork marionette mechanism hints at the obsession of its creator; the desiccated flesh of the corpses contrasts against the finery of the puppets’ fancy dress; and the awkward way the dance partners are forced to hold one another brings the wrongness of the scene to a fever pitch.

The second such unsettling cover is for issue 75, by Brom. While Brom’s early work for TSR (especially his Dark Sun illustrations) was very much in the vein of Frank Frazetta, this cover represents a shift in his style towards a darker, more gothic look. I love Brom’s work in any mode, but unfortunately I think this shift (combined with his independent success) took him off course from the branding of D&D as heroic fantasy. At the end of the 2e era, Brom’s work was found in fewer and fewer products, completely disappearing from D&D (except for the odd magazine cover) by the time 3e rolled out. There is a lot of talk lately about what the art of the next edition of D&D should include. If it is to be as inspiring as the art of earlier editions, then Wizards of the Coast needs to bring visionaries like Brom, and the other artists I have highlighted here, back into the fold. It’s worth the high price tag.

In the nest installment I’ll look at the latter half of Dungeon’s print run, the 3e era.

Vote for Ménage à Monster Today!

April 19, 2012 Just a reminder that today is the day to vote for Ménage à Monster to win the RPG site of the year contest. Just follow this link and vote for yours truly:

Just a reminder that today is the day to vote for Ménage à Monster to win the RPG site of the year contest. Just follow this link and vote for yours truly:

http://stuffershack.com/reader-voting-day-4-of-5-for-the-2012-rpg-soty/

Don’t worry, the blog hasn’t sunken (completely) into a mire of self-promotion. A real update is on the way, in celebration of Dungeon magazine’s 200th issue (hint: it’s got some fantastic art).

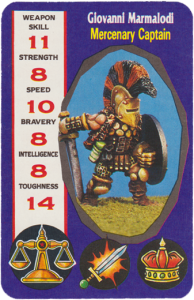

More Citadel Combat Cards

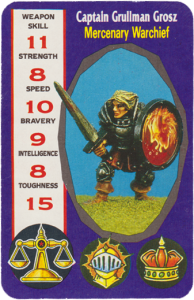

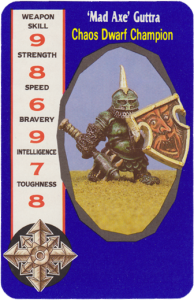

April 4, 2012Last May I wrote about my love of the golden age of Citadel miniatures (the ‘slotta’ era – late eighties and early nineties), inspired by Ben of Darkly Through Glass’ fantastic collection of scanned Citadel Combat Cards. Although that site is now dormant, Ben is back with a new blog, Fantasy3D, and one of the first things he has done is upload the rest of his combat cards, completing the set (with the Dwarfs and Warriors decks). Seeing all the cards together warms my little lead coveting heart, and having them at my fingertips is an invaluable resource. These cards are a nostalgia trip, painting guide, and collector’s list all rolled into one. Ben’s scans are so immaculate I almost don’t regret losing my well-worn and beat up decks. I recommend downloading them yourself, but here are a few of my favorite dwarves and warriors (click for full size).

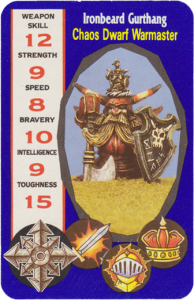

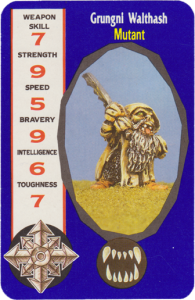

When I was younger I had a bit of an obsession with the realm of chaos line, so it’s hardly surprising that I have a soft spot for the chaos dwarves as well. I should have bought these when I was a teenager. These two are from the iconic Chaos Dwarf Renegades boxed set (featuring an equally iconic John Blanche painting), which, if it does come up on ebay, is insanely expensive, so I doubt I’ll be adding them to my collection anytime soon. I can’t really argue, but I blame the high demand on the lame redesign Games Workshop did on their newer Chaos Dwarves (the ones with the silly hats as tall as their bodies).

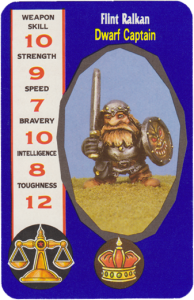

One of my favorite features of the painting style of this era are the cool, freeform designs that took advantage of Citadel’s trademark plastic shields. It really makes each model stand out, and emphasizes a ‘lived-in’ implied setting where soldiers recycle equipment from fallen foes (kind of like D&D). Although I never had the mini, Flint inspired my friend’s character ‘Ralkan the Mighty’ in the first campaign I DMed.

There are some miniatures you track down just to have in your collection and there are others you want so you can build a D&D character around them. This is one of the latter. Despite being from a boxed set, the Heroic Fighters of the Known World (also John Blanche illustrated) are far easier to come by than the Chaos Dwarves. I was able to pick up Giovanni cheaply last year and I’ve been itching to play the mighty thewed gladiator ever since.

So often when I’m browsing through my collection I find myself wanting to make characters for the miniatures, instead of looking for a miniature that suits a character. If there is any reason to call this period Citadel’s golden age, this is it.

It Came from Toronto After Dark: The Innkeepers

February 16, 2012These It Came from the DVR articles are going to be a little bit different. As an early Christmas present to myself, I picked up a festival pass to the Toronto After Dark film festival. So the first difference is that these are new movies, on the big screen, instead of old ones and niche programming on the small screen. The second difference is that these are going to be short. I’ve got eighteen films to see in seven days (as well as dressing up for the annual zombie walk), so I’m not going to have a whole lot of time to write, and I want post these while the blood is still fresh.

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration, but most of the films it showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

The Innkeepers

This film tells the tale of the last days of the Yankee Pedlar Inn, an old New England hotel with an illustrious past but dwindling clients. For employees and amateur ghost hunters, Claire and Luke, the hotel’s closing weekend is also their last chance to finally capture proof of the Inn’s supernatural activity. They will soon wish they had left the old building in peace.

Great Characters, Sub-Par Scares

I had high hopes for the screening of The Innkeepers. A good old-fashioned ghost story felt like the perfect note to end an incredible festival. Unfortunately, Ti West’s film falls disappointingly flat. The shame is, it isn’t terrible and I can’t help but imagine the great movie it could have been. The Innkeepers has a lot in its favor; it just seems that somewhere along the line West forgot he was making a horror film.

The film benefits from some great characterizations, especially by Sarah Paxton and Kelly McGillis, who are genuinely funny (and in spite of what some people may think, comedy is important in a horror film – it breaks the tension and allows you to sympathise with the characters). If you’ve ever had to work a minimum wage job in the service industry, you’ll sympathize with Paxton’s character Claire who manages to capture that perfect blend of boredom, resentment, and lack of ambition that comes with the job. There is a deceptively simple scene in The Innkeepers where Claire has to take out an extra heavy garbage bag to the trash that captures that feeling absolutely perfectly. The banter between her and her co-worker is great, and helps to pull the viewer into their world. The funniest lines in the film though are given to McGillis’ character, an aging, bitter icon trying to reinvent herself as a new age healer. I’m sure she drew on her lifetime spent in film and television to provide the acidic edge that makes the character so memorable.

I appreciate the amateur ghost chaser angle to The Innkeepers, as it makes the film timely (as a comment on recent reality shows like Ghost Hunters), while at the same time linking it to such classic films as Poltergeist and The Haunting (and less classic films like Hell House and Amityville 3-D). It’s a promising set-up and the back story of the film’s ghost is tragic and interesting enough to hook the viewer in and keep them watching.

The pacing is very slow, which isn’t bad in itself as the characters are interesting, and you definitely get the sense that the film’s energy is building for a big climax. Unfortunately, West never delivers on that big climax and the buildup is wasted. Sure, there are some creepy, tense moments in there, but it never culminates in the big payoff you would expect. In the Q+A after the screening, West expressed that he wanted to create a film where the existence of the ghost was ambiguous, and that the audience could walk away with either a mundane or supernatural explanation. That’s a pretty cool concept, but one I don’t think The Innkeepers accomplishes, or even tries to. The film is shot in such a way that the audience sees more than the characters do (and this technique actually generates one of The Innkeepers’ better scares), so there is never a question whether the ghost is real or a figment of Claire and Luke’s imaginations. Instead of making a psychological horror film where the audience questions their own senses and experiences the fear and doubt of the characters, West has made a slow moving ghost story that isn’t very frightening.

I’ve also got to call out The Innkeepers for its depiction of asthma. As a person with chronic asthma, it’s always bothered me how the condition is depicted in film and television. The Innkeepers is hardly the worst culprit (that’s probably The Goonies), but since I’ve lived with asthma for most of my life, I feel a strange kind of ownership of it, and it drives me crazy when filmmakers misrepresent the illness so badly. First, asthma can be controlled with regular medication. Attacks that leave you panicked and gasping for air are dramatic and scary, so I understand why storytellers want to make use of it, but should be (if you aren’t sick, and are taking you medication) relatively rare. If I have several attacks like that in the same day (most movies have four or five), then something is seriously wrong and I’m going to head for the emergency room immediately (the equivalent would be a character with diabetes falling in and out of diabetic coma throughout the film). That’s a plot point you should only hit once. But it’s hardly surprising that Claire has so many asthma attacks in The Innkeepers when I don’t think I’ve ever seen a character with ‘movie asthma’ take their medication properly. After using an inhaler, if you immediately breathe out, you’re expelling the medication from your body before it has a chance to act (which is why some asthmatics use a tube that looks like an ‘inhaler bong’). I’ll admit that The Innkeepers isn’t entirely deserving of this ire, but West makes use of asthma enough that his film is far from exempt from my ranting.

The Innkeepers is not recommended as a horror film. It’s not a bad movie, but if what you are looking for is a scary ghost story you’re much better off looking elsewhere (Absentia, Insidious and Paranormal Activity are all great choices). If you are a huge fan of Ghost Hunters and have a hankering for an hour and a half episode with better acting and good dialogue however, then The Innkeepers may be what you’ve been looking for.

RPG Goodness

Ghosts are one of those creatures that are very hard to translate into D&D terms in a way that emulates how hauntings are depicted in film and television (including The Innkeepers). Throughout its history, each edition of D&D has dealt with ghosts differently and used different mechanical approaches to representing the tropes associated with hauntings: tormented spirits repeating activity in a loop, unfinished business, and revenge.

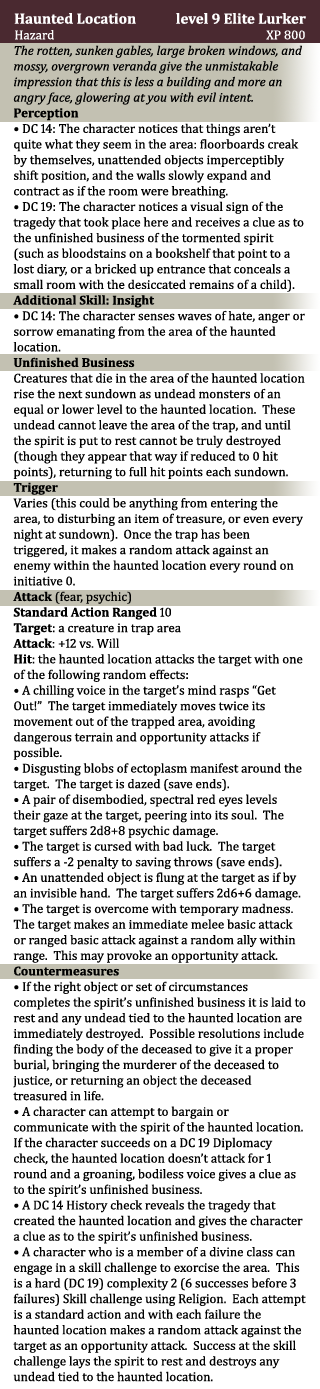

Old-School ghosts can possess the living, but are otherwise just powerful monsters (although possession can be used by DMs as a way for ghosts to try and bring closure to unfinished business). During the 2e era ghosts are given a much fuller treatment in the Ravenloft campaign setting, especially the Castle Forlorn boxed set, which features a castle that loops through different periods of time to tell the story of the tragedy that took place there. 3e reimagines the ghost as a template that modifies existing creatures, which means that the undead spirit more directly reflects its living self, with the same abilities and the addition of ghostly powers. My favorite part of the template though, is that ghosts reform a few days after being destroyed – the only way to truly rid an area of a ghost “is to determine the reason for its existence and set right whatever prevents it from resting in peace”. 4e abandons the template idea and treats ghosts as straight monsters (which is fine – the ghosts of commoners should be just as scary as the ghost of an adventurer). The Open Grave supplement for this edition also introduces the concept of using traps and skill challenges to mechanically represent hauntings in the game. It’s a fantastic idea, but I feel the sample skill challenge in the book is too abstract for the action of a ghostly adventure, and the traps listed don’t give the same sense of unfinished business that the ghosts from 3e embody. The haunted location trap is my attempt to bridge that gap.

Haunted Locations

Sometimes the location of an especially tragic suicide or gruesome murder becomes infused with the anguish of the spirit of the deceased, too tormented by its own pain to move on to the Shadowfell. The location becomes a beacon for the undead, and until the tormented spirit is laid to rest, is a perilous place for the living to dwell too long.

A haunted location requires more work on the DM’s part than a normal trap or hazard. The DM must determine ahead of time what tragic event caused the site to become haunted, what object or set of circumstances will lay the spirit to rest, and what triggers the spirit to become active.

The haunted location can take the form of anything from a single room in the dungeon of a castle to a dilapidated mansion on a lonely hill. This trap works best when combined in an encounter with a group of undead creatures of the appropriate level. These monsters are all that remains of the spirit’s past victims, now absorbed into the haunted location’s malevolence.

It Came from Toronto After Dark: The Woman

February 11, 2012These It Came from the DVR articles are going to be a little bit different. As an early Christmas present to myself, I picked up a festival pass to the Toronto After Dark film festival. So the first difference is that these are new movies, on the big screen, instead of old ones and niche programming on the small screen. The second difference is that these are going to be short. I’ve got eighteen films to see in seven days (as well as dressing up for the annual zombie walk), so I’m not going to have a whole lot of time to write, and I want post these while the blood is still fresh.

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration, but most of the films it showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

The Woman

This is a disturbing film with a bizarre premise. When a conservative, small-town family man encounters a cannibalistic feral woman in the woods, he decides to capture her and bring her home to his wife and three children so they can civilize her as a ‘family project’. Chained up in the barn, the presence of the dangerous feral woman exposes a darkness in the family that quickly erodes its whitewashed, seemingly ‘normal’, façade.

Dark Social Commentary

I should preface this review – I’ve never seen the film that precedes this one, The Offspring, but the two films are only loosely connected. The Offspring doesn’t contain any plot information critical to this film, and while the movies can be viewed as a series, The Woman also stands on its own.

The Woman cannot be easily classified. I wouldn’t call it a horror film, though there are moments when it is truly horrifying. There is humor in The Woman, but I’d hardly call it a comedy (even a black comedy). I can’t say that I enjoyed watching the film, but I also think it is a movie that is worth watching. Director Lucky McGee keeps the audience on their toes, playing with our expectations and throwing the audience a curve ball whenever you think you’ve got this strange tale sorted out.

Sean Bridgers’ portrayal of family patriarch Chris Cleek, as a sort of diabolical Ned Flanders who begins to lose control as his monolithic authority cracks, is so perfect for the film it was almost uncomfortable seeing him speak after the screening. In the Q&A, Bridgers had a very interesting view of his character when asked about the role. He said that although he was nothing like Chris Cleek, he was still able to draw on some dark, buried part of himself to fuel the role. It’s the kind of observation that I think applies to the whole film and its relationship with the audience. There is some pretty heavy violence in The Woman, including a few very uncomfortable scenes of domestic abuse and rape. Given the way that the ‘torture porn’ trend changed the landscape of horror films a decade ago, I think that McGee is confronting the audience with the ugliness of our dark psychological bits, rather than titillating them the way other horror traditions do. It’s a fine line between glorification and commentary, and everyone has a different sense of that boundary, but to me Lucky Mcgee accomplished his goals without crossing that line.

Even though her character has no real dialogue in the film, Pollyanna McIntosh gives an equally gripping performance as the titular feral woman. I was impressed with her ability to occupy the physicality of the role, and her glazed, sullen stare into the camera infuses the character with the aura of a caged animal. If Chris Cleek stands in for the controlled, oppressive violence that underlies modern society, then the feral woman reminds us of the uncontrolled brutality of the natural world. Even if the audience is cheering for the woman by the film’s climax, I’m not sure that McGee is presenting her as a viable alternative to the Chris Cleeks of the world. It’s a grim portrait of humanity that places us in a tug of war between these two poles, as savage hunters who have the choice of preying on our family units or of preying on everything not joined to us by family.

There was some controversy that came out of the Sundance festival regarding The Woman, including people walking out of screenings, which is understandable if the audience isn’t prepared for the content, but I think this has more to do with the context of Sundance than the film being too appalling to sit through. After a week of seeing decapitations, blood, and zombie cannibalism, the shock of The Woman was blunted, even if I was probably just as disturbed by it as the Sundance crowd (as far as I could tell, no one walked out of the screening at Toronto After Dark).

The Woman is recommended, but only if you’re prepared to be confronted by some alarming scenes. I can’t say that you’ll have fun watching it (and it’s about as far from being a date movie as you can possibly get), but The Woman is anything but boring and is sure to provoke a reaction.

RPG Goodness

Much like Father’s Day, the subject matter of The Woman makes incorporating material from it in an rpg difficult (unless you’re making use of a disconcerting amount of the ideas in The Book of Vile Darkness). Once its more controversial elements are removed though, I think the conflict in The Woman can be viewed in D&D terms that highlight the game’s alignment system (I’ll be using the nine-pointed alignment system, since that’s my favorite, not the three alignments of BX or the five alignments of 4e).

I think that the struggle between Chris Cleek and the feral woman is a great example of how the Lawful Evil and Chaotic Evil alignments interact with one another in D&D. It would be hard to argue one of the characters was more or less evil than the other, but it’s clear that each represents a very different kind of evil, as diametrically opposed to the other as good is to evil. For me, this is why the nine-pointed alignment system (that is, an alignment in two parts – the good vs. evil axis and the law vs. chaos axis) works so well – it handles the evil against evil conflict in a way that makes sense and provides clear motivations for NPCs (which makes it useful, the litmus test for any game mechanic). It also provides clear reasons why two good aligned characters might find themselves at odds with one another or why a good aligned party might make a temporary alliance with an evil creature against a common enemy.

Although many may disagree, I’ve never found the nine-pointed alignment system restrictive. Instead, I find its two-axis approach a simple and elegant tool to encourage roleplaying by providing clear motivations for the thinking creatures of the game world. Sure it isn’t foolproof and doesn’t cover every moral quandary a PC might find herself in, but working out the finer points of ambiguous situations is one of the exciting parts of a roleplaying game.

Taking inspiration from the film, here is a sample of practical alignment complications that can be inserted into any version of D&D:

The Enemy of my Enemy is my Friend… For Now

Both Vault of the Drow and the Temple of Elemental Evil (two of my favorite classic adventures) make extensive use of this complication. Warring factions of evil creatures will use any means they have at their disposal to eliminate one another, including a temporary alliance with good aligned adventurers. As distasteful as it is, it might be in the PCs best interest. The common enemy (the most powerful house of the drow, or an evil tyrant, secure in an impregnable fortress, for example) might be too tough for the PCs to tackle on their own, or the evil creatures might possess needed intelligence in order to proceed.

Chaotic Evil creatures will promise anything to obtain the cooperation of the PCs, and if they feel they can gain from it, will attack them as soon as the job is finished. Lawful Evil creatures can be trusted to keep a bargain, but will only agree to terms that benefit them, and will constantly try to subjugate the PCs to their will.

Thanks for the Rescue, Sucker!

Just because an NPC has been imprisoned by the ‘bad guys’ doesn’t make them a ‘good guy’. Obmi, the evil dwarf from the adventure Hall of the Fire Giant King (and reappearing throughout D&D’s history) is the quintessential example of this complication. Sometimes, creatures are imprisoned by evil societies because they are so deviant or destructive that even the morally corrupt can’t stomach them.

The temptation in this scenario is to have the prisoner rampage as soon as it is freed (which is entirely appropriate in certain circumstances), but the complication works much better when the evil NPC cooperates with the PCs against his captors. Later in the campaign, let the PCs discover the horrendous crimes the freed prisoner has committed – a great adventure hook since most players will feel at least a little responsible and will be driven to stop the former prisoner.

Try not to use this complication too often or the PCs will never want to free any captives again.

What We Have Here is a Failure to Communicate

Sometimes different good aligned groups just don’t get along. The different worlds of D&D are filled with good aligned churches that are generally tolerant of one another, but still clash over major philosophical differences (which is fairly optimistic considering how well the sects of Christianity or Islam have gotten along together on Earth). If there is an established church or state religion in the area the PCs are adventuring in, they won’t appreciate the party’s cleric waltzing into their territory and performing miracles for a rival deity (or worse, actively trying to proselytize). While good aligned organizations don’t immediately resort to violence, they will definitely make things as uncomfortable as possible while they are in town. I used the church of St. Cuthbert in this manner in both the Temple of Elemental Evil adventure and its sequel. In both cases the party contained no representatives from the church and was filled with non-lawful types. Even though they wanted the same outcome (the destruction of an evil cult), the Cuthbertines viewed the adventurers as a bunch of rowdy troublemakers while the party viewed the church as a bunch of out of touch windbags trying to tell them what to do.

Rival Schools

Old-school D&D often included groups of adventurers in the wandering monster tables – a concept that Ed Greenwood greatly expanded upon in his Forgotten Realms setting (especially during the 2e era) with its predilection for rival adventuring companies. This concept hasn’t been used all that much in modern D&D (with the exception of the excellent Shackled City adventure path by Paizo), but is a complication worth revisiting. A rival adventuring company need not be evil to oppose the PCs – good aligned NPCs might pursue the same goals as the PCs (stopping an encroaching hobgoblin army, overthrowing an evil cult, or slaying a terrible dragon for example). Rather than brining the two groups together, these similarities cause tension. The rival adventuring company wants what the PCs’ want, only they want to do it first and they have no intention of sharing the spotlight (or the glory and treasure).

Good aligned rivals won’t necessarily attack the PCs, but they aren’t above sabotaging their efforts. In fact, if they are less capable, their bumbling might make things much harder for the PCs (like a failed incursion into a dragon’s lair that makes the creature extra careful and paranoid).

The Long Arm of Justice

Adventuring often means transgressing laws and taboos (like breaking and entering, tomb-robbing, and murder). That means that at some point in a campaign a group of good aligned NPCs is going to want to redress one of these transgressions. There are many remedies these groups seek, but this complication works best if the NPCs aren’t immediately violent or threaten the PCs with imprisonment (they may seek compensation, ask for a favor, or challenge the PCs to complete a gruelling ritual of atonement).

If the PCs are strongly lawful aligned, then the reverse can happen. A group of xaositects, followers of Olidammara, or tricky fey target the PCs to discredit them and take them down a notch. They use pranks, rumours, and theft to spread chaos and vex the PCs.

Monsters in 5e

February 3, 2012 I’ve purposely refrained from posting a lot of speculation about the next edition of D&D until I get to see more playtest information. However, (now I’m about to do the exact opposite) I have been following the news from the D&D experience convention pretty closely and thought I would share some of lead designer Monte Cook’s thoughts on monsters for the next edition:

I’ve purposely refrained from posting a lot of speculation about the next edition of D&D until I get to see more playtest information. However, (now I’m about to do the exact opposite) I have been following the news from the D&D experience convention pretty closely and thought I would share some of lead designer Monte Cook’s thoughts on monsters for the next edition:

We want to work hard to provide actual meaningful guidance on how to be a good DM. We want to embrace the 4E idea of quick prep time. New monster, 5 mins. High level NPCs in 10 minutes. Lots of 4E ideas. Decoupling the idea that NPCs have to advance or be built in the same way as PCs.

We were just talking about throwing in some extra abilities to monsters. So you might have a normal orc, or you might decide to make him a vicious orc that would add an attack that to a nearby creature when the monster dies. That kind of thing could be added in by a DM on the fly because it doesn’t really change the challenge too much or make you rewrite anything. It might give you a little bit of an experience bonus if/when you defeat it too.

These ideas sound promising to me. The way monsters are created and run by the DM are one of the best features of 4e, and it looks like they want to continue that tradition and add in Pathfinder style simple templates (one of that game’s great modifications of 3e). The next edition of D&D is still at least a year away (though probably more) and a lot can happen between then and now, but it’s nice to see the game heading in a direction I like.

For now, I’ll try and refrain from adding to the noise and continue to post about games that I’m playing and daydreaming about (that’s 4e, Gamma World and an upcoming Pathfinder campaign), lest some horrible vilstrak beat me with a ripped up phonebook.

It Came from Toronto After Dark: VS

February 3, 2012These It Came from the DVR articles are going to be a little bit different. As an early Christmas present to myself, I picked up a festival pass to the Toronto After Dark film festival. So the first difference is that these are new movies, on the big screen, instead of old ones and niche programming on the small screen. The second difference is that these are going to be short. I’ve got eighteen films to see in seven days (as well as dressing up for the annual zombie walk), so I’m not going to have a whole lot of time to write, and I want post these while the blood is still fresh.

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration, but most of the films it showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

VS

This superhero thriller jumps headfirst into the story, opening with former teammates Charge, Cutthroat, Shadow and the Wall kidnapped by their arch-nemesis Rickshaw. The four heroes awake in a small town, their powers nullified by a mysterious injection and the populace tied to clusters of high explosives. In order to save the trapped innocents, and themselves, they must complete a series of fiendish tests before Rickshaw detonates the bombs and obliterates the entire town.

Super Hero Action Meets Dark Thriller

VS is another ambitious indie film (I like this trend) that shoots for the moon. It stumbles, but there is genius there, and its sheer ballsy-ness makes me want to overlook the film’s shortcomings. Throwing superheroes into a Saw-esque thriller, is an idea worthy of the Joker (in spite of being a Marvel standard bearer, there are a few DC characters that I like) – so is writing, directing and starring in your film, but Jason Trost manages to pull it off without it looking like a vanity picture.

Because of the look of the costumes, it’s easy to compare VS to Kick-Ass. They may share some similarities, but they are as different as night and day. Both films draw on the ‘real-life superhero movement’ for aesthetic inspiration (hence the similar costumes), and both are a comment on the superhero genre. However, Kick-Ass is a spoof that throws superheroes into our world to send up the inherent ridiculousness of the entire genre (that’s not a slam against Kick-Ass – I happened to like it quite a bit), while VS is a straight superhero tale that draws on the language of horror films to showcase a truly sadistic villain.

And what a great villain to showcase. Veteran James Remar steals the show as Rickshaw, having fun with the role and making it crazy enough to be entertaining but keeping it this side of cartoony (a little over the top is fine – it is a superhero movie). In the Q+A Trost revealed that Remar is an old family friend and did the film as a favor (he liked the script too), which is a good thing for VS; because in the hands of someone the film could afford, I’m not sure the character would have worked.

The tests that Rickshaw puts the heroes through are fantastically evil, and as I mentioned, are very much in the tradition of Saw. There’s also a long tradition of these kinds of traps in comics, particularly the kind that involve difficult decisions that put the heroes’ morals in jeopardy – so the mixing of the two genres works perfectly and is the film’s real genius. Convoluted traps and villains toying with their prey seem completely at home in a superhero film without straining credibility (in fact, the audience expects it), while the dark and gritty horror film trappings tell the viewer that the stakes are much higher than a traditional comic book film and that the body count likely will be as well. This gives the characters’ actions a lot of weight and boosts the dramatic tension much more than you would expect from a film about superheroes.

VS’ second moment of genius, and the part of the film that makes it required viewing for any Hollywood director looking to adapt a comic book for the screen, is how Trost deals with the heroes’ backstory. Instead of spending the first half of the film detailing how the characters acquired their powers, and formed their team, VS just cuts to the interesting part of the story (waking up powerless in a town filled with deadly traps) and trusts that the audience is smart enough to fill in the blanks as the story unfolds. Through short flashbacks and character chatter we’re given all we need to know without lots of boring exposition and wasted screen-time. With VS, Trost proves once and for all that it is possible to make an exciting superhero film right out of the gate.

With the low budget Trost wisely wrote out the costly use of superpowers, and relied entirely on practical effects and stunt work. Normally I would have wanted to at least see someone fly or lift up a car in a comic book movie, but the low-fi look really fits with the dark and grimy atmosphere of the film.

Where VS stumbles is in the film’s pacing. Each of the tests is timed, and the heroes must race against the clock to both overcome the challenges and find Rickshaw before the countdown expires and the whole town blows up. That’s a great device to create natural tension, but unfortunately, every time the viewer starts to worry VS shoots itself in the foot by having its characters get into a drawn out conversations and arguments. There were times when I felt like yelling at the screen, “at least walk and talk, you’re all going to die!” I couldn’t help but wonder as the horrible consequences of the countdown unfolded, that it all could have been avoided if the characters hadn’t been so chatty.

VS is recommended for superhero fans, especially those that are ready for a fresh take on the genre. If, like me, you‘re also a fan of horror films, then VS is happily a chocolate and peanut butter situation. It isn’t perfect, but the high points of VS are well worth the lows.

RPG Goodness

If you play a superhero rpg and want to run a game with the grittiness of the Punisher, but prefer costumes to guns, then VS is the best guidebook you can find. I can totally picture combining the D20 version of Mutants and Masterminds with the list of traps from the Dungeon Master’s Guide to create an adventure very similar to the scenario in the film. Even though the movie doesn’t contain any supernatural elements, I think VS would also work as an introduction to set the tone for a mash-up of Palladium’s Beyond the Supernatural and Heroes Unlimited (I’m not sure if anyone has ever played that – but now that I mention it I kind of want to try it out).

Outside of the film’s obvious inspiration for superhero rpgs, I think that VS highlights an issue in D&D that has been dealt with very differently across the editions of the game – nullifying PC powers. While I don’t think there are any adventures that feature the PCs getting injected with a potion that prevents them from using their abilities, many of the old-school modules are filled with walls that can’t be climbed by Thieves, damage that can’t be healed by the Cleric, and lists of spells that Magic Users are barred from casting to bypass an obstacle (the classic adventure Tomb of Horrors is big on this). Starting with 3e, this kind of adventure design was frowned on and often criticised. DMs were encouraged to work with a PC’s powers rather than work around them. When it comes to this issue I am unapologetically in the camp of the new school. Having your character’s abilities hamstrung just so an adventure can railroad your actions is not fun. I would just as soon have choices I can’t use removed from the game rather than have the illusion of choice.

As strong as my stance is on negating PCs’ powers in adventure design, when it comes to monsters I feel differently. I love the beholder’s anti-magic cone, a ghast’s resistance to turning and the thought eater’s special attacks against psionic characters -even though all these creatures nullify class powers in their own way. This might seem hypocritical, but I think the difference between a monster and an adventure is that the monsters in these cases are rare (although if you had an adventure with nothing but ghasts it wouldn’t be much fun for the cleric – or anyone really), their powers are discreet, and rather than reducing a character’s options to a single path (you can’t pick that lock or use a knock spell, you have to find the magic key in room 18 to proceed), these monsters interact with each of the classes in a unique way that makes them frightening and interesting (a golem is immune to most spells, but a few thematic ones affect it in unique ways).

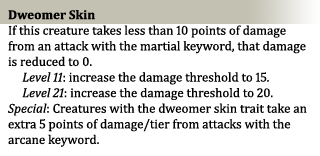

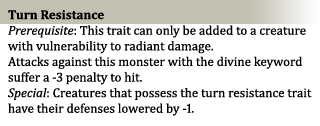

In 4e, which introduced the concept of power sources, this is the feature I expected to interact with those classic monsters, an exciting possibility I thought was wasted (as it turns out, power sources weren’t used for much of anything) – something I’ve lamented before. To remedy this, I’ve created a sampling of traits that can be added to monsters that can transform them into ‘kryptonite’ for certain classes.

Power Sources and Monsters

The following traits can be added to a monster to modify the way the creature interacts with the power sources of the PCs. These traits are minor enough that adding one as-is shouldn’t alter a monster’s level or experience value, although in certain powerful combinations you may instead use it to replace an existing trait or power. Care should be used in placing these traits – there is little point giving a monster anti-magic shell, if there are no arcane characters in the party and the turning class feature will seem pointless if every undead opponent the party encounters has turn resistance.

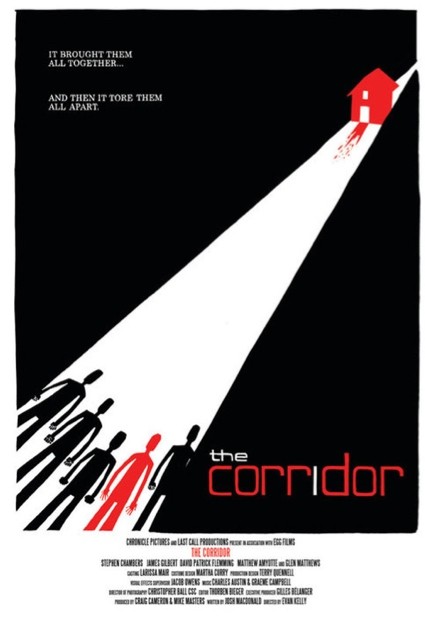

It Came from Toronto After Dark: The Corridor

January 30, 2012These It Came from the DVR articles are going to be a little bit different. As an early Christmas present to myself, I picked up a festival pass to the Toronto After Dark film festival. So the first difference is that these are new movies, on the big screen, instead of old ones and niche programming on the small screen. The second difference is that these are going to be short. I’ve got eighteen films to see in seven days (as well as dressing up for the annual zombie walk), so I’m not going to have a whole lot of time to write, and I want post these while the blood is still fresh.

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration, but most of the films it showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

The Corridor

This science fiction/horror story follows a group of old high school friends, drifting apart from one another, as they reunite for a weekend of bonding at an isolated cabin in the middle of winter. Here they make contact with an otherworldly force, and are unprepared for the indelible changes it leaves on their psyches. As the strange force’s influence grows, the friends find their sanity stretched beyond the breaking point and their lives in peril.

Indie Horror Done Right, the Canadian Way

The Corridor is one of those films that I wish was made more often. It reaches beyond its budget, is well written, and makes a unique interpretation of a classic trope (the cabin in the woods) by adding a genuinely Canadian voice to the genre. That’s high praise, and The Corridor deserves it.

It’s an annoying stereotype to call Canada the ‘great white north’; however, the isolation of the north is something that holds a special place in the Canadian psyche (even a Toronto boy like me knows a few lines from Robert Service’s The Cremation of Sam McGee by heart). The Corridor does a great job of capturing that feeling on film – the sense of being trapped, the cold, and the peculiar way the snow seems to absorb sound. During the Q&A after the screening, director Evan Kelly admitted what a pain it was to shoot in the snow (once you’ve kicked through a snow bank, you can’t exactly reset the scene), but I’m glad they were ambitious enough to try on the limited budget the film had, because it paid off. Visually, it sets an appropriate tone for the film, with all that oppressive whiteness pressing in on the landscape and squashing the characters. Plus, the winter is a natural obstacle to the characters simply walking away from their problems, so The Corridor avoids some of the suspension of disbelief problems that a lot of cabin in the woods movies are burdened with.

I think that The Corridor’s ‘Canadian-ness’ goes beyond its wintry setting to the nature of the fear it explores. While most (American) cabin in the woods films (like Cabin Fever, or even, if the concept of isolation is stretched, The Divide) deal with the disintegration of groups into fractured, lone individuals, the alien force in The Corridor represents overwhelming integration into a group that violently overwrites the self. I think the argument can be made that a country’s national values also hold their secret fears, and if individualism is an American ideal/fear, then I think that you can say that collectivism is our Canadian ideal/fear.

Even though it takes a while for the blood to start flowing, Kelly avoids boredom by slowly turning up the tension between the characters. While most of us don’t have to deal with mental illness in our circle of friends (another credit to the movie is the deft hand with which schizophrenic Tyler is portrayed), the grudges, hurt feelings, and lines of alliance between the characters is something that we can all relate too (especially with a group of people who grew up together). It all works to make the characters believable, which gives the violence all the more impact when it explodes onto the screen (and there’s a couple of pretty gruesome scenes in there).

Watching The Corridor reminded me of the first half of Dreamcatcher, before it takes a left turn and Morgan Freeman starts chewing on the scenery (he wasn’t the worst culprit, but he was the most unexpected one), but that doesn’t really do The Corridor justice. I think a better comparison is to H.P. Lovecraft’s short story, The Colour Out of Space. The Corridor doesn’t have any forbidden colors (or any of the trappings of the Cthulhu mythos), but the portrayal of something truly ‘other’, and the madness that force invokes, has a very Lovecraftian feel. Portraying the ‘unknowable’ is even harder on the screen than it is on the page, but I was impressed with the route that The Corridor took, walking a tight line between explaining too much and leaving things so vague as to be meaningless. By the end I felt very satisfied with the story, and although screenwriter Josh MacDonald revealed in the Q&A that this was an aspect of the film he labored over, I never once felt the mystery was disingenuous or sloppy (as I’ve said before, two of my writing pet-peeves).

There were a few scenes where I thought the acting could use a little more punch, but in general the performances were good. Likewise, there were elements that could have been more polished (for example, the character Bobcat, who was supposed to be bald, had pretty visible stubble on his head for a lot of the film), but honestly those are things that I would have completely overlooked in a lesser film. I only looked for perfection because The Corridor set the bar so high.

The Corridor is highly recommended; watch it to see what Lovecraft might look like completely removed from all the Yog-Sothothery.

RPG Goodness