These It Came from the DVR articles are going to be a little bit different. As an early Christmas present to myself, I picked up a festival pass to the Toronto After Dark film festival. So the first difference is that these are new movies, on the big screen, instead of old ones and niche programming on the small screen. The second difference is that these are going to be short. I’ve got eighteen films to see in seven days (as well as dressing up for the annual zombie walk), so I’m not going to have a whole lot of time to write, and I want post these while the blood is still fresh.

Toronto After Dark is a horror and genre film festival oozing with gobs of monster and rpg inspiration, but most of the films it showcases won’t see wide release – so in addition to extracting some rpg goodness from each movie, I’ll also give them a bit of a critique, so fellow gamers can know what they need to track down and what to avoid. I’ll try and keep spoilers to an absolute minimum.

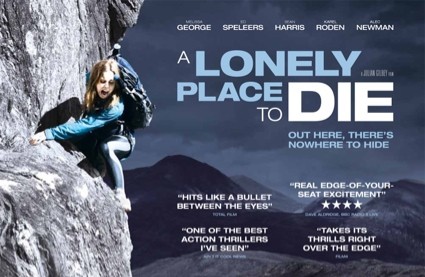

A Lonely Place to Die

In this nail-biting thriller, Allison brings her new boyfriend on a mountaineering adventure to meet her three climbing partners and tackle a challenging peak in the Scottish highlands. There they stumble upon a small girl buried alive in a makeshift prison and attract the attention of a group of murderous criminals who will stop at nothing to get her back. All that stands between the mountaineers and escape from their pursuers are the highland’s raging rapids, bone shattering falls, and impassable chasms

Grabs Hold of You like an Angry Rottweiler

A Lonely Place to Die is one hell of an intense film, and does for rock-climbing what The Descent did for caving (although seeing as I’m afraid of heights and don’t like confined spaces the likelihood that I would have tried either, even before seeing the films, is pretty slim). The Gilbey brothers don’t waste a lot of time on bloated backstories, giving the audience just enough that they care about the characters and understand the group dynamics. The film gets to the set-up fast, and as soon as the mountain climbers find the kidnapped girl, the unrelenting action begins.

I’m not kidding when I say ‘unrelenting’. In most action/thrillers the tension tends to come in waves – there’s a chase scene, and then a rest; they’re caught again, and then they get away (The Bourne Identity is a good example of this format). This is not how A Lonely Place to Die works. Once the chase down the mountain begins, it’s cranked up to 10 until the credits roll. No one gets a break – not the characters, and certainly not the fool in the theatre who ordered the biggest drink and has to go to the bathroom (thankfully that wasn’t me). The sheer energy that drives this film forward is what makes it work. Like the characters fighting for their lives, there is no time to stop and think, and possibly question the actions of the film’s villains, because the camera is now hung out over a dizzying ledge and we’re too busy worrying the protagonist might not make that jump. But honestly, who cares about the plot when the Gilbey brothers have set out a clear goal (make it off the mountain with the girl alive), and keep us on the edge of our seats, biting our nails over what’s at stake (and what action/thriller doesn’t have some silly plot elements?).

A Lonely Place to Die uses violence in a way that mirrors and complements the pacing. It’s unglamorous, brutal, and before you can deal with it, the film moves on. It does an excellent job of putting the viewer right in the middle of the frantic scramble for survival, which is exactly what you want from an action/thriller.

The movie draws obvious comparisons to Cliffhanger, only A Lonely Place to Die takes a handful of Cliffhangers, boils down the best parts and distills the mix until its 100-proof. Where Cliffhanger is (fun, but) overproduced, the Gilbey brothers and the cast spent a few weeks learning how to rock climb so they could film right on the side of the mountain and do the stunt work themselves. The directness of this kind of filmmaking infuses A Lonely Place to Die not only with believable action scenes, but also some breathtaking vistas of the Scottish highlands that would have been impossible to achieve (or cost prohibitive) with traditional filming techniques.

Unfortunately, given how strong the first three-quarters of the film are, A Lonely Place to Die trips up a little near the end. I don’t want to spoil anything (see below), but it almost seems as if the Gilbey brothers forgot why the bulk of the film is so awesome.

Overall, A Lonely Place to Die is recommended, especially if you want to see a raw version of Cliffhanger without the cheese. Watch it to snap you out of mid-season television and get your heart pumping again.

SPOILER

There were two things I want to comment on, but they are definitely spoilers.

First, I really love how the Gilbey brothers establish early on in the film (in a spectacularly unexpected death that will snap you out of complacency Tropic Thunder and Deep Blue Sea style) that absolutely no character is safe. This was an incredible tool for amping up the tension, as I genuinely thought that any of the characters could go at any second (and with a child involved, that’s a pretty heavy threat).

Second, I’ll explain my criticism a little more. Once the protagonists leave the mountain, the film loses the singular focus that drove the narrative forward so strongly. I appreciate the filmmakers playing with my expectations on an intellectual level, but this film is all about visceral engagement, so I have to call the last quarter of the film a failed experiment.

RPG Goodness

A Lonely Place to Die is a fantastic resource for rpg players. Besides being the perfect film to use as research for an alpine adventure (or just to get amped up before a game session), there are elements of the film that wouldn’t be out of place in a session of D&D. See if this basic plot sounds familiar:

A group of people band together (some of whom know each other and some of whom don’t) to go on an adventure. Along the way they stumble upon a prisoner and decide to take up the quest to bring her back to the safety of civilization. With limited resources they must navigate their way through a dangerous environment and fend off attacks from the villains who captured the prisoner in the first place. Cue death and mayhem.

Sounds like your average game session, doesn’t it? Thinking about A Lonely Place to Die (and reading Blog of Holding’s latest post about the ‘star labyrinth’), made me rethink my notions of overland travel and wilderness encounters in D&D (I’ve always been more interested in urban and dungeon settings). There is a tendency to view the wilderness as a two dimensional plane, where the characters can travel anywhere they please (I think D&D’s, and my own, fetishization of mapping encourages this, as does the venerable hex-map) with a die roll to avoid getting lost, but the world off the road is as full of ‘walls’ as any dungeon. The main difference between the wilderness and the dungeon is that every party has at least one member highly skilled at climbing (or swimming) or with access to some terrain avoiding magic (like levitation or fly); so, instead of a wilderness adventure’s walls being restrictions, they are highly advised suggestions. Rather than directing travel, a wilderness corridor funnels it (not everyone is going to want to scale that cliff or swim across that river). This makes the wilderness ‘dungeon’ especially well-suited to a dynamic adventure where the choices of the players have a huge impact on the actions of the monsters (which is pretty much how it plays out in the film). A map can still provide areas with location based encounters, only the players have more control over which route they take and how they get there (weighing the danger of the terrain against a shortcut or an avoided encounter). This means that DMs are going to have to do a little extra work in determining how the monsters will react to the PCs (and the PCs’ movement through the territory), but is the perfect opportunity to throw in some of those creatures whose Monster Manual description has them using hit and run or stalking tactics that are rarely ever replicated in actual table top play (like displacer beasts, doppelgangers, and minotaur).

As an experiment I would love to transform a classic dungeon map into a wilderness adventure using the ideas I’ve mentioned, but that is something that will have to wait for a future blog post.

Tags: Blather, D&D, Pop Culture, System Neutral